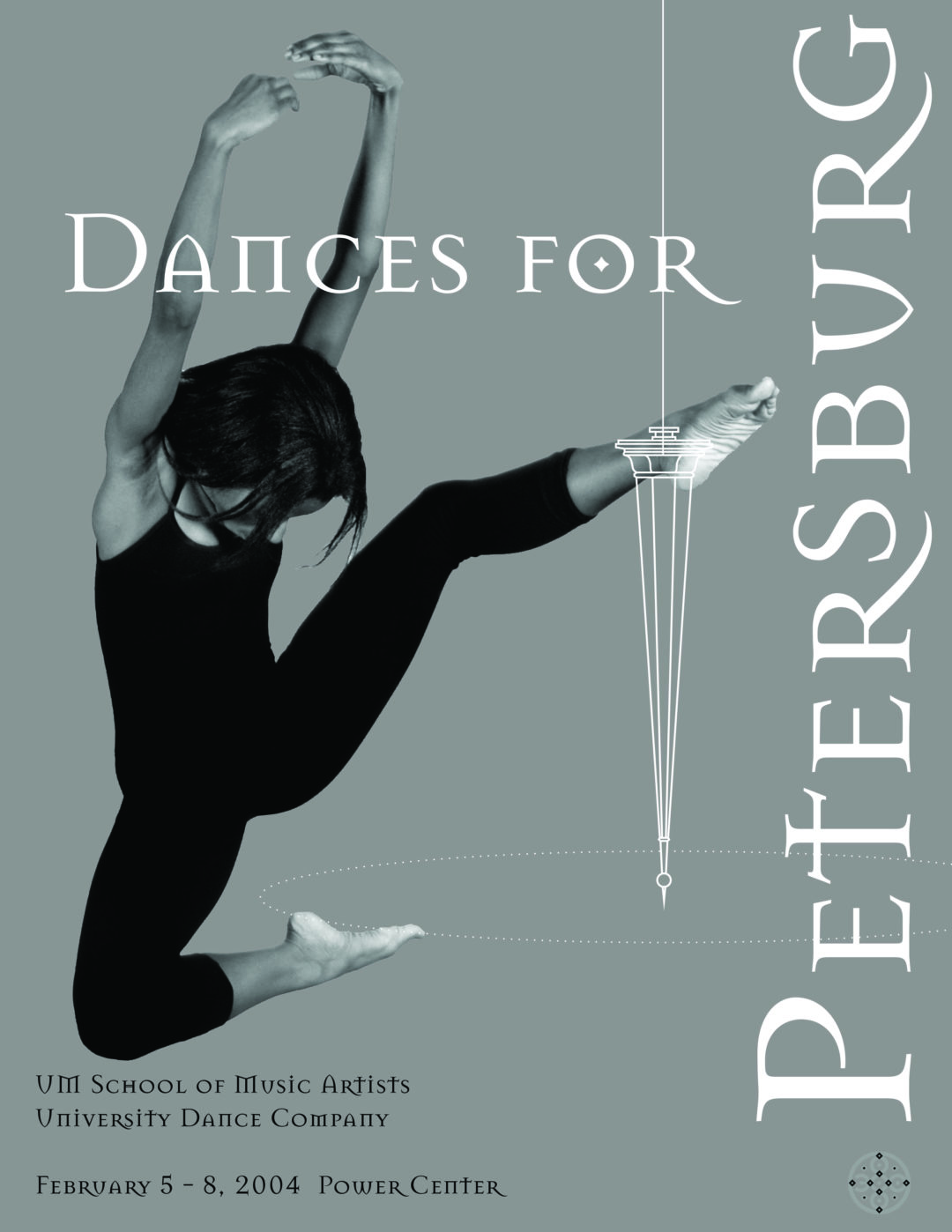

Dances for Petersburg

Choreography by guest artist Alonzo King and faculty Gay Delanghe, Bill De Young, Jessica Fogel, Ruth Leney-Midkiff, and Peter Sparling

Department of Dance

February 5-8, 2004 • Power Center

Featuring choreography by guest artist Alonzo King and faculty members, “Dances for Petersburg” is an evening of modern dance set to music of Russian composers as part of the University-wide “Celebrating St. Petersburg” festival. The concert will feature live music by a variety of School of Music student performers under the musical direction of Jonathan Shames.

