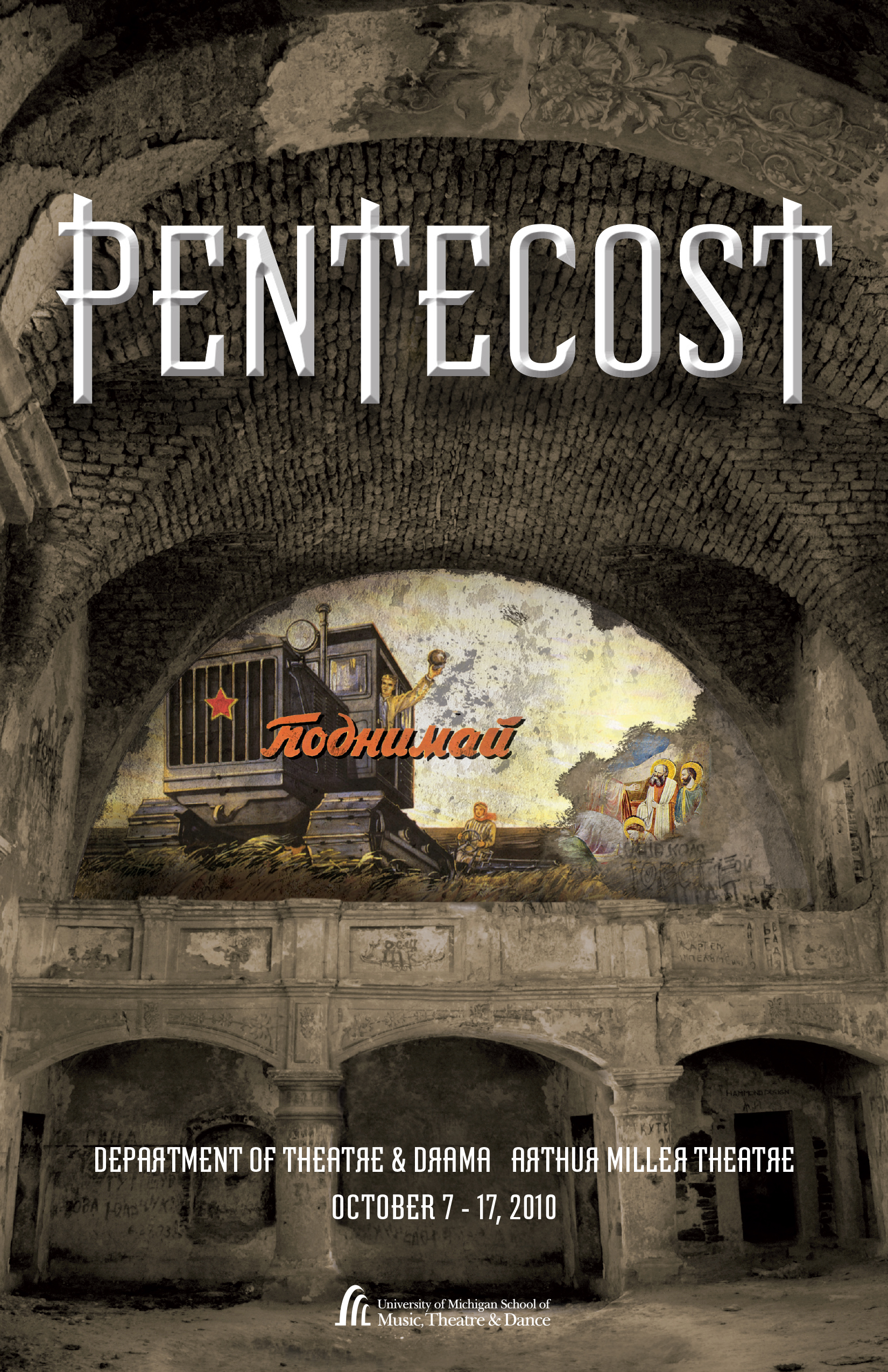

Pentecost

a drama by David Edgar

Department of Theatre & Drama

October 7-17, 2010 • Arthur Miller Theatre

The Story: In an abandoned church in a post-Soviet-era Eastern European country, a museum curator has discovered a fresco that could radically change the history of western art and re-establish her country’s national identity. As she struggles through language barriers to authenticate the find, competing interest groups – from art historians, to religious groups, to the state itself – vie to claim ownership of the work. Suddenly, an unexpected situation changes the power structure, leading to surprising and shocking conclusions for both the artistic mystery and political intrigue.

