Two productions in repertory, presented as part of the theme semester Opera in the Americas – American Opera with support from the Institute for the Humanities.

University Opera Theatre

March 22-26, 2006 • Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre

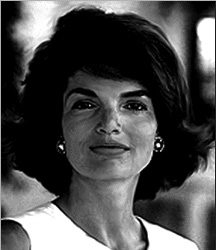

Jackie O

Music by Michael Daugherty

Libretto by Wayne Koestenbaum

Society’s fascination with celebrity and pop culture is the theme of Jackie O, a playful pop opera of facts and fancies about one of America’s most enduring icons, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Jackie attends a 1968 avant-garde New York “happening” with Andy Warhol, meets the seductive Aristotle Onassis for the first time, has a dream duet with Maria Callas, and embraces her fate as a symbol of JFK’s idealism. Jackie O captures the mystery, the tragedy, and the glamour that epitomized this pop icon.

Premiered by the Houston Grand Opera in 1997, Jackie O was composed by UM professor Michael Daugherty, who is renowned for creating music inspired by American popular culture. The opera features a melodic score that draws on jazz, pop, and classical operatic idioms. Newsweek declared Jackie O “…well grounded by Koestenbaum’s poetic libretto and Michael Daugherty’s brilliantly eclectic score… simple, catchy melodies that don’t condescend and grand symphonic carnivals that aren’t pretentious.” Daugherty is one of the most performed American composers of his generation and arguably the liveliest.

Artistic Staff

Director: Nicolette Molnár

Conductor: Kenneth Kiesler

Assistant Conductor: Robert Boardman

Scenic Designer: Vincent Mountain

Costume Designer: Christianne Myers

Lighting Designer: Michael Lincoln

Video Designer: Kristin Fosdick

Choreographers: Missy Beck-Matjias, Lisa Catrett-Belrose, Evan Faas, Jarel D. Waters

Chorus Master: John Trotter

Musical Preparation: Matthew Piatt

Wig Designer: Dawn Rivard

Stage Manager: Melissa M. Spengler

Cast

Jackie O, soprano: Hannah Williams

Elizabeth Taylor, soprano: Kelly Holst

Maria Callas, mezzo-soprano: Jody Doktor

Grace Kelly, mezzo-soprano: Marlene Inman

Andy Warhol, baritone: Nathan Brian

Aristotle Onassis, bass: Seth Mease Carico

John F. Kennedy’s voice, tenor: David F. Wilson

Paparazzi: Evan Faas, Bryan Langlitz, Alex Puette

Ballerina: Joyelle Fobbs

Ensemble: Zach Barnes, Joel Bauer, Kelly Ann Bixby, Emily Bottorff, Anthony Bucci, Megan Cox, Janine DiVita, Elizabeth Klemperer, Andrew Laudel, Andrew McGuire, Jessica Rice, Austin Stewart

Understudies

Jackie O: Amanda Kingston

Elizabeth Taylor: Sheena Law

Maria Callas: Rachel Newson

Grace Kelly: Katherine Montgomery

John F. Kennedy’s voice: Nicholas Holland

Resources

Synopsis

Act I: The Happening

1968, five years after Kennedy’s assassination. A “Happening” in New York City. Café society in extremis. Elizabeth Taylor and Grace Kelly make grand entrances; they complain about the perils of fame. To the delight of guests and paparazzi, a phone call announces that Jackie Kennedy is coming out of mourning and is returning to society. Andy Warhol explains his philosophy of art to Jackie, and she in turn confesses her melancholy convictions. Opera diva Maria Callas and millionaire tycoon Aristotle Onassis arrive at the party. The two squabble. Onassis, captivated by Jackie, bids farewell to the heartbroken Callas. He pursues Jackie, offering her a new life – refuge from the unwanted attentions of paparazzi and the greedy public. Again the phone rings, this time with news of another assassination. Jackie accepts Onassis’ offer, and they leave together.