Artistic Staff

Artistic Director: Bill De Young

Scenic & Costume Designer: Jeff Bauer

Lighting Designers: Mary Cole, Michelle Epel Sherry

Musical Direction: Jonathan Shames

Stage Manager: Amanda Heuermann

Repertoire & Performers

[accordion title=”Trumpet Fanfare”]

Music: “Fanfare for a New Theatre” by Igor Stravinsky

[/accordion][accordion title=”La Duncan and Fokine”]

Choreography by Gay Delanghe

Music: ““Souvenir de Hapsal, Op. 2 – #3 Chant sans paroles”” and “Valse Caprice, Op. 4” by Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky

Piano: Angela Yun-Yin Wu

Dancers, Part I: Julia Billings, Kathleen Michelle Boyer, Raija Gershberg, Jennifer Seguin

Dancers, Part II: Julia Billings, Kathleen Michelle Boyer, Alexandra Burley, Stephanie Calandro, Nicolle Cooper, Jenny De Muth, Sarah Ash Evens, Joyelle Fobbs, Raija Gershberg, Maureen Kelley, Lizzie Leopold, Elizabeth Maderal, Jenny Schulz, Jennifer Seguin, Heather Vaughan-Southard, Katherine Zeitvogel

Choreographer’s Notes: This work is based on the effect of modern-dance pioneer Isadora Duncan’s performance in St. Petersburg in 1904, which is also the year of birth of great Russian-American-modern-ballet choreographer George Balanchine. The Russians thought Duncan an amateur and whenever they saw dancing that was bad or poor in taste, they would state “C’est La Duncan.” However this dance explores the influence of Duncan’s movement on Russian ballet choreographer Michel Fokine, who is considered the father of modern ballet. Fokine choreographed Les Sylphides, his first break from conventional structure, in 1909 after viewing Duncan in 1904. So the timeline is skewed in La Duncan and Fokine. But the dance brings forward Fokine’s reforms of freeing the ballet of the time from some of its limitations, a mix of classical and character dance, lack of dramatic logic or atmosphere, bravura for the sake of applause and use of music written only for dance, by utilizing Duncan’s point of view for creating choreography. The dance includes movement quotes from both Duncan’s dances and Fokine’s Les Sylphides.

[/accordion][accordion title=”Sonata for Alto Sax and Piano”]

Choreography by Bill De Young

Music: “Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano, Op. 37 (3rd movement – Allegro Moderato)” by Edison Denisov

Saxophone: Brian Sacawa

Piano: Kathryn Goodson

Dancers: Libby Allsberry, Shannyn Hart, Natalie Lacuesta, Christine Naughton Shawl, Heather Vaughan-Southard

[/accordion][accordion title=”The Second Space”]

Choreography by Peter Sparling

Music: “Symphonies of Wind Instruments” by Igor Stravinsky

Set design inspired by the paintings of Kazimir Malevich: “Peasant Woman” (1930) and “Yellow Quadrilateral on White” (1916-17)

Dancers: Sara Badger, Shawn T. Bible, Melissa Bloch, Anna Bratton, Lauren DuCharme, Jon Frederick, Jenna Giorgio, Stacie Greskowiak, Natalie Griffith, Justin House, David Knapp, Yael Lubarr, Dominique Melissinos, Jordan Newmark, Amanda Christine Roundtree, Elizabeth A. Schmuhl, Molly M. Schneider, Christine Naughton Shawl, Cara Steen, Jessica Vartanian, Jenna Lane Walters, Leslie E. Williams, Susannah Windell