Background: Best known for his Tony Award-winning adaptation of The Adventures of Nicolas Nickleby, David Edgar is one of England’s premier contemporary political playwrights. Commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company, Pentecost is the second in a trilogy of political plays dealing with the transition of Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The work won the esteemed Play of the Year Award from the London Evening Standard in 1995. Wonderfully thought-provoking, Edgar’s drama presents a dazzling array of ideas about how we define nationalism, conflicting attitudes toward art, and the need for a global community. The New York Times declared “In a modern play that risks dealing with bravery, passion and sacrifice, prejudice and pride — the inevitability of war and the improbability of peace — Mr. Edgar imagines the unimaginable. With bitterness. And with hope.”

Artistic Staff

Director: Malcolm Tulip

Scenic Designer: Marguerite Woodward

Costume Designer: Corey Lubowich

Lighting Designer: Adam McCarthy

Sound Designer: Colin Fulton

Creative Acoustics Consultant: Jonah Thompson

Dialect Coach: Annette Masson

Assistant Director: Roman Micevic

Assistant Dialect Coach: Bonnie Gruesen

Dramaturg: Matthew Bouse

Stage Manager: Rachael D. Albert

Cast

Gabriella Pecs, an art curator: Emily Berman

Oliver Davenport, an English art historian: Joey Richter

Father Sergei Bojovic, Orthodox: Yuriy Sardarov

Father Petr Karolyi, Catholic: Matthew Socha

Mikhail Czaba, a minister: Myles Mershman

Pusbas, the leader of Heritage: Josh Berkowitz

Leo Katz, an American art historian: Reed Campbell

Anna Jedlikova, a former dissident: Keleki Gottschalk

Toni Newsome, an English TV hostess: Emma Donson

Girl/Restorer: Brittany Uomoleale

Swedish Man/Restorer/Commando: Gordon Granger

Soldier/Commando: Devin Rossinsky

Czaba’s Secretary/Policewoman: Quinn Scillian

Yasmin, Palestinian Kuwaiti: Alli Brown

Raif, Azeri: Dan Rubens

Antonio, Mozambican: Jeffery Owen Freelon, Jr.

Amira, Bosnian: Elly Jarvis

Marina, Russian: Alexandra Eden

Grigori, Ukrainian: Jesse Peri

Abdul, Afghan: Derek Joseph Tran

Tunu, Sri Lankan: Sango Tajima

Nico, “Bosnian” Roma: Paul Koch

Cleopatra, “Bosnian” Roma: Aimée Garcia

Fatima, Kurd: Madeline Sharton

Sponsors

The School of Music, Theatre & Dance acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Resources

From the Dramaturg

“Restoration”, “Conservation”, and the Debate over Presenting Art

“Art restoration” and “art conservation” may appear to be nearly identical. This may seem like a trivial linguistic choice. In fact, they represent opposing viewpoints on the role modern institutions should play in the upkeep of classical art. However as David Edgar’s characters demonstrate, there is a hotly contested debate over “restoration” and “conservation.” “Restoration” projects return works to their original conditions. Restorers, skilled artists hired by the museum or gallery, often repair damaged works. Fading sections are touched up; punctures and cracks are filled. The goal here is brighter colors, sharper detail, and a “like new” appearance. Restoration had been popular and common; however, there has been a backlash against this work. Scholars argue that art should not be “restored” to a past appearance, but “conserved” for future generations. Conservation is focused on establishing the causes of deterioration, and preventing further aging. The conservationist, often from a scientific background, performs a number of tests on the painting to understand its composition to determine the best methods of preservation, and, any treatment applied to the painting is entirely reversible. Overzealous restorations are a major source of controversy within the art world. Botched restorations, where unwise chemical treatments or incorrect pigments have resulted in discoloration and damage, require additional work from cautious, preventative, conservationists. The existence of advocacy groups such as Artwatch International Inc, which monitors restoration projects and blocks those it deems harmful, illustrates that the ideological disputes seen in Pentecost are as fiercely argued in real life as in Edgar’s play.

— Matthew Bouse

Hope Persists in a Fractured World

In Pentecost, a pair of art historians discovers a “missing link” between the Renaissance and Medieval art worlds inside an Eastern European church. While debating plans to restore the painting and relocate it to their national art museum, the church is overrun by a band of refugees searching for sanctuary. The historians are taken hostage as bartering chips for the refugees’ safe passage into the Western world. The play examines the social and political climate in Eastern Europe at the end of the Twentieth Century and the position of displaced persons in the world.