Act II: The Island

One year later, Onassis entertains a group of men on his yacht, moored at his island. Meanwhile, Jackie reads a book. She is subject to fits of remembrance, of trance: her thoughts drift back to Jack (JFK). Callas phones Onassis and agrees to meet him at the Lido, a beach resort outside of Venice. He receives another phone call, this time telling him of his son’s fatal accident. Amid the ominous sound of sirens, Jackie and Callas step onto the island and find their eternal flames. Rivals achieving reconciliation, they reflect on their parallel traumas, on the flames’ power to create and to destroy, and on the world around them. Their reverie is interrupted by a paparazzo, who invades their privacy and takes photos of them. At Jackie’s request, Callas smashes his camera: she frees Jackie from his spell, and renders him powerless. Callas leaves the island. Jackie makes a long-overdue call to JFK on the “other side” – the afterworld. He asks Jackie to forgive him for the past; she pardons him. Transfigured by her encounter with the voice of her beloved, she recognizes that it is time to go home to America, to the fragments of the New Frontier. Changed, she submits to her role as the ambiguous incarnation of JFK’s ideals.

Notes on Jackie O

Compiled by the Humanities Institute Class 511

Jackie as an Icon

Born Jacqueline Bouvier, known to millions as Jacqueline Kennedy, and later as Jackie Onassis, Jackie has maintained a place in the American public’s mind since she first entered the spotlight during her storybook wedding to Washington’s most eligible bachelor, John F. Kennedy. Jack and Jackie rose to fame as they entered the White House. For the first time in fifty years, there were babies in the White House, and a doting young mother who seemed not to care for politics. Instead, she made it her mission to bring elegance and culture into her new home. Jackie embarked on a White House redecoration project, and then invited the public to tour her home. The White House had never seen parties like the ones Jackie threw, complete with gourmet menus and A-list guests, including Nobel Laureates, film stars, and celebrities. The beautiful young woman became known for her fashion taste, and began more than one fad as photos were taken of her landmark style. Every designer in the country lobbied to have their couture worn by Jackie. Even today one can still purchase the well-recognized “Jackie O sunglasses.” The London Evening Standard wrote of her, “Jacqueline Kennedy has given the American people…one thing they have always lacked: majesty.”

Born Jacqueline Bouvier, known to millions as Jacqueline Kennedy, and later as Jackie Onassis, Jackie has maintained a place in the American public’s mind since she first entered the spotlight during her storybook wedding to Washington’s most eligible bachelor, John F. Kennedy. Jack and Jackie rose to fame as they entered the White House. For the first time in fifty years, there were babies in the White House, and a doting young mother who seemed not to care for politics. Instead, she made it her mission to bring elegance and culture into her new home. Jackie embarked on a White House redecoration project, and then invited the public to tour her home. The White House had never seen parties like the ones Jackie threw, complete with gourmet menus and A-list guests, including Nobel Laureates, film stars, and celebrities. The beautiful young woman became known for her fashion taste, and began more than one fad as photos were taken of her landmark style. Every designer in the country lobbied to have their couture worn by Jackie. Even today one can still purchase the well-recognized “Jackie O sunglasses.” The London Evening Standard wrote of her, “Jacqueline Kennedy has given the American people…one thing they have always lacked: majesty.”

Kennedy’s assassination shocked America, and catapulted Jackie to lasting fame. All eyes were on Jackie as she ushered her two small children through public mourning. Her image as a grieving widow, which epitomized the nation’s sorrow, was immortalized. The funeral she planned was watched and remembered by millions.

When she announced her marriage to shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis, the public was again shocked. Jackie saw it as her way out, protecting herself and her children from undesired press coverage and the “Kennedy Curse” that had already taken the lives of her children’s father and uncle. The American public saw it as desertion, and felt that Jackie was turning a cold shoulder. The marriage, however, did not last long, and Jackie was soon back in the States where she lived the remainder of her life in New York City, quietly working as a publisher and as an arts preservationist.

— Caitlyn Thomson

Trends in 1960’s Politics and Culture

In 1961 the Democrats gained control of the White House. John F. Kennedy, an exceptionally charismatic politician and the youngest man to be elected to office, began his presidency pushing for numerous social reforms. His “New Frontier” plan attempted to increase federal aid to education, back urban renewal, institute federal medical care, end racial discrimination, and support the U.S. in the space race. While he accomplished raising the minimum wage and the establishment of the Peace Corps, many of his other reforms were left in the lurch when he was assassinated in 1963. Although Kennedy was among the most popular presidents of the United States, he is often criticized for the initiation of the Vietnam War and the failure of the Bay of Pigs Invasion in an attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro.

