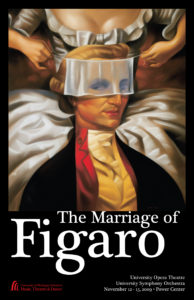

The Marriage of Figaro

Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Lyrics by Lorenzo da Ponte

Based on the comedy by Pierre Beaumarchais

University Opera Theatre • University Symphony Orchestra

November 12-15, 2009 • Power Center

The Story: Count Almaviva’s valet Figaro is looking forward to his imminent wedding with the beautiful Susanna. Unfortunately, his lascivious employer is also intent on bedding the young chambermaid. Aware of the Count’s intentions, the Countess, with Susanna’s help, intends to teach her husband a lesson on the dangers of infidelity. Add in a love-sick teenager who causes unexpected confusion and hilarity abounds as multiple love interests vie for the perfect pairing. Through subtle intrigue, scintillating sexual games, and mistaken identities, Figaro and Susanna must outmaneuver and outwit the entire household to end up finally in each other’s arms.

Artistic Significance: Called “the world’s most perfect opera,” The Marriage of Figaro has delighted audiences since its premiere in 1786. The first collaboration between Mozart and librettist da Ponte, Figaro is the successful sequel to The Barber of Seville. Da Ponte’s witty libretto melds humor with humanity and is paired with Mozart’s groundbreaking score in a true marriage of music and drama. From the instantly recognizable overture to the rousing ensemble finale, the opera is filled with one brilliant melody after another. A celebrated operatic tour de force, The Marriage of Figaro sparkles with genius.

Artistic Staff

Director: Robert Swedberg

Conductor: Kenneth Kiesler

Assistant Conductor: Oriol Sans

Scenic Designer: Peter Harrison

Costume Designer: Christianne Myers

Lighting Designer: Craig Kidwell

Wig Designer: Erin Kennedy Lunsford

Diction Coach: Timothy Cheek

Chorus Master: Reed Criddle

Repetiteurs: Matthew Brower, Ana Otamendi

Stage Manager: Mitchell B. Hodges

Cast (Thursday-Saturday/Friday-Sunday)

Figaro: Jonathan Christopher/Edward Hanlon

Susanna: Mary Martin/Nicole Greenidge

Countess: Rhea Olivaccé/Theresa Bridges

Count: Joseph Roberts/Jesse Enderle

Cherubino: Kate Wakefield/Monica Sciaky

Marcellina: Kristin Eder/Monique Holmes

Bartolo: Benjamin Sieverding/Nicholas Ward

Basilio: Kyle Matthew Knapp/Willis Berne D. Bote

Barbarina: Jennifer Gordon/Stephanie Hradsky

Antonio: Drew Smith/Austin Chrzanowski

Ensemble: Camila Ballario, Leah Bobbey, Ben Brady, Andrew Catalano, Kathryn Graham, Matthew Greenblatt, Robert Harris, Kelly Hedgspeth, Austin Hoeltzel, Michael Martin, Alan Nagel, Amanda O’Toole, Sarah Ring, Kristen Seikaly, Kate Spear, Nathan Taylor, Carol Urban, Jeffrey Wilkinson, Jeremy Williams, Samantha Winter, Sara Zeglevski

Understudies

Figaro: Josh Sanchez

Susanna: Kimberlin Bolton

Countess: Claire DiVizio

Count: Glenn Ellington

Cherubino: Emily Goodwin

Sponsors

The School of Music, Theatre & Dance acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Media Sponsorship by WRCJ.

Resources

[accordion title=”Synopsis”]

Act I

A country estate outside Seville, late eighteenth century. While preparing for their wedding, the valet Figaro learns from the maid Susanna that their philandering employer, Count Almaviva, has designs on her. At this the servant vows to outwit his master. Before long the scheming Bartolo encounters his housekeeper, Marcellina, who wants Figaro to marry her to cancel a debt he cannot pay. After Marcellina and Susanna trade insults, the amorous page Cherubino arrives, reveling in his infatuation with all women. He hides when the Count enters the servants quarters. The Count furious because he caught Cherubino flirting with Barbarina, the gardener’s daughter. He pursues Susanna but conceals himself when the gossiping music master Don Basilio approaches. The Count steps forward, however, when Basilio suggests that Cherubino has a crush on the Countess. Almaviva is enraged further when he discovers Cherubino in the room. Figaro returns with fellow servants, who praise the Count’s progressive reform in abolishing the droit du seigneur – the right of a noble to take a manservant’s place on his wedding night. Almaviva assigns Cherubino to his regiment in Seville and leaves Figaro to cheer up the unhappy adolescent.