Last winter, David Edgar, author of this season’s Pentecost, visited campus with the Royal Shakespeare Company. While in Ann Arbor, he sat down with the Pentecost company to speak about, among other things, the genesis of his play. Edgar wrote the play after the fall of the Berlin Wall in response to changing attitudes towards Eastern Europe. In 1989, immediately following the fall, Europe was in a state of celebration. Decades of division between East and West were crumbling, and the continent was washed with a unifying sense of community. Within a few years, however, attitudes had changed. The transition from socialist states to independent republics was neither smooth nor bloodless. As war broke out in the East, refugees looking to the West found closing doors. The sense of inclusion and of a European community that had triumphed only years earlier were now replaced with feelings of alarm and exclusion. As the East struggled to find its way, Western Europe became concerned with possible mass immigrations, unsure of the effect that waves of fleeing immigrants might have on their stable cultures. This is the war torn, divided Europe against which Pentecost is set.

The refugees in Pentecost come from disparate, diverse backgrounds, each with its own colorful, rich history. The characters are drawn from across the globe with origins in Africa, Central Asia, The Middle East, Eastern Europe, and South East Asia. What they have in common is the strife and struggle in their lives, and the human horror witnessed in their homes. The Twentieth Century has been called the “Century of Genocide” — as Western colonial rule gave way to fragile democracies in Africa, Asia, and elsewhere, vicious despots fought their way to power. In Eastern Europe, former Soviet and Yugoslav republics fell into brutal civil wars as political factions used military might to secure governmental control. Ethnic cleansing, the tactical elimination of opposing ethnic groups in order to secure territory for one’s own, were characteristic of these conflicts. In places like Bosnia and Herzegovina, populations of Croats, Serbs, and Bosniaks were purged as these ethnic peoples scrambled to divide the former Yugoslavia. In Mozambique, civilians caught in civil war were terrorized, maimed, and murdered without ever really knowing which political party was persecuting them and which was rescuing. For many of the refugees, decades of civil war would mean never knowing a world without violence and fear.

As dire as the situation sounds, the play is not without hope. The title, Pentecost, comes from a biblical story out of the book Acts. In the story, the Holy Spirit rushes over the Apostles and brings them a multitude of tongues to speak in. The Apostles are amazed to find that they can understand each other in these new languages; the barriers of language have been blown away. In Pentecost, the characters begin to understand and relate to each other, circumventing the divisions of language, as well. It is the characters’ humanity that brings them together — on stage, the refugees and their hostages form a community. They exchange jokes and share the folk stories of their homelands. Edgar uses these scenes to underscore the universalities of these people. The stories are all variations on the same plot with only a little local coloring. When addressing the company, Edgar was careful to draw our attention to the hopefulness buried beneath the play’s conflict. He reminded us that the title’s spirit, the celebratory feast Pentecost, is as important as its meaning.

This underlying hopefulness is not unwarranted. By the end of the 1990’s, many of these displacing wars came to an end. Many of the refugees’ homelands are now entering their second decade of free elections. There are still, of course, numerous conflicts that persist today, and, many people are still unable to return to their homes. In Azerbaijan, peace treaties have not been reached with Armenia, and a shaky cease fire keeps thousands displaced. And in Afghanistan, American and NATO troops continue to combat the Taliban and their allies. However, in many parts of the world, the scars of the Twentieth century are healing, and the post-Socialist and post-Colonial worlds are convalescing into stable democracies. As the characters discover, the lexicon of the Modern age includes combative words such as shrapnel, ambush, and flight; discriminating words such as roadblock, buffer, and quota; but also, words such as huddled, yearning, and free.

Matthew Bouse, Dramaturg

Bachelor of Theater Arts, Class of 2011

From the Director

In 1998, I was in Ames, Iowa, by the banks of the Skunk River, to meet with designers at Iowa State University’s Theatre Department in preparation for a production to be developed during an upcoming residency I was to embark upon that fall. Arriving from the airport to the theatre, I was greeted by the sight of young actors strolling on grass verges, sitting on steps and railings, standing nose-to-the-wall chirruping in languages from across Europe and Africa as well as the Middle and Far East. Gregg Henry, then Chair of the Department and now Artistic Director of the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival, told me that they were preparing for their roles in a play called Pentecost by David Edgar. The focus, commitment and concentration of the young actors were immediately apparent and impressive.

Eleven years later not far from the banks of the Huron River in Ann Arbor, this image came back to me while trying to choose a play for the 2010-11 season. Given the challenges of the piece – the number of the characters to be costumed, the set that would be need to be built and painted to match the text, the demands upon the actors; learning art history, Sinhalese, Bulgarian, Arabic, Turkish and others, understanding the Balkan conflict of the 1990’s, and much more – I am grateful on behalf of the students to the Department and to University Productions and to the donors for their support for a project which has been so rewarding for all involved.

— Malcolm Tulip