His successor, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, carried on many of his unfinished projects. Although Johnson backed the civil rights movement by outlawing public segregation and supported equal employment opportunity for both African Americans and women, he is criticized for the escalation and continued involvement in the Vietnam War. By 1967 over 600,000 troops had been stationed and the end was still not in sight. The country, specifically its youth, held multiple protests opposing both the war and continuing racial discrimination.

The most prominent leader of the civil rights movement was the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who advocated a peaceful approach towards desegregation while his counterpart Malcolm X, leader of the Black Power movement, rejected integration and initiated a number of violent confrontations with the federal government. Robert Kennedy, JFK’s younger brother and the country’s Attorney General, was also actively involved in civil rights during the late sixties. Both Kennedy and King were figures of hope in this unstable period and their loss was deeply felt when they were assassinated in 1968.

The most prominent leader of the civil rights movement was the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who advocated a peaceful approach towards desegregation while his counterpart Malcolm X, leader of the Black Power movement, rejected integration and initiated a number of violent confrontations with the federal government. Robert Kennedy, JFK’s younger brother and the country’s Attorney General, was also actively involved in civil rights during the late sixties. Both Kennedy and King were figures of hope in this unstable period and their loss was deeply felt when they were assassinated in 1968.

Social unrest mirrored the political turmoil during the sixteies. The nation questioned the credibility of its leaders and this in turn led to prevalent personal instability which was reflected in the more arbitrary aspects of the culture of the decade.

The 1960’s were in part a time of freedom, innocence lost, scandal, war-time behaviors, sex, drugs, and rock and roll. There were efforts to break free of old traditions and create new ones. Music changed as rock and roll continued to develop. The Beatles overtook the popularity of Elvis Presley, and other musicians such as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez introduced social commentary in their music. Woodstock took place in 1969 making history as the first concert to combine the world’s most popular musicians in one event. Hippies and the drug culture had an uprising as the recreational use of cannabis and other drugs, especially new synthetic drugs such as LSD, gained popularity.

Television and film captivated the country with ideas of outer space, and the future: Dr. Who began in 1963, Star Trek made its debut in 1966, and 2001: A Space Odyssey hit theatres in 1968. Laugh In was the most popular television show of 1968. Its sketches ranged from absurd comedy to political satire, and it is rumored that the show’s significant pull on the public enabled Richard Nixon to win the close 1969 election as a result of his appearance on the program.

Television and film captivated the country with ideas of outer space, and the future: Dr. Who began in 1963, Star Trek made its debut in 1966, and 2001: A Space Odyssey hit theatres in 1968. Laugh In was the most popular television show of 1968. Its sketches ranged from absurd comedy to political satire, and it is rumored that the show’s significant pull on the public enabled Richard Nixon to win the close 1969 election as a result of his appearance on the program.

The visual arts moved away from more traditional forms and towards ‘Pop Art’ and ‘Conceptual Art.’ Artists such as Andy Warhol used iconic images to capture America’s popular culture. Roy Lichtenstein drew heavily from comic books and advertisements, and described himself as being as “artificial as possible.”

— Rachael Brady and Stephen Sposito

The Dreamy Kid

Music by James P. Johnson

Play by Eugene O’Neill

De Organizer

Music by James P. Johnson

Libretto by Langston Hughes

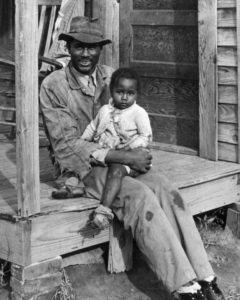

Don’t miss these two rare one-act operas composed by jazz and blues great James P. Johnson. The Dreamy Kid is an early work by Eugene O’Neill which centers around a black man on the run from the law. Torn between the need to escape and the fear of being cursed if he doesn’t visit his dying grandmother, Dreamy ultimately must chose between comforting her at the end of her life and possibly getting caught. In Langston Hughes’ De Organizer, a union organizer tries to rally sharecroppers into forming a union. Written for a union convention, the opera played once at Carnegie Hall before dropping into obscurity and was presumed lost.