Act II

In her boudoir, the Countess laments her husband’s waning love but plots to chasten him, encouraged by Figaro and Susanna. They will send Cherubino, disguised as Susanna, to a romantic assignation with the Count. Cherubino, smitten with the Countess, appears, and the two women begin to dress the page for his farcical rendezvous. While Susanna goes out to find a ribbon, the Count knocks at the door, furious to find it locked. Cherubino quickly hides in a closet, and the Countess admits her husband, who, when he hears a noise, is skeptical of her story that Susanna is inside the wardrobe. He takes his wife to fetch some tools with which to force the closet door. Meanwhile, Susanna, having observed everything from behind a screen, helps Cherubino out a window, then takes his place in the closet. Both Count and Countess are amazed to find her there. All seems well until the gardener, Antonio, storms in with crushed flowers from a flower bed below the window. Figaro, who has run in to announce that the wedding is ready, pretends it was he who jumped from the window, faking a sprained ankle. Marcellina, Bartolo and Basilio burst into the room waving a court summons for Figaro, which delights the Count, as this gives him an excuse to delay the wedding.

Act III

Susanna leads the Count on with promises of a rendezvous in the garden. The nobleman, however, grows doubtful when he spies her conspiring with Figaro; he vows revenge. Finding a quiet moment, the Countess recalls her past happiness. Marcellina is astonished but thrilled to discover that Figaro is in fact her longlost natural son by Bartolo. Mother and son embrace, provoking Susanna’s anger until she too learns the truth. The Countess enlists the aid of Susanna in composing a letter that invites the Count to the garden that night. Later, during the marriage ceremony of Figaro and Susanna, the bride manages to slip the note, sealed with a hatpin, to the Count, who pricks his finger, dropping the pin, which Figaro observes.

Act IV

Barbarina, after unsuccessfully trying to find the lost hatpin, tells Figaro and Marcellina about the coming assignation between the Count and Susanna. In the moonlit garden, Susanna and the Countess are ready for their masquerade. Alone, Susanna rhapsodizes on her love for Figaro, but he, overhearing, thinks she means the Count. Figaro inveighs against women. Susanna hides in time to see Cherubino woo the Countess – now disguised in Susanna’s dress – until Almaviva chases him away and sends his wife, who he thinks is Susanna, to an arbor, to which he follows. By now Figaro understands the joke and, joining the fun, makes exaggerated love to Susanna in her Countess disguise. The Count returns, seeing, or so he thinks, Figaro with his wife. Outraged, he calls everyone to witness his judgment, but now the real Countess appears and reveals the ruse. Grasping the truth at last, the Count begs her pardon. All are reunited, and so ends this “mad day” at the court of the Almavivas.

— courtesy of Opera News

[/accordion][accordion title=”From the Director”]

When French playwright Pierre-Augustin de Beaumarchais wrote his play “le Mariage de Figaro,” he had set out to make a strong political statement about the inequities between the wealthy ruling aristocracy and everyone else. He chose to make his point with the concept of “le droit du seigneur” – or the long-standing tradition of the lord of the manor having the right to share the bed of his peasants’ newlywed brides on their wedding nights. Beaumarchais used that device to demonstrate the absurd inequalities that had developed between the classes over the centuries, and hoped to show that in the new “age of enlightenment” blossoming at the end of the eighteenth century, such customs should no longer be tolerated. But by letting the crafty servant Figaro triumph over his master, Beaumarchais was playing with fire, and when Da Ponte and Mozart set the play to music in Le Nozze di Figaro, they too were fanning flames that would soon burst into a great conflagration. Just five years after the premiere of the opera, aristocratic heads would roll in the Place du Concorde in Paris, signaling the end of the absolute power of the wealthy aristocracy. Or did it?

Audiences viewing Le Nozze di Figaro for the first time in 1786 must have felt the palpable pulse of the revolution growing around them, which must also have given the opera teeth that made it even more meaningful to them. Seen from the perspective of 2009, it may be difficult to imagine the depth of the passions and provocations that led to such bloody massacre and violent change in the era of the premiere. Today, when we experience Le Nozze di Figaro do we now view those elements as interesting, even charming fixtures of a bygone era? Perhaps we should be satisfied that the opera contains some of the most divine music ever written, and enjoy it benignly as a museum piece. Or, perhaps there are contemporary parallels that can be drawn to modern situations that should make us as passionate as our eighteenth century brothers and sisters of the revolution.

What might Count Almaviva’s “droit du seigneur” be today? Perhaps it is the presumed right of the corporate aristocracy to have its way with the environment or the excess of corporate bonuses. Can we be as clever and responsible as Figaro in helping to change these situations? Who is Basilio today? Perhaps the 18th century purveyor of gossip and intrigue is best seen now in terms of mass-marketing and the unwieldy power of the press. Twenty-first century pop-culture versions of Cherubino and Barbarina are on every street, in every city, counter-balanced by the crotchety conservatism of modern versions of Bartolo and Marcellina.

But what Mozart knew better than Beaumarchais is that this piece is really more about love than revolution. Figaro and Susanna show the kind of beautiful, deeply felt love that is worth fighting for. Cherubino and Barbarina show the wonders of love at its most hormonal awakening. Bartolo and Marcellina eventually find the mature love that grows from pride in progeny. And perhaps the most noble love comes from a Countess who has the ability to see the bigger picture and can forgive the philandering nature of a husband who must really love her very much as well. So, there is plenty to think about and to feel, as we celebrate this revolutionary music of love and the timeless genius of Mozart.

— Robert Swedberg

[/accordion]

Media

Program

Photos

[cycloneslider id=”09-10-marriage-of-figaro”]