Alcina

By George Frideric Handel

based on a fairy tale from Ariosto’s poem Orlando Furioso

Libretto adapted from the one written by Antonio Fanzaglia, in the opera L’isola d’Alcina by Riccardo Broschi

University Opera Theatre • University Philharmonia Orchestra

March 28-31, 2019 • Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre

A beautiful sorceress, Alcina, lures men to her enchanted island for love, only to turn them into objects or animals when she tires of them. Her current obsession is the knight Ruggiero, a young man who under her spell has forgotten about his fiancée Bradamante. Bradamante, disguised as her own brother, arrives on the island determined to rescue Ruggiero. The plot thickens when Alcina’s sister, who is betrothed to someone else, falls in love with the “brother.” The story proceeds with typical Baroque complicated twists and turns in a dramatic rendering about the differences between real love and fantasy infatuation. Moral behavior will win out before Alcina adds more trophies to her domain.

The third of Handel’s operas to be based on the epic poem Orlando furioso (with Orlando and Ariodante), Alcina debuted at the Covent Garden Theatre in London in 1735 to great acclaim. Just a few of the exquisite arias are the famous “Tornami a vagheggiar,” “Verdi prati,” and “Ah, mio cor.” The opera is considered today to be one of the greatest of the composer’s. A moving story of love’s fickleness and faithfulness, Alcina features some of Handel’s most alluring music.