African-American composer and pianist James P. Johnson, the father of stride piano, was an important transitional artist between the age of ragtime and of jazz in the early 1920s, especially for jazz piano greats Fats Waller and Jelly Roll Morton who followed him. Johnson contributed greatly to the jazz library with such songs as “Charleston,” “If I Could Be With You,” and “Carolina Shout” as well as being the favorite accompanist of Bessie Smith. Classically trained, his works were not limited to jazz, but ranged into symphonies, chamber music, and operetta — many of which have unfortunately been lost. UM Professor of Jazz James Dapogny has painstakingly reconstructed these two gems, long forgotten and neglected, of this incredible musician.

Artistic Staff

Director: Nicolette Molnár

Conductor: Kenneth Kiesler

Assistant Conductor – The Dreamy Kid: Benjamin Vickers

Assistant Conductor – De Organizer: Benjamin Rous

Scenic Designer: Vincent Mountain

Costume Designer: Christianne Myers

Lighting Designer: Andrew Fritsch

Choreographer: Natalie Malotke

Chorus Master: John Trotter

Musical Preparation: Alice Ng

Wig Designer: Dawn Rivard

Stage Manager: Melissa M. Spengler

Cast

The Dreamy Kid

Mammy, mezzo-soprano: Elizabeth Gray

Irene, soprano: Minnita Daniel-Cox

Ceely Ann, soprano: Lori Hicks

Dreamy, tenor: Lonel Woods

De Organizer

The Woman: Monique D. Holmes

A Woman: Rabihah Davis

Old Woman: Olivia Duval

Dosher: Emery Stephens

Bates, tenor: Lonel Woods

The Organizer: Darnell Ishmel

Old Man, bass: Kenneth Kellogg

The Overseer: Branden C.S. Hood

Ensemble: Mutiyat Ade-Salu, Jonathan Christopher, Rebecca Eaddy, Chris Eaglin, Kelcy Griffin, Eric Harvey, Aahlee-Charles Holloway, Monique L. Holmes, Max Kumangai-McGee, Brandon Littlejohn, Corbin Reid, Deondre Richmond, Charis Vaughn

Understudies

Irene – DK: Rebecca Eaddy

Ceely Ann – DK/A Woman – DO: Rhea Olivacce

Resources

Synopses

The Dreamy Kid

Setting: Mammy Saunder’s bedroom in a house just off Carmine Street in New York City’s West Village, 1918.

Mammy lies on her death bed awaiting a visit from her beloved grandson, Dreamy. She is being cared for by her friend and neighbor, Ceely Ann. Dreamy’s prostitute girlfriend, Irene, comes looking for him with urgent information, but is asked to leave. Dreamy arrives and confesses to Ceely Ann that he is running from the law, having killed a white man. Mammy is overjoyed at seeing her grandson and makes him promise to stay with her through her last moments on earth. Irene returns to tell Dreamy that the police know where he his. She begs Dreamy to leave with her before it is too late, but Mammy, unaware of Dreamy’s predicament, entreats him to stay. Despite Irene’s pleading, Dreamy decides to stay with his grandmother and awaits the approaching police.

De Organizer

Setting: A storage shed on a plantation in the South, late 1930s.

A group of African-American sharecroppers await the expected arrival of a union’s organizer. Before he arrives, his associate and companion, The Woman, turns up bringing union leaflets. She incites them with reasons to join the union and talks about The Organizer and their vision of a new, brighter future. The Organizer arrives and speaks about the benefits of forming a union. The meeting is interrupted by The Overseer, who tries to intimidate the sharecroppers out of joining the union, but he is overpowered and the union is established.

Notes on The Dreamy Kid

The “Negro Migration”

Since the Civil War there had been a Northward migration from the South, but by 1914 this movement included African Americans as well.

