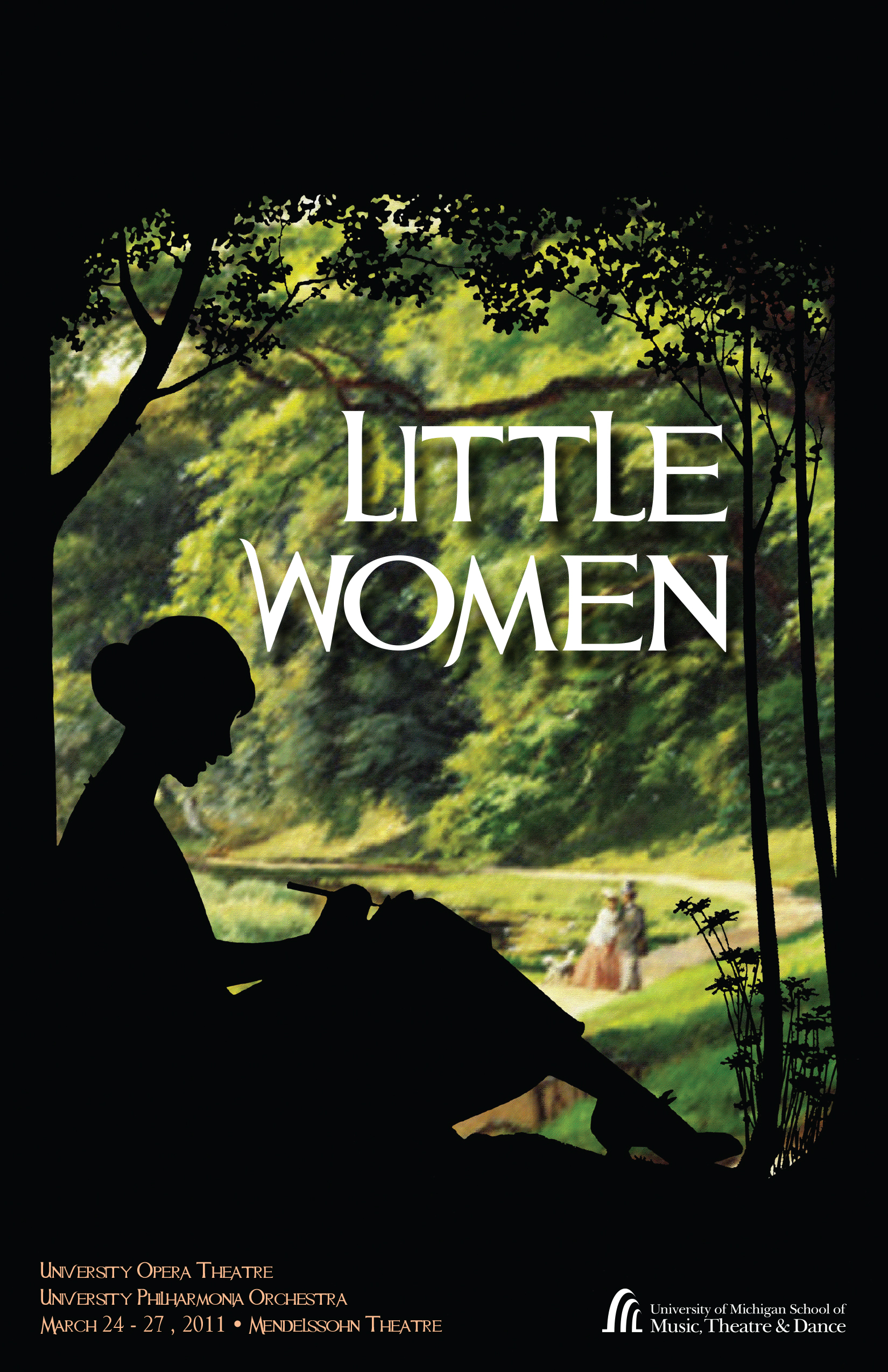

Little Women

an opera by Mark Adamo

University Opera Theatre • University Philharmonia Orchestra

March 24-27, 2011 • Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre

The Story: Adapted from the beloved novel by Louisa May Alcott, Little Women is more than a poignant coming-of-age tale that has beguiled audiences for over a century. The four inseparable March sisters – Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy – are devoted to each other and the warm cozy home they share with their parents. Unfortunately, childhood doesn’t last forever and growing up ultimately means growing apart. Unwilling to accept the change, Jo does everything she can to stem the passage of time – even leaving home. But when Beth’s illness brings her racing home to transformation beyond recall, Jo must reconcile her childish wishes with the mature twists in her own life.