Creative Team

Conductor/Music Director: Stephanie Rhodes Russell

Director/Scenic Designer: Grant Preisser

Assistant Conductor: Rotem Weinberg

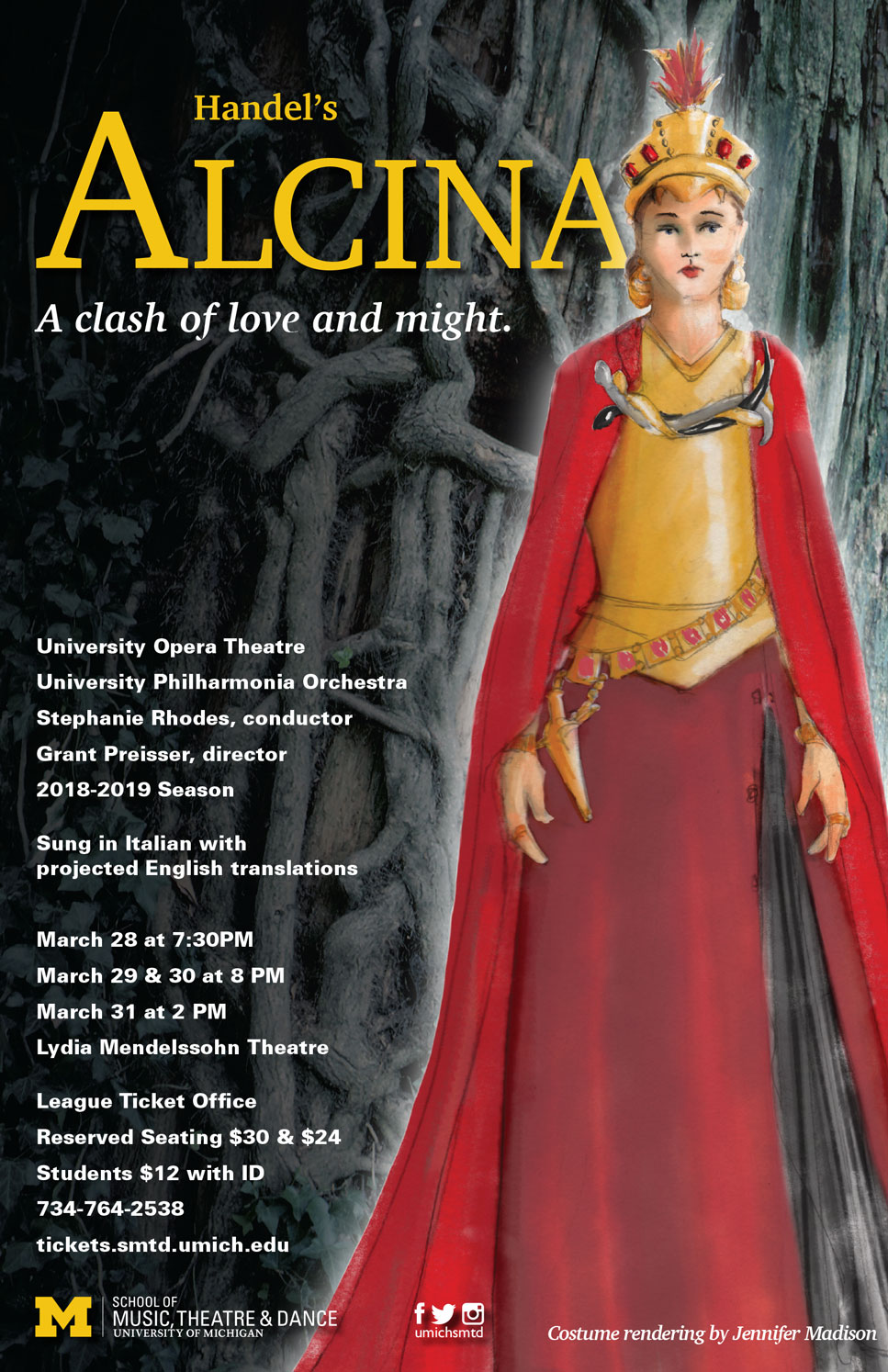

Costume Designer: Jen J. Madison

Lighting Designer: Rob Murphy

Wig and Makeup Designer: Erin Marie Schwob

Diction Coach: Timothy Cheek

Chorus Master: Adrianna Tam

Repetiteurs: Michelle Papenfuss, Bernard Tan

Fight Choreographer: Stephanie Fitt

Stage Manager: Caroline-Michele Uy

Supertitles: Grant Preisser

Cast

Thursday & Saturday/Friday & Sunday

Alcina: Kelly Ann Bixby/Rose Mannino

Ruggiero: Sedona Libero/Andrew Lipian

Morgana: Lucia Helgren/Francesca Napolitano

Oronte: Brent Doucette/Nicholas Music

Bradamante: Antona Yost/Madison Montambault

Melisso: Jacob Surzyn/Alan Williams

Oberto: Danielle Barnett/Catherine Moss

Ensemble: Sofie Aaron, Julia Bezems, Summer Brogren, Adam Chase, John Faubert, Julia Fertel, Andrew Hallam, Natalya Matskevych, Deirdre McKeever, Jack Merucci, Jack Nadler, Aldo Panado Girard, Samira Plummer-Brown, Juliet Schlefer, Daniel Simaz

Resources

On the surface, Alcina is a fantasy on a grand scale: warriors, witches, magic, enchanted beasts, and, of course, the universal struggle of good versus evil. However, it has also a much deeper exploration of love, passion, and the human condition. It pits true, chaste love against the hedonistic, selfish pursuit of pleasure.

The plot of Alcina derives from a fairytale in the epic poem Orlando Furioso by the Italian poet Ludovico Ariosto, and is one of three operas by Handel derived from this source. Orlando Furioso, or The Frenzy of Orlando, appeared in its complete form in 1532. Orlando is the Christian knight known in French (and subsequently in English) as Roland. The story takes place against the background of the war between Charlemagne’s Christian paladins and the Saracen army that has invaded Europe and is attempting to overthrow the Christian empire. One of the great works of Italian literature, the long narrative poem is about war, love, and the romantic ideal of chivalry. It mixes realism and fantasy, humor and tragedy. The stage is the entire world, with a large cast of characters featuring Christians and Saracens, soldiers and sorcerers, and fantastic creatures including a gigantic sea monster called the orc and a flying horse called the hippogriff. Many subplots are interwoven in its complicated episodic structure, but one of the most important is the love between the warriors Bradamante and Ruggiero, and their war against the Infidels, in this version represented by Alcina herself.