By 1915, there was a need for labor in the North as immigration to the U.S. had sharply dropped off. In 1914, a devastating boll-weevil attack on the cotton crop made farming more difficult in the South. The North was promising wages up to ten times what could be made in the South. African Americans themselves cite social reasons for their migration. The North promised good schools for black children, as opposed to Southern schools which ran for only six weeks if the students were black. The North also promised “safety of person and property and wider social opportunity.”

African-American men who moved to the North were all eligible voters, and were treated as such by politicians. Women still didn’t have the right to vote. Profound attention was brought to a tenth of the population who had been previously ignored.

The “Negro Migration” grew out of desperation and necessity, and laid the groundwork for the civil rights movement, followed fifty years later. In this new environment, particularly in the Harlem district of New York City, an African-American cultural movement grew and flourished into the vibrant period later known as the Harlem Renaissance.

— Caitlyn Thompson

The Harlem Renaissance

“Liberate the minds of men and ultimately you will liberate the bodies of men.” — Marcus Garvey

“Mama exhorted her children at every opportunity to ‘jump at de sun.’ We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.” — Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road, 1942

In the years following WWI, the African-American community began to celebrate its own rich, cultural heritage. The New Negro Movement, later known as the Harlem Renaissance, was an explosion of black social thought and culture from the 1920’s to the 1940’s in new communities forming in Harlem and other northern cities. By the 1920’s, Harlem had become the center of black political and cultural activity. African-Americans began to form their own networks, publications, and organizations. Organizations like the NAACP (National Association for Advancement of Colored People) were formed and individuals like W.E.B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey inspired a surge of racial pride. DuBois used the NAACP’s magazine Crisis to address the opening of black officer training schools, to promote against lynchers, and to lobby for a federal work plan for returning veterans. Garvey was a successful activist who established the Universal Negro Improvement Association to unite African-Americans with their native Africa. Garvey held many parades through Harlem with red, black, and green liberation flags flying. The colors symbolize the blood, skin, and blossoming hope of black people. African-American artistic expressions such as the upbeat and catchy rhythms of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, James P. Johnson, Billie Holliday, and Ella Fitzgerald, the poignant and culturally revealing stanzas of Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson, and the vibrant art of Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden, to name just a few, were recognized across the world as important cultural contributions to society.

In the years following WWI, the African-American community began to celebrate its own rich, cultural heritage. The New Negro Movement, later known as the Harlem Renaissance, was an explosion of black social thought and culture from the 1920’s to the 1940’s in new communities forming in Harlem and other northern cities. By the 1920’s, Harlem had become the center of black political and cultural activity. African-Americans began to form their own networks, publications, and organizations. Organizations like the NAACP (National Association for Advancement of Colored People) were formed and individuals like W.E.B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey inspired a surge of racial pride. DuBois used the NAACP’s magazine Crisis to address the opening of black officer training schools, to promote against lynchers, and to lobby for a federal work plan for returning veterans. Garvey was a successful activist who established the Universal Negro Improvement Association to unite African-Americans with their native Africa. Garvey held many parades through Harlem with red, black, and green liberation flags flying. The colors symbolize the blood, skin, and blossoming hope of black people. African-American artistic expressions such as the upbeat and catchy rhythms of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, James P. Johnson, Billie Holliday, and Ella Fitzgerald, the poignant and culturally revealing stanzas of Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson, and the vibrant art of Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden, to name just a few, were recognized across the world as important cultural contributions to society.

The Renaissance began to die off during the 1930’s. The Depression forced many of the organizations formed during the Renaissance to shift focus to economic issues. In 1935, the Harlem Riot broke out between African-Americans and white shop owners. This riot was one of the major events that destroyed the image of Harlem as a cultural and political center of black ideal.

