By Jennifer DeBord, a freelance writer in Ann Arbor

A father missing his grown son. Two activists facing exhaustion and struggling to find hope. A demolition man from Los Angeles summoned to tear down abandoned houses. A young suburban musician who finds inspiration downtown. And an old-school barber concerned with the influx of hipsters looking for cheap rent.

Residents, scientists, politicians—they all have a voice in José Casas’ new play, Flint.

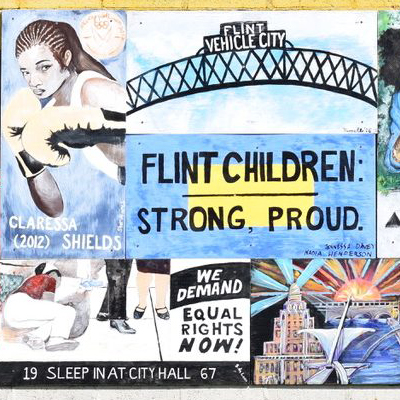

The city of Flint received national attention due to its water crisis—which occurred when the city switched water supplies, exposing its citizens to dangerous levels of lead—but the issues facing Flint predate this disaster. What was once the proud “Vehicle City” has faced economic hardship, high crime, and a shrinking population since General Motors substantially slashed their manufacturing in the area in the 1980s.

Enter José Casas, an assistant professor of theatre & drama since 2016. “When I applied for a job at Michigan, I hadn’t heard of Flint,” he remembered. “As I started to do my own research, I started to get more and more angry—which usually is the genesis of my work to begin with. What solidified it were the stories of people not receiving water because they were forced to show identification of citizenship. That was the moment I decided: if I’m coming to Michigan, I’m doing this play.”

Casas, a native of Los Angeles, is a prominent playwright working primarily in the field of Applied Theatre, which uses non-traditional settings and approaches as well as ethnographic and documentary techniques. “I consider myself an issue-driven writer,” he said. “I’m very much about social justice and telling stories of communities that have been traditionally underserved or marginalized.”

To create Flint, Casas conducted more than 80 individual interviews, building a diverse, complicated, and multilayered modern account of the city. All of the dialogue in the play is taken either from those interviews or the speeches of public officials, scientists, and engineers.

“Some of the people I asked to interview; others I ran into. I met the actress at my gym, the cashier at the Burger King. I really enjoyed those moments where you’re not expecting to find a story and then you find one,” he explained.

While the water crisis is the most pressing issue facing Flint residents today, the play digs past the headlines to plumb the deep range of conflict and emotion that are a part of this city. There are joyous scenes, too; kids dance at prom and an interracial couple tell their love story of missed opportunities and rediscovery. One of the most challenging monologues is the brain-injured actress’s story of thwarted dreams, which is interspersed with brief moments of magical realism.

Distilling a year’s work of interviews down to a tight theatrical piece takes vision, skill, and sensitivity. “Every interview is honest and authentic and respected; my goal is to shape and tell the story in a way that is responsible and not out of context,” explained Casas. “It’s about building a throughline and amplifying to hit the heart of what each particular person was trying to communicate. If you saw my notebooks right now, there are lots of pencil marks and lots of criss-crossing. That’s the process.”

With the play’s premiere by the Department of Theatre & Drama scheduled for April 2019, Dexter Singleton was brought on board to direct. He is a Detroit native and alumnus of Western Michigan University and Mosaic Youth Theatre, and the executive artistic director of Collective Consciousness Theatre in Connecticut.

“Dexter was the first person on my mind,” said Casas. “I knew him through Theatre for Young Audiences, and I wanted a director who was not only going to work with kids, but who used Applied Theatre. I don’t want this to be just another play; I want it to involve students in critical thinking. We talk about bodies as vessels for your craft—your body is a vessel for social activism as well. It was really important to get a director who knew both of these worlds.”

Singleton arrived on campus in late September to conduct a week-long workshop of the piece with a cast and crew of Theatre & Drama students. This is an essential process that gives playwrights the first opportunity to hear their work spoken by actors, with little or no staging. At the end of the week, public readings were held in both Ann Arbor and Flint.

“I knew [Flint] was going to be in raw pieces, so I’ve been looking forward to this, to start pulling layers and see where it takes us,” reflected Casas. “I tell my students that a lot of times, playwriting is really lonely. If you get this opportunity where you are working with the director and actors and dramaturgs, take advantage of that. It is such a wonderful space to be in, because you find things in your play that you never saw, but that come from your collaborators.”

“For many actors, workshops and readings will be a majority of their work; it’s an important process in the professional world,” said Singleton. “As an actor, you are both building relationships with directors and playwrights and then hoping that you can be attached to the project when it becomes a full production.”

While Morgan Waggoner, (BFA ’19, acting) has performed in a variety of productions at U-M—from Shakespeare to Tony Kushner’s Angels in America—she found the experience of workshopping a brand-new adaptive theatre piece simultaneously thrilling and daunting. “On the first day, José and Dexter put the scripts aside and had everyone go around the table and speak about what we knew about Flint. It quickly became a social and political conversation, which made it personal for all of us. This was so unique —I’ve never had a playwright in the room like that.”

Performing the monologues of not only real people, but potential audience members, created its own set of challenges. “It was nerve-racking,” she stated. “You don’t want to get it wrong.”

For previous roles, Waggoner had been able to research characters and previous performances. Casas, however, didn’t let the actors hear his recordings. Instead, he encouraged the students to make artistic choices based on their own character exploration. “Not knowing anything makes you want to retreat and play it safe. That’s the easy thing to do,” noted Waggoner. “But it became clear that these are really important stories about people who have never been given a mic. So you have to lean into it and take risks.”

The audience at the September reading in Flint included several of the people whom Casas had interviewed. “Immediately, when we were done, everyone spoke up. It was so emotional, and that will stick with me for a long time,” recalled Waggoner.

“One of the really interesting things about developing a show about Flint in Ann Arbor is that these are socially, economically, and demographically totally different cities, but they are also close to one another and have the university connection,” said Singleton. “We just hope that when you get a city with more resources, wealth, and privilege, that these people will feel enough empathy and compassion to use their resources to help those who are less fortunate. You want people to pull one another up, to be connected, to help one another.”

“It’s very much a play about what we take for granted,” said Casas. “So many people talk about the arts as an escape from their real life, but then what do you do in real life? Are you actually engaging? I want people to come away from the play knowing the crisis in Flint isn’t over, and I want people to think about what change means in their own lives—whether it’s in Flint, in the university, or in their own community.”

Flint will be premiered at the Arthur Miller Theatre from April 4-7 and 11-14, 2019 in conjunction with an art exhibition and symposium (download the flyer [PDF]). Tickets at tickets.smtd.umich.edu. Subsequent presentations will take place in Flint and potentially other Michigan locations.