Background: Acclaimed by The New Yorker critic Alex Ross as “one of the best opera composers of the moment,” composer-librettist Mark Adamo achieved unprecedented success with his first opera Little Women. Premiered by the Houston Grand Opera in 1998, Little Women has become one of the top ten performed operas nationally and internationally with fifty-five different productions. His latest commission is for the San Francisco Opera, The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, set to premiere in June 2013. The Los Angeles Times declared Little Women “A strong poetic text married to music of charm and tunefulness…a joy in every way.” Filled with vivacious music, wit, and charm, Little Women is an engaging opera that evokes our own wishes to freeze moments in time.

Artistic Staff

Director: Robert Swedberg

Conductor: Christopher James Lees

Assistant Conductor: Warren Puffer Jones

Scenic Designer: Corey Lubowich

Costume Designer: Corey Davis

Lighting Designer: Sarah Petty

Wig, Hair & Makeup Designer: Erin Kennedy Lunsford

Diction Coach: Timothy Cheek

Répétiteurs: Matthew Brower, Justin Snyder

Stage Manager: Jordan Braun

Cast (Thursday-Saturday/Friday-Sunday)

Jo: Kristin Eder/Elizabeth Lenz

Laurie: Kevin Newell/Kyle Stegall

Meg: Christine Reinard/Emily Goodwin

Beth: Elise Turner/Kelly Hedgspeth

Amy: Mary Martin/Amy Petrongelli

John Brooke: Carl Frank/Steven Eddy

Cecilia March: Amanda Cantu/Sarah Davis

Alma March: Sarah Nicole Batts/Maureen Ferguson

Friedrich Bhaer: Nicholas Ward/Brandon Grimes

Gideon March: Brian Rosenblum/Benjamin Sieverding

Mr. Dashwood: Glenn Ellington

Spirits: Sarah Voice, Stephanie Hradsky, Nadya Hill, Jayme Kelmigian

Sponsors

The School of Music, Theatre & Dance acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Media Sponsorship by WRCJ.

Resources

Synopsis

Prologue

Concord, Massachusetts – 1870

The dark attic of the March house – Jo, distraught, greets her friend Laurie. He’s just married Jo’s younger sister Amy; but has he only married Amy to stay near Jo? Worse: Laurie adores Amy – nothing is as it was – and the opera spirals back in time to show why Jo tried to keep it so.

Act I

Scene 1: The attic, three years before

Jo and her sisters Meg, Beth, and Amy make games of their chores. Laurie tauntingly tells Jo that his tutor, John Brooke, keeps Meg’s glove because he loves her. Jo, alone, sketching a story, fearfully denies that Meg might love him too.

Scene 2: In front of the March house, weeks later

Brooke courts Meg. Jo urges the family to reject him. Cecilia, the girls’ aunt also scorns Brooke: but Meg, resolved, accepts him. Her family celebrates; but Jo accuses Meg of abandoning her.

Scene 3: The March garden, the following summer

Meg and Brooke adapt their parents wedding vows. A feverish Laurie pleads for Jo’s love. She spurns him; stung, he flees. Beth, secretly ill, collapses as Meg cries for help.

Act II

Scene 1: The offices of the Weekly Volcano, a New York City fiction tabloid, one year later

A triumphant Jo sells a story; back at her boarding house, she writes her increasingly atomized family. A new acquaintance, Friedrich Bhaer, invites her to the opera.

Scene 2: Simultaneously, Jo’s boarding house; the March parlour; sunny Oxford lawn

Jo and Bhaer engage in flirtatious debate while, in Oxford, Amy tests Laurie’s feelings for Jo. Beth rages at the piano. Bhaer ardently recites Goethe to Jo: then Alma’s desperate telegram interrupts them. Jo flees to Concord.

Scene 3: Beth’s bedroom, three sleepless nights later

Beth dozes as her family keeps vigil. Jo bursts in; Beth bids her family leave. Beth urges Jo

to accept her impending death.

Scene 4: The March house, the following spring

Cecilia baits Jo with Amy’s letter about loving Laurie. Jo wearily admits Bhaer may have abandoned her. Cecilia urges Jo to choose solitude; refusing, Jo retreats to the attic.