— Rachael Brady and Stephen Sposito

Notes on De Organizer

Sharecropping

Sharecropping emerged in the southern United States shortly following the Civil War (1861-1865) and the emancipation of African-American slaves. After the war, plantation owners in the South were faced with a predicament; while they might own a sizeable parcel of land, they needed labor to farm it. The Southern economy was in such a shambles that in most cases the plantation owners could hardly afford to buy seed and farm implements, let alone pay hired hands outright. Many former slaves were also in a predicament, not having the benefit of education or any experience beyond farming with which to secure a job. Sharecropping – the working of a piece of land by a tenant farmer, who compensates the landowner with a portion of the crops or revenue (usually half) – developed as a sort of compromise. Landowners scraped together enough money to supply seed, farm implements, and basic provisions for the tenant farmers (which included poor whites as well as former slaves) who, inexchange, worked a portion of the land. When the crops sold, the sharecroppers and landowners split the profit, with the sharecroppers reimbursing the landowners for their personal living expenses out of their share. In principle, the system was fair enough, but in practice, it was subject to many problems, including the unpredictably of the crops, fluctuating crop prices, and considerable abuses by the landowners. Many of the plantations had their own company store at which the sharecroppers were required to buy supplies and provisions – on credit, and sometimes at highly inflated prices. Often the sharecroppers would end up in the negative once they paid off the year’s debts and interest. Perpetual debt to the landowners left the sharecroppers in a position akin to slavery – they worked their way deeper and deeper into debt, with no legal means of escape. Illiteracy prevented black sharecroppers from checking the accuracy of the bookkeeping. White sharecroppers, on the other hand, usually had a basic education, and were able to challenge the landowners. This sometimes resulted in white sharecroppers being dismissed and replaced by African-Americans who would not question the accounts, which worsened race relations in the South. The troubled situation was unintentionally exacerbated during the Depression by the New Deal, which actually paid landowners to leave parts of their land fallow in order to decrease supply and increase crop prices. This program, in combination with improving farm technology, left hundreds of thousands of sharecroppers without work, helping to prompt the rise of unions in the 1930’s.

Sharecropping emerged in the southern United States shortly following the Civil War (1861-1865) and the emancipation of African-American slaves. After the war, plantation owners in the South were faced with a predicament; while they might own a sizeable parcel of land, they needed labor to farm it. The Southern economy was in such a shambles that in most cases the plantation owners could hardly afford to buy seed and farm implements, let alone pay hired hands outright. Many former slaves were also in a predicament, not having the benefit of education or any experience beyond farming with which to secure a job. Sharecropping – the working of a piece of land by a tenant farmer, who compensates the landowner with a portion of the crops or revenue (usually half) – developed as a sort of compromise. Landowners scraped together enough money to supply seed, farm implements, and basic provisions for the tenant farmers (which included poor whites as well as former slaves) who, inexchange, worked a portion of the land. When the crops sold, the sharecroppers and landowners split the profit, with the sharecroppers reimbursing the landowners for their personal living expenses out of their share. In principle, the system was fair enough, but in practice, it was subject to many problems, including the unpredictably of the crops, fluctuating crop prices, and considerable abuses by the landowners. Many of the plantations had their own company store at which the sharecroppers were required to buy supplies and provisions – on credit, and sometimes at highly inflated prices. Often the sharecroppers would end up in the negative once they paid off the year’s debts and interest. Perpetual debt to the landowners left the sharecroppers in a position akin to slavery – they worked their way deeper and deeper into debt, with no legal means of escape. Illiteracy prevented black sharecroppers from checking the accuracy of the bookkeeping. White sharecroppers, on the other hand, usually had a basic education, and were able to challenge the landowners. This sometimes resulted in white sharecroppers being dismissed and replaced by African-Americans who would not question the accounts, which worsened race relations in the South. The troubled situation was unintentionally exacerbated during the Depression by the New Deal, which actually paid landowners to leave parts of their land fallow in order to decrease supply and increase crop prices. This program, in combination with improving farm technology, left hundreds of thousands of sharecroppers without work, helping to prompt the rise of unions in the 1930’s.

— Lucretia Fleury

Sharecroppers’ Unions

The two major sharecropping unions formed were The Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union (STFU) and The Share Cropper’s Union (SCU). These two unions were mostly headed by black and white Ministers and largely backed by the Socialist and Communist Parties respectively. The STFU marked a revolution in unionization by allowing both black and white members. Slowly the troubled plight of sharecroppers became recognized as a national problem when sharecroppers went on strike in 1935 and 1936. Union leaders made a plea to Eleanor Roosevelt for reform, and several prominent white union supporters were attacked. Unions faced enormous opposition. When landowners discovered their tenant farmers joining unions they would attempt to deter them by cutting pay, threