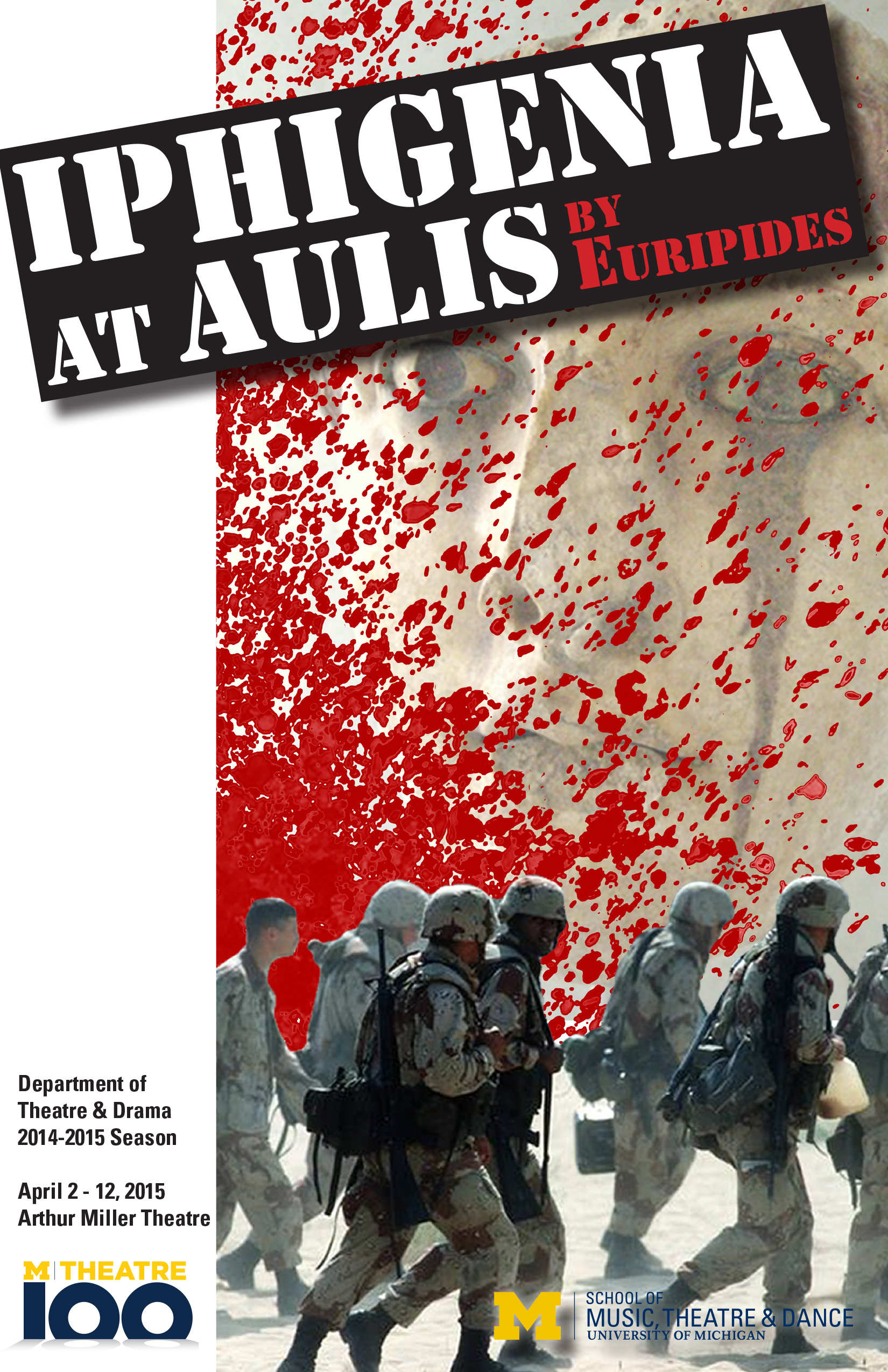

Iphigenia at Aulis

by Euripides, translated by Don Taylor

Department of Theatre & Drama

April 2-12, 2015 • Arthur Miller Theatre

The Story: Prepared to exact revenge on Troy for the abduction of Helen, the Greek army is stuck at the port of Aulis, stymied by unfavorable winds. As his men grow restless, their commander Agamemnon grows desperate to retain his command. Persuaded by his priests that the only way to set sail is through familial sacrifice, Agamemnon sends for his wife Clytemnestra and daughter Iphigenia under the pretext of a royal wedding to the hero Achilles. When the truth reveals itself, the two women and Achilles plead for young Iphigenia’s life against the swell of a growing mob.

Background: Euripides (480 BC – 406 BC) is the author of over 100 plays, 19 of which survive. Iphigenia at Aulis is the last extant work by the Greek playwright. One of the great anti-war plays, Iphigenia exemplifies how the momentum of war can propel individuals and a nation toward the unspeakable. In 1989, the late English playwright Don Taylor, a key figure in the golden age of television drama, translated, directed, and produced Iphigenia for the BBC, starring Fiona Shaw. Staying true to the original, Taylor’s translation resonates with parallels to the horrors of war that Euripides decried over two thousand years ago.

Artistic Staff

Director: Malcolm Tulip

Scenic Designer: Angela Alvarez

Costume Designer: Kayleigh Laymon

Lighting Designer: Rob Murphy

Sound Designers: Evan Klee-Peregon

Diction Coach: Henry Reynolds

Assistant Director: Annette Masson

Dramaturgs: Clarisza Runtung, Christian Axelgard, Megan Wilson

Stage Manager: Sherry Green

Cast

Agamemnon, Commander in Chief of the Greek Army: Ian Johnston

“Old” Man, servant of Agamemnon: Keem Avraham

Menelaus, brother of Agamemnon and husband of Helen: Jordan Rich

Achilles: Peter Donahue

Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon: Blair Prince

Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon: Anastasia Zavitsanos

Messenger/Soldier: Samuel Kassover

Soldiers: Kevin Corbett, Jeffrey Fox, David Newman

Chorus: Zoey Bond, Michaela Burton, Lila Hood, Sara Frost, Jackie Murray, Liz Raynes, Madeline Rouverol, Emily Shimskey, Molly Wear

Resources

About the Play

Euripides was known for bending convention and testing the limits of the tragic genre. He embraced musical innovations scorned by more traditional thinkers. His plays are not always straightforwardly tragic, a few even have happy endings, although it is worth noting that ancient definitions of tragedy differ from the modern sense of the word. In antiquity, a drama with a happy ending could still be a tragedy. Some of his linguistic patterns show influence from comedy, and his plays show interest in alternate re-tellings of myth, philosophical and scientific thinking, marginalized voices, and the physicality of architecture and craftsmanship. Euripides has remained the most popular Ancient Greek playwright for centuries.

Iphigenia at Aulis was first performed in 405 B.C.E., the year after Euripides’ death. The play was produced in a trilogy that also included The Bacchae and was presented by Euripides’ son or nephew. The trilogy won first prize at the City Dionysia at Athens.

Prominent in Iphigenia are the intertwined themes of marriage, death, and fate: by allowing herself to be sacrificed, Iphigenia undergoes a pseudo-marriage ritual that turns out to be her funeral. The exchange of the maiden Iphigenia’s life for the adulteress Helen is a point of contention, especially for Clytemnestra, Iphigenia’s mother. Several characters justify their actions as ordained by the gods; the potency of fate is viewed differently by various characters. Even Iphigenia herself in this version of the story wrestles with the acceptance, or not, of her fate.

The famous wedding of Peleus and Thetis, the Judgment of Paris, and the rape of Helen have taken place prior to the action in Iphigenia at Aulis, and are alluded to in the play. After Helen is taken to Troy, her husband Menelaus calls upon his allies, especially his brother Agamemnon, to wage war and win her back. Menelaus has come from Sparta and Agamemnon from Argos to the port of Aulis where the Greek soldiers have gathered to head to Troy. Included in their number are many famous heroes and former suitors of Helen who swore oaths to protect Menelaus.

At the end of Iphigenia at Aulis, the Old Man re-enters to tell Clytemnestra that her child was saved by the goddess Artemis at the last moment. He states that her body was replaced by a deer on the altar while the real Iphigenia was taken to become a priestess of Artemis. This version of Iphigenia’s story is also referenced in an early Greek epic poem called the Cypria. The poem may have inspired Iphigenia among the Taurians, another play by Euripides whose narrative begins with the adult Orestes searching for his long-lost sister at the desolate sanctuary of Artemis at Tauris (modern Crimea). In Iphigenia at Aulis, however, the salvation of Iphigenia was probably not part of the original performance. Rather, most scholars believe that the “messenger ending” is an interpolation by a later editor written in order to make the two Iphigenia plays more consistent. The original ending of the play is lost and exactly what it contained is unknown.

— Christian Axelgard & Megan Wilson, dramaturgs

The Mythological Characters

Clytemnestra, the daughter of Tyndareus and Leda, is the half-sister of Helen. She is married to Agamemnon with whom she bears Iphigenia and Orestes. After the events of Iphigenia at Aulis, she returns to Argos while Agamemnon continues on to Troy to continue the campaign. Upon Agamemnon’s return home, Clytemnestra kills him in revenge for his sacrifice of Iphigenia. Years later, their son Orestes will avenge his father, killing Clytemnestra and Aegisthus at the behest of Apollo. As she dies, Clytemnestra invokes the Furies to plague Orestes until he can finally resolve the cycle of bloodshed.

Agamemnon will survive as the commander of the victorious, ten-year Greek campaign against Troy, albeit with the blood of countless Greeks and Trojans on his hands. He returns home with a Trojan princess, Cassandra, as his prize. Both are slain at the hands of Clytemnestra and her new lover, Agamemnon’s cousin Aegisthus.

Menelaus is the brother of Agamemnon and the husband of Helen. After the Trojan War, Menelaus and his fleet are made to wander around, including into Egypt, for having forgotten to sacrifice to the gods before his departure from Troy. He eventually returns home wealthy from possessions gathered on the way.

Iphigenia is the eldest child of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. At the time of the play’s events, she has just reached marriageable age, probably around 14 years old for an upper-class, ancient Greek young woman. Because upper-class marriages were usually arranged by parents for strategic purposes, it is plausible that Iphigenia’s father could have betrothed her to the warrior Achilles. It is less plausible, even in antiquity, that a father would ever be willing to sacrifice his child. However, Agamemnon is depicted in Iphigenia at Aulis as acting under compulsion: between the forceful will of the army and that of the gods, he believes he has no choice.

Achilles, who was not a suitor of Helen, is a ferocious and much feared warrior at Troy. He will die before Troy falls and is buried with great honors.

Orestes is the youngest child of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. He avenges Agamemnon by murdering his mother and Aegisthus. Hounded afterwards by the Furies, he seeks help from Apollo at Delphi and Athena at Athens to assuage his guilt. In some myths he must also go to his uncle Menelaus at Sparta or to Tauris on the Black Sea in order to rescue his sister Iphigenia, a priestess of Artemis.