Edited by Brandon Monzon, communications generalist and assistant editor of Michigan Muse

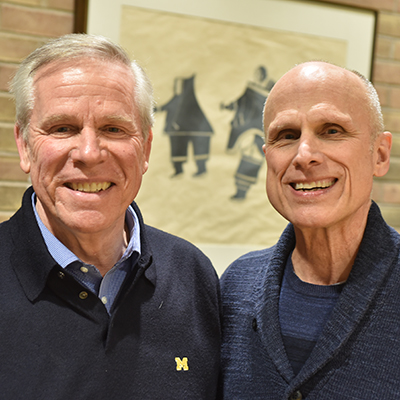

Professors Peter Sparling and Jerry Blackstone reflect on three decades at SMTD as they prepare for retirement.

“I think that in the 30 years I’ve been here, Peter and I have maybe interacted no more than a few minutes,” said Professor Jerry Blackstone, director of choral activities and chair of conducting, as he settled himself at the conference table. “Our worlds are different and separate in terms of locale.”

Peter Sparling, the Rudolf Arnheim Distinguished Professor of Dance, arrived a few moments later and echoed that sentiment. “I’ve had the opportunity to work with composers and instrumentalists because being a choreographer, I’m always hungry for new scores of music. But unfortunately, Jerry’s path and mine didn’t cross.”

Blackstone, a GRAMMY® Award-winning conductor and nationally recognized pedagogue, retires from SMTD this spring after 30 years. While at U-M, he served as director of choirs, conducted the Chamber Choir, was music director of the University Musical Society Choral Union, frequently appeared with the Ann Arbor Symphony, and conducted the Michigan Men’s Glee Club (MMGC) from 1988 to 2002.

Sparling, a former principal dancer with the Martha Graham Company and member of the José Limón Dance Company, is also retiring, after 34 years. The former chair of the Department of Dance, Sparling has performed and staged Graham’s works all over the world, and has extensive experience as an artistic director, choreographer, performer, and dance/arts consultant.

Inspired by The New York Times’s “Table for Three” series, we brought these two legendary professors together to spark a conversation about their expansive and celebrated careers, which, while parallel, rarely overlapped. Over a dinner of takeout Indian food at the Earl V. Moore Building, the pair discussed their SMTD histories, balancing academic and professional careers, upcoming retirement, and more.

MICHIGAN MUSE: Why retirement now?

PETER SPARLING: There’s something about a dancer’s aging body talking to him or her—that has influenced how I navigate my days, how I negotiate how much I can do in the job here. But once I get over the aches and pains, I think it becomes something different. It’s more about feeling that there’s another chapter in my life that has yet to be written.

JERRY BLACKSTONE: I completely understand what you’re saying. There comes a time when you think, “What’s left on the bucket list: pieces to conduct, pieces to prepare? I’ve done most of those pieces.” My dear colleague [former director of bands] Bob Reynolds said to me, “I didn’t retire from music, I just retired from the stuff that goes along with it.” I look forward to the opportunity to make choices as to what to do with my time.

PS: As performers and teachers, it’s always about the next project and your life falls into place, or doesn’t, according to the pressures and the challenges of the next project. What does life look like without that “to do” dictating everything? I’m curious to know what that’s about. The terrifying part of it is that so much of my identity has been forged based on the tasks that I have here, the roles that I’ve played.

JB: My wife keeps reminding me that after I retire, she cannot be my sole source of intellectual stimulation. She said, “You need friends,” and that’s true, because when you come to work, you are surrounded by people all the time.

PS: It is a built-in community.

JB: Absolutely, and I worry a little bit about that, and I will have to be pretty proactive about it. And make sure that the things that I want to do involve interacting with people, because I’m a pretty outgoing kind of guy.

PS: Do you have any idea of how you’re going do that?

JB: It will involve spending some more time with the family, with the grandchildren. I’m still going to guest conduct. I’m still going to be actively teaching in the summers. It’s a new adventure and I’m ready for it.

MM: What would you say is going to be your legacy at SMTD?