Choreographer’s Notes: “The Second Space” takes its name from a poem of the same title by the Polish poet, Czeslaw Milosz. The poet pleads for a return to the imagery of faith: “The heavenly halls are so spacious!/ Ascend to them on stairs of air./ Above white clouds the hanging celestial gardens.” “A soul tears away from the body and soars./ It remembers that there’s up and down.” “Let us implore, so that it is returned to us,/ The second space.” Stravinsky described his score as “austere ritual.” It suggests to me a meeting ground upon which a community moves towards a collective ideal. The first three-fourths of the work features a series of episodes punctuated with a recurring and insistent thematic “proclamation.” Against these elements, a chorale-like passage inserts itself until it overwhelms the work for the final section of transcendent sonority, i.e. “the second space.” This strikes me as parallel with the philosophy and imagery of the Russian artist, Kazimir Malevich, (1878-1935), whose Suprematist vision departed from the Cubists or Constructivists – in opposition to any combination of art with utility, technology or imitation of nature. His aim was a pure art that transcended religion or politics, and his own non-objective art was radical for its time, prefiguring the minimalism of the later 20th century. He introduced his stark, geometric paintings at “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd in 1915, issuing his manifesto for “pure-painting composition”: “Things have disappeared like smoke before the new art culture. Art is moving towards its self-appointed end of creation, to the domination of the forms of nature.”

[/accordion][accordion title=”Point of No Return”]

Choreography by Ruth Leney-Midkiff

Music: “Étude, Op. 2” and Sonata #7 in B-flat major” by Sergei Prokofiev

Piano: Ming-Hsiu Yen

Projections: Jennifer Seguin

Dancers: Alexandra Burley, Stephanie Calandro, Nicole C. Jamieson, Maureen Kelley, Natalie Lacuesta, Leslie Alexandra Murchie, Ryan L. Myers, Christy L. Thomas, Katherine Zeitvogel

I. Perilous Leap

II. Lucent Plunge

III. Quantum State

IV. Feverish Insomnia

Choreographer’s Notes: Point of No Return is inspired by the work of Rayonist painters Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova (1913-15). Drawing upon the innovations of the time – theories of light, the celebration of speed and dynamism, and the exploration of abstraction – the rayonists sought to depict the intangible spaces inbetween objects as the “ceaseless and intense” intersection of rays of light bouncing off tangible forms. In presenting a visual articulation of these spaces inbetween, the artists attempted to depict the “fourth dimension.” I have taken inspiration for each movement based upon my readings and have sought to capture the beauty of speed, the darting interplay of diagonal lines, and the athleticism that takes the performer into that intangible space of light in-between. Special thanks to Andrew Midkiff.

[/accordion][accordion title=”Shostakovich String Quartet”]

Choreography Alonzo King

Staged by Summer Lee Rhatigan

Rehearsal direction by Judy Rice

Original Costume Design by Robert Rosenwasser

Music: “String Quartet #15 in E-flat minor, Op. 144” by Dmitri Shostakovich

Rosseels Graduate Quartet: Martha Walvoord (violin), Bethany Mennemeyer (violin),

Elvis Chan (viola), Noella Yan (cello)

Dancers, Thursday/Saturday

Part I: Kathleen Michelle Boyer (soloist), Libby Allsberry, Shannyn Hart

Part II: Leslie Lamberson

Part III – Pas de Deux: Roche Janken, Brian McSween

Part IV: Libby Allsberry, Kathleen Michelle Boyer, Raija Gershberg, Jenna Giorgio, Shannyn Hart, Leslie Lamberson

Dancers, Friday/Sunday

Part I: Raija Gershberg (soloist), Torrie M. Hoffmeyer, Leah Ives

Part II: Joyelle Fobbs

Part III – Pas de Deux: Leslie Lamberson, Brian McSween

Part IV: Julia Billings, Melissa Bloch, Joyelle Fobbs, Roche Janken, Torrie M. Hoffmeyer, Leah Ives

[/accordion][accordion title=”We Will Meet Again In Petersburg”]

Choreography by Jessica Fogel

Poems by Osip Mandelstam

English translation by Ephim Fogel

Russian Recording: Oleg Redkin

Video Editor: Jennifer Seguin

Photoshop Editor: Shawn T. Bible

Narrator/Poet: Leigh Woods

Dancers: Shawn T. Bible, Alexandra Burley, Daytona Frey, Natalie Griffith, Matthew Hakim, Kyle Marie Herrala, Leah Ives, Roche Janken, Lizzie Leopold, Mudhillun K. MuQaribu, Jordan Newmark, Ross Oliver, Jessica Sachs, Kristen Sague, Molly M. Schneider, Jennifer Seguin, Christy L. Thomas, Melanie Anastacia Van Allen

I. Brother to water and sky

Poem: “The Admiralty” (1913) Music: “Piano Quintet in G Minor, Op. 57 (Scherzo)” by Dmitri Shostakovich

Musicians: Angela Yun-Yin Wu (piano), Martha Walvoord (violin), Bethany Mennemeyer (violin), Daniel McCarthy (viola), Christopher Wild (cello),

II. At a terrible height

Poem: #101 (1918) Music: “Warlich, ich sage dir: Heute wirst du mit mir im Paradiese sein”

(Verily I say unto thee: Today thou shalt be with me in Paradise) from Seven Words by Sofia Gubaidulina

III. Again

Poem: #118 (1920, revised 1928)

Music Collage: “Vieni a’ regni del riposto” from Orfeo ed Euridice by Christoph Willibald Gluck

Collage engineers: Brendan Kirwin, Greg Laman, Christian Matjias

Choreographer’s Notes: This dance is set to three poems by Osip Mandelstam, one of Russia’s greatest and most influential poets, written during the turbulent years of 1913-1920. Born in 1891, Mandelstam grew up in St. Petersburg and died in the Gulag Archipelago near Vladivostock on December 27, 1938. The dance begins with Mandelstam’s 1913 poem, “The Admiralty,” which celebrates the creative spirit of man as manifest in The Admiralty Building. This building, revered by the residents St. Petersburg as part of their rich architectural and historical heritage, was built in 1704 during the reign of Peter the Great. In the second movement, the dance evokes a poem written in 1918, (#101, “At a terrible height”). This poem is a dark twin of “The Admiralty” and evokes the disintegration of the city and Mandelstam’s sense of despair. The final section of the dance is based on Mandelstam’s 1920 poem #118, “We will meet again in Petersburg.” The poem articulates a hope for the rebirth of old world culture, and the ascendancy of love, art and beauty over war, chaos and totalitarianism.

[/accordion]

Sponsors

The School of Music acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Dances for Petersburg is supported in part by a grant from the National College Choreography Initiative Foundation, a leadership initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts with additional support by the Dana Foundation and is administered by Dance/USA, the national service organization for professional dance.

Resources

[accordion title=”Celebrating St. Petersburg”]

The history of St. Petersburg is an extraordinary tale of arts transforming and arts transformed. Founded by Peter the Great 300 years ago, the glorious city redefined Russia’s idea of itself. St. Petersburg, with its architectural splendor and its magnificent public institutions, embodies the ambition of Peter’s vision to forge a new national identity. Included in the tale of St. Petersburg is its transforming power on the West. Artists of genius, inspired by St. Petersburg, infused visual arts, music, dance, and theater with a Russian flavor that fundamentally changed the face of Western and world arts. “Celebrating St. Petersburg: 300 Years of Cultural Brilliance” includes more than 60 free and ticketed cultural and educational events by the University of Michigan Museum of Art, the University Musical Society, the Center for Russian and East European Studies, the University of Michigan School of Music, and University Libraries.

[/accordion][accordion title=”The Poems”]

The Second Space

The heavenly halls are so spacious!

Ascend to them on stairs of air.

Above white clouds the hanging celestial gardens.

A soul tears away from the body and soars.

It remembers that there’s up and down.

Have we really lost faith in a second space?

They’ve dissolved, disappeared, both Heaven and Hell?

Without unearthly meadows how will one meet salvation?

Where will the gathering of the damned find its abode?

Let us weep, lament the enormous loss.

Let us smear our faces with coal, disarrange our hair.

Let us implore, so that it is returned to us,

The second space.

— Czeslaw Milosz

Translated from the Polish by Robert Hass & Renata Gorczyski

#48 The Admiralty

In the northern capital a dusty poplar pines,

Transparent, a clockface is tangled in its leaves,

And in the dark greenness a frigate or acropolis

Shines from afar, brother to water and sky.

Aerial argosy and touch-me-not mast,

Serving as rule and line for Peter’s adoptive sons,

It teaches: beauty is not a demigod’s whim,

But the raptor’s eyespan of a plain carpenter.

We’re under the genial sway of four elements,

But free man originated a fifth.

Doesn’t it deny the supremacy of space,

This chastely architectured ark?

Capricious medusas cling angrily,

Anchors are rusting, like abandoned plows;

And now the bonds of three dimensions burst,

And the seas of all the world open.

— Osip Mandelstam, 1913

Translated by Ephim Fogel, ©1990

#101

At a terrible height, a wandering fire,

But is that the way a star glimmers?

Transparent star, wandering fire,

Your brother, Pétropol, is dying.

At a terrible height earthly dreams blaze,

A green star glimmers.

The Poems

O, if you are a star,—the brother of water and sky,

Your brother, Pétropol, is dying.

A monstrous ship at a terrible height

Is tearing past, its wings extended.

Green star, in beautiful poverty

Your brother, Pétropol, is dying.

Transparent spring has shattered above the black Neva.

The wax of immortality melts.

O, if you are a star—your city, Pétropol,

Your brother, Pétropol, is dying.

— Osip Mandelstam, 1918

Translated by Ephim Fogel, ©1990

#118

We will meet again in Petersburg

As if we had buried the sun in it,

And for the first time we’ll pronounce

The blessed, meaningless word.

In the black velvet of the January night,

In the velvet of the world’s emptiness,

Still the dear eyes of blessed women sing,

Deathless flowers still are blossoming.

The capital is arched like a savage cat,

A patrol stands on the bridge,

Only a vicious car tears about in the dark

And like a cuckoo cries and cries.

I don’t need a nighttime pass,

I’m not afraid of sentries:

In the January midnight I will pray

For the blessed, meaningless word.

I hear the theater’s light rustle

And the girlish “Ah’s”—

And a mighty heap of deathless roses

Rests in Cypris’s arms.

We warm ourselves from boredom at a bonfire,

Ages it may be will pass,

And the beloved hands of blessed women

Will gather up the light ash.

Somewhere there are the sweet choirs of Orpheus,

And the dear dark eyes,

And playbill-doves from the upper circle

Fall onto the flowerbeds of stalls.

Well, then, if you will, blow out our candles;

In the black velvet of the world’s emptiness

Still the slanting shoulders of blessed women sing;

You, though, will not notice the midnight sun.

— Osip Mandelstam, November 25, 1920; revised 1928

Adapted from the translation by Ephim Fogel, ©1990

[/accordion][accordion title=”A Collaboration of Music and Dance”]

Russian music from Glinka onwards has always been associated with dance. One has only to think of the famous balletic leaps masquerading as piano chords which open Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto or the elegant and precise machinations of all of Stravinsky’s scores to get a sense that Russians compose kinetically as Italians do vocally. Today’s program showcases a variety of these dance inspirations, Shostakovich and Stravinsky providing our lodestones. Stravinsky, without question the major composer of the 20th century, is represented in two works: his “Fanfare for a New Theatre,” written in 1964 in the U.S. for his colleague and fellow Petersburger George Balanchine, and his “Symphonies of Wind Instruments,” written in 1920 to commemorate Debussy’s death. Tchaikovsky, who was Stravinsky’s favorite forebear and the creator of so much immortal ballet music, leads off the main program. Two early piano works illustrate the Chopin influence on this great artist, the same Chopin who inspires the great ballet Les Sylphides. Prokofiev, Stravinsky’s friend and nemesis at the same time, is represented with four piano works that illustrate definitively the new style which he brought to music – forceful, steely, and yet somehow magically melodic as well. Then to Shostakovich, the great composer of the Soviet regime, who suffered at its hands more than anyone, but whose ultimate triumph was the steady creation of 15 symphonies and 15 string quartets. The great 15th Quartet, one of the composer’s last works, from 1974, gives us a full range of this creator’s emotion, from despair and fright to the most intimate whisperings of humanity. And finally short works by two composers championed by Shostakovich, firstly the strikingly named Edison Denisov, son of Siberia, and an avatar of modern trends – his Saxophone Sonata giving us filtered notions of such cherished Western modes as jazz and atonal writing. And second the fascinating Sofia Gubaidulina, ceaseless explorer of folk styles and instruments and a mystic devoted to the life-changing possibilities of music, both tendencies to be found in her Seven Words.

— Jonathan Shames, Musical Director

[/accordion]