Scene 5: The attic

As in the beginning, Jo, distraught. Laurie, appearing, again reminisces; but now Jo rejects the past. Her sisters materialize as memories: Jo, in emotional exorcism, celebrates and releases them. Bhaer – her future – appears: Jo extends her hand to him.

— Synopsis courtesy of G. Schirmer

From the Composer

Little Women, that indispensable chronicle of growing up female in post-Civil War New England, has most often materialized on screen and stage as the romance of a free-spirited young writer torn between the boy next door and a man of the world. Closer reading of Louisa May Alcott’s novel revealed to me a deeper theme: that even those we love will, in all innocence, wound and abandon us until we accept that their destinies are not ours to control. So I shaped a libretto in which Jo’s love for her sisters regained the power it wielded in the original novel; and imagined a finale in which Jo at last accepts that even sincerest love and strongest will cannot stave off change and loss.

Jo’s journey called to mind the Buddhist suggestion that a lesson unlearned will present itself over and over again until at last the pilgrim makes progress and grasps the point. It suggested to me a score in which one could clearly hear Jo’s music of resistance tangling with and finally yielding to an unstoppable music of change. In fact, I wanted two scores: a character music sounding these protagonists’ emotional journeys, and a narrative music as distinct as I could make it from the thematic foreground.

So, Jo’s resistance theme and Meg’s and Laurie’s change theme, among others, are written in a free lyric language of triad and key. But those moments driven by language and story, rather than music and psychology, take a kind of dodecaphonic recitativo secco, designed to distinguish the flavor of the non-thematic dialogue. It’s Jo’s Act One scena, “Perfect As We Are,” which portrays her divided feelings by disrupting her long-lined F-major cantilena with careening dodecaphonic comedy, which best exemplifies what I dreamed for this opera: a music in which even the most unlike materials could fuse into a single music if the ear is sensitive and the design is sound.

I am surprised, and humbled, by the critical and popular embrace Little Women has enjoyed in the thirteen years of its life. (University of Michigan’s performances mark the 72nd of 75 past or planned engagements since the opera’s Houston Grand Opera premiere in 1998.) The list of those who have been generous to this work is endless; but I would like, above all, to thank my parents, Julie and the late Romeo Adamo, to whom Little Women is lovingly dedicated.

— Mark Adamo

Little Women on Mark Adamo’s Website

Director’s Note

The Louisa May Alcott novel Little Women was not one of my favorites. It was required reading for me in middle, or high school, and as a young, male, Californian, I remember having difficulty relating to the lives of these four 19th century sisters living in Concord, Massachusetts. I’m sure I just wasn’t reading it the right way then, and perhaps I have become more sensitive over time, but it was a wonderful surprise to discover Mark Adamo’s operatic setting, which treats the relationships of the sisters lovingly, but also draws more focus to other parts of the novel that have great appeal to a broader audience. (I’ve been joking with our marketing staff that we could help promote the opera by using the tag line: “…and guys like it too.” ) But that is not really necessary, as buzz about this opera has gotten around since its premiere, and as of last year, it was the second most-produced opera in the U.S. (after Amahl and the Night Visitors).

It is easy to see the appeal. The opera Little Women is about relationships – and how they inevitably change. That the young March sisters had vibrant bonds of sisterhood is important background, but change is the theme here. Adamo has put the eight scenes in the opera together going back in time after the prologue, first cleverly re-winding time by two years, and then working forward to the same point, but with the inevitability of change (and knowledge of what had happened) guiding the action. This dramatic structure, and the device in several scenes, of having many things happening simultaneously, makes Little Women quite different from other operas. Musically too, the piece is unique; extremely difficult to learn, but ultimately very accessible.

There are also a number of flourishes in the libretto of Little Women that I find very interesting. Some text is inspired by Bronson Alcott (Louisa’s father), or Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman, adding interesting touches of Transcendental perspective not found in the novel.

Finally, with the many roles (mostly double cast) and opportunities for our orchestra, musical staff, three student designers, stage managers, and crew, Little Women becomes an ideal vehicle for the considerable talents of our students at U-M. My wonderful new colleague – Maestro Christopher Lees – joins me in sharing with you that we all have grown in working on this piece, and I am sure you will enjoy the fruits of our efforts.

— Cordially, Robert Swedberg