Handel and his London librettist, Antonio Marchi, took their text from Riccardo Broschi’s opera L’isola d’Alcina with libretto by Antonio Fanzaglia, albeit with quite a few changes. Alcina was composed for Handel’s first season at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in London. It premiered in 1735, and like the composer’s other works in the opera seria genre, Alcina fell into obscurity after a production in 1738. It was not performed again until a production in Leipzig in 1928. Modern interest came about when Joan Sutherland sang the title role at Venice’s La Fenice and at Dallas Opera in 1960. It has since been revived by many regional opera companies as more of Handel’s operas are getting produced and explored on the contemporary stage. This may seem surprising given the antiquated form and archaic plots. However, Handel creates compelling characters with a depth of feeling and fleshed out psychology not found in later operas that are more about situational dynamics. The relationships, feelings, and trials of these characters are as contemporary now as they were universal in the eighteenth century.

This production aims to honor the Baroque tradition of the piece, while also filtering it through a contemporary youthful exploration of this treatise on love in all of its forms. In the Baroque theatre, the garden is representative of erotic love. Heroes leave their civilized world and lose their way in the dangerous groves of earthly delight, Alcina’s enchanted island. There they are challenged to discover their true selves, triumph over their weaknesses, and return renewed to the real world. However, in Alcina, Handel’s music provides a counterpoint to the moralizing nature of the poetry. Handel acknowledges that the erotic garden is an essential part of the human experience. Human nature’s craving to prolong sensory pleasure is aptly symbolized by Alcina’s never-ending procession of transformed men held captive in a kind of dream by the promise of endless ecstasy. As one listens to the glorious music of Alcina, one can easily understand that desire for ecstasy. Any return to reality from the rich satisfaction of Handel’s music leads to an immediate sense of loss, but also to the exquisite memory of indescribable pleasure. It is this poignancy that best represents Alcina, a wicked character who can’t help but break the heart of anyone who will listen.

Act I

Bradamante, disguised as her brother Ricciardo, and Melisso, her former tutor and confidante, are shipwrecked along the shore of the witch Alcina’s island. With the help of a magic ring they intend to break the spell which binds Ruggiero, Bradamante’s betrothed, to Alcina, and to release her other captives, who have been variously transformed. Bradamante and Melisso are greeted by Alcina’s sister, Morgana, and they pretend to have lost their way. Morgana immediately falls in love at first sight with “Ricciardo” (Bradamante), although she is betrothed to Oronte, the commander of Alcina’s forces.

Morgana leads them to Alcina, who greets the strangers by inviting them to stay on her island. She leaves Ruggerio with them to tour the island. They are stopped by a boy, Oberto, who asks Melisso and Bradamante to help him to find his father, Astolfo. It is clear to them that Astolfo must have been changed into a wild beast, like so many others. Melisso and Bradamante, finding themselves alone with Ruggiero, try to confront him, but Ruggiero treats them with contempt. He longs only for Alcina’s return, and leaves them.

Oronte comes upon Bradamante and Melisso, having already discovered Morgana’s passion for “Ricciardo.” Incensed he challenges them. Morgana intercedes, spurning Oronte, and defending “Ricciardo.” Later, Oronte meets Ruggiero still looking for Alcina. He sews the seeds of jealousy, telling Ruggiero of Alcina’s treatment of her past lovers. When Ruggiero refuses to believe in her infidelity, Oronte instead lies to him that Alcina now loves “Ricciardo” instead of him. Mad with jealousy, Ruggiero confronts Alcina with this supposed love. Hurt, she strongly denies it and reaffirms her love for Ruggiero, in front of Bradamante. Seeing this Bradamante cannot resist revealing her identity to Ruggiero, though Melisso quickly denies it. Ruggiero chooses to believe Melisso, and assumes “Ricciardo” is trying to conceal “his” love for Alcina.

Morgana rushes in with the news that Alcina intends to prove her love to Ruggiero by turning “Ricciardo” into a wild beast. Morgana urges “him” to escape, but “Ricciardo” (Bradamante) tells her to go back to Alcina to say that “he” cannot love her, as “he” loves another. Morgana assumes “he” is referring to her, and Bradamante allows the deception. Morgana rejoices in “Ricciardo’s” love.

Ruggiero wanders the island lamenting Alcina’s absence, but he is confronted by Melisso, now disguised as his old tutor, Atlante. He reminds Ruggiero of his duty, and when Melisso puts the magic ring on his finger, the island is revealed as it really is, empty of all grandeur and beauty. Ruggiero immediately longs to see Bradamante and repair the damage caused by Alcina. Melisso tells him of the plans for escape. Ruggiero is to put on his armor, and pretending to long to hunt in the forest, make his escape with Melisso and Bradamante. Although he is now free of the enchantment, he doesn’t know what to believe. When he next sees Bradamante he cannot be sure that Alcina has not disguised herself as Bradamante to keep him in her power. Bradamante is in despair, and Ruggiero, left alone, fears for the consequences if, after all, he has again failed Bradamante. In a rage, Alcina is alone in her throne room preparing to cast the spell which will turn Bradamante into a wild beast. Morgana interrupts her, and she is followed by Ruggiero, who, without revealing that he no longer loves Alcina convinces her not to enact this spell to convince him of her love. He then persuades her, against her will, to let him go hunting. Oberto reappears, still lamenting his father’s disappearance. Alcina is amused, and offers him hope of reunion. Oronte brings news of the intentions of Ruggiero, Melisso and Bradamante to flee. Alcina laments her fate.

Act II

Oronte taunts Morgana with “Ricciardo’s” defection, but she refuses to believe him. Bradamante interrupts them with Oberto, who continues to search for his father. Ruggiero arrives and reunites with Bradamante. Morgana sees them in love and is outraged. She can’t believe “Ricciardo” is Bradamante and that Alcina has been betrayed by Ruggiero. Alcina attempts to summon her spirits to prevent Ruggiero leaving her, but instead she finds they don’t answer her command.

Morgana tries to regain the affections of Oronte, but as he swore to do earlier, he rebuffs her. Ruggiero and Alcina unexpectedly meet, and she demands to know why he is leaving her. When he tells her that he must return to his duty and his betrothed, she dismisses him and swears vengeance. Melisso, Bradamante, and Ruggiero prepare to rout Alcina’s forces, and Bradamante swears to leave the island only when all Alcina’s victims are released.

Alcina has cloistered herself in her palace, where Oronte informs her that her forces have indeed been defeated by the intruders. She longs for oblivion, but Oberto has snuck into her throne room to remind her of her promise to reunite him with his father. She maliciously brings a lion to Oberto, and orders him to kill it. He knows it must be his father and, refusing, threatens her instead. They are interrupted by Ruggiero and Bradamante who have come to destroy Alcina’s power. In an attempt to prevent them, Alcina forswears any evil intentions, claiming only desire for their happiness. She has lost all hope of being trusted, and Ruggiero shatters her enchanted cauldron. Alcina and Morgana are consumed by their broken magic, and the end of Alcina’s power causes her palace to be ruined and the island and those on it to transform back to their natural state.

-Grant Preisser

The University of Michigan is located on the territory of the Anishinaabe people. In 1817, the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Bodewadami Nations made the largest single land transfer to the University of Michigan, ceded in the Treaty of Fort Meigs, so that their children could be educated. We acknowledge the history of native displacement that allowed the University of Michigan to be founded. Today we reaffirm contemporary and ancestral Anishinaabek ties to the land and their profound contributions to this institution.