PS: Well, [former SMTD dean] Paul Boylan hired me because of my background as a professional dancer in New York. Having worked with Martha Graham, I’m sure he saw that I would bring more prominence to the dance department. I would like to think that I have helped to bring the department into the mainstream of the top dance programs in the country. That I have helped “up” the level of excellence and the expectation of professionalism. And in more recent decades, there’s screendance, this hybrid blending of dance, performance, choreography, and film/video. Eighteen years ago I applied for an interdisciplinary teaching fellowship grant from CRLT with my colleague Terri Sarris from Screen Arts and Cultures. We proposed that we teach an interdisciplinary team-taught course in screendance, and it was accepted. It’s now an important part of the curriculum. Jerry, what do you feel your legacy is going to be?

JB: There are actually three named endowments in my name, so I guess that’s my legacy! There’s a MMGC fund that helps supports overseas touring (the Jerry Blackstone Endowment for International Tours), since that can be a financial burden on the students. And there’s one at UMS to help support performances of major works for choruses and orchestras. And now there’s a new one, just starting, to honor my retirement (The Jerry Blackstone Endowment for Choral Artistry) to provide some discretionary funds for the new director of choral activities.

PS: I’m working now with the development team on an endowment for screendance in my name.

JB: That’s so wonderful!

PS: Did you come to the University with the expectation of getting tenure?

JB: I came without tenure, not knowing if it would happen or not. But Paul [Boylan] said this would be a great platform to develop a career, and he was absolutely right. If you’re at Michigan, then the door is at least cracked. And if you do a decent job, then the opportunities do happen.

PS: I think Paul’s legacy has affected us in that. He really protected the School in terms of central administration. The fact that our culture is so rarefied—and I mean this idea of one student per one private lesson teacher and what that means in terms of tuition and the economics of students. Paul always had to protect that in the name of quality and getting the best students possible to compete against our peers. The fact that he brought dance out of women’s physical education in 1974 was extraordinary.

JB: Yes, and musical theatre and jazz. Those were all things that were added during his tenure, right around the time I came.

PS: Do you feel that you have brought a different way of teaching, a different way of working with students that was unlike the way you were taught?

JB: Students come at what we do from different perspectives and have different expectations. The older I get, the more I expect them to be hungry. One of the things I have loved about being at Michigan, and still love, and that I will miss, is the hungry student. It’s the student who is here to take in everything they possibly can.

PS: I have found that true as well. But I have noticed that this year, for the first time, in the freshman class, I had to work harder than I ever have to keep their attention and keep them focused. They came around, and thank goodness, by this time of year that group is so focused and committed. But there was a moment where I thought, “I have lost it.”

JB: They haven’t experienced that bar, the level of expectations that you have.

PS: They need to be told what the expectations are.

MM: Do you feel that there are more expectations on students today, in terms of having a wider array of skills, such as self-promotion, marketing, et cetera?

JB: I don’t know if there is a wider level of expectations, but there is a wider level of options. The door is wide open for so many possibilities. And sometimes you come to SMTD and you have to narrow that focus to be able to do something really well. Then there has to come a time when you say “Is this really what I want to do for the rest of my life? Are the doors going to be wide enough in that field to support what I want to do and to be creative?”

PS: The options are extraordinary. I would be rather terrified, if I were their age, looking at the world as it is. How does one survive as an artist? How does one use an undergrad degree to find a career? I think students have to be much more clever. The avenues, the pathways aren’t as clear, they’re not as singular and kind of predetermined. They have to use much more of their entrepreneurial attitude. They have to have fewer expectations or assumptions. They can’t assume anything in this world and I think that’s kind of scary.

JB: That’s tricky because that also says you’re not always going to have time to do something really well. Because you need to spread yourself thin enough to do different things.

PS: As dancers, we learn to do everything because we’ve never had it easy. I was always taught that I had to be ready to perform a variety of styles. I had to know how to teach. You had to market yourself and your art. After six years at the Graham company, I decided I wanted to start my own company and I was doing everything from fundraising to lecture demos to finding a lawyer to helping incorporate as a nonprofit. And it has not changed at all in 40 years; it’s still that way. So these are the skills we feel obligated to teach our dancers.

MM: Most performing arts faculty are also performing artists. How have you been able to balance academia and your professional careers?

JB: As a conductor—particularly a choral conductor—in an academic environment, I think it’s a dance, and in the very best and most distressing way! But the older I’ve gotten, the more I feel that I can say, “No, I’m not going to do that. I’m only going to guest conduct the ones that are really interesting.”

PS: We are hired with the expectation we’ll maintain professional careers. In my field, it involves guest performing with outside dance companies and bringing dancers together to do performances. And fortunately, the University has been very generous with me and other choreographers on our faculty. But I think the more important thing is that we stay creatively active and constantly make new work.

JB: There is a sense that you can never do enough, you can never be good enough. That’s more self-imposed than imposed by others around us. But there’s always a sense of “I wish I did that better” or “I wish I knew that.” They are the unfulfilled achievements in the back of your head, and maybe that’s one of the things I’m looking forward to having a little relief from.

PS: That kind of heightened pressure for a higher profile is forever upon us. There’s the myth that once people get tenure, become full professors, they become lazy, and indifferent, and complacent. I’ve rarely ever witnessed that in our School.

JB: That’s a very special thing about Michigan. You’re surrounded with people who are fantastic at what they do and care deeply about doing it well. They care about the students.

PS: It reminds me of coming to Michigan in ’84 and immediately joining with my colleagues, Bill De Young, Gay Delanghe, and Jessica Fogel, to form Ann Arbor Dance Works. We didn’t even think about it. We all knew that we were eager to choreograph, and that we wanted to choreograph for each other. We wanted the luxury and the privilege of working with each other and forming this collective.

MM: How is the dynamic with former students, and the transition that is made from a student-teacher relationship to a collegial relationship?

JB: I love keeping in touch with alumni; they’ll often ask me to come down and work with their choirs. Or they’ll say “My choir is coming through here; would you listen to us?” That’s fantastic; I’m always so pleased when they are doing well.

PS: One of the greatest pleasures and rewards is to see former students taking on positions in major companies or becoming featured as choreographers. Or getting teaching positions and even chair positions in dance departments around the country. That really makes sense of the whole thing.

JB: Yes, it’s fun to be proud of them.

PS: There is nothing more emotional and heartening than to have a tribute from a former student who says “It was in that class when I did that assignment that changed my life. That hooked me to being a choreographer.” And we’ve had our alumni return to work with our students to choreograph works, and that’s been truly meaningful.

MM: Where do you see SMTD and your field going in the next 10 years?

PS:First, a new dance building will change everything. We’ll be closer to our colleagues in theatre, music, composition, and art and design, and be closer to the staff. I think the culture here will change radically.

JB: In the field of choral music there will be a lot of change. People who are really good musicians, who can read very quickly, and instantly adapt their singing, they are getting gigs and are able to make a living. SMTD isn’t a trade school. We’re not just training somebody to get a job, we are training artists: but I think that will change what we do—maybe even how we do it. And I don’t think we can underestimate the influence of a dean, someone with a vision who understands that SMTD is a very special place.

PS: What does 21st-century leadership look like in our school? How does one negotiate with central administration? I’m hoping for a dean who has a certain charisma, but more than that, a really lively intelligence…someone who has been part of a truly interdisciplinary curriculum and programming in various institutions. Someone who has a grasp of multiple disciplines and who knows how to bring them all together and work within a research university.

JB: A dean that allows and enables everyone to flourish. Someone to inspire, to allow people to be creative, and to open doors.

MM: What was the best advice you received in your career and something you’d tell a young professor?

JB: When I came here, I talked to my former doctoral adviser, Rodney Eichenberger, who gave me three bits of advice: Stay out of politics; Do a good job—study, be prepared; and “Be a nice guy and you’ll be successful.” I’d give that same advice to a young faculty member. You can dream at Michigan and you can do anything you want at Michigan. You’re going to work your tail off here. You’re going to work harder here than anywhere. But if you can imagine it, you probably can make it happen.

PS: I would actually move in a somewhat different direction and would say, “Remain politically active but choose your battles.” You have to decide what it is you stand for, and it’s not that you can preach that to your students, but you have to embody it. You have to be a role model and you have to enable that in yourself so that you’re not talking about doing something, you’re doing it. Students want role models. I think we need to be much more mindful of what mentorship means, and I would advise an incoming faculty member to choose his or her battles thoughtfully and to find healthy good mentorship.

JB: Be who you are. That’s always been a challenge for me, but being who you are, and honest and trustworthy—I think that’s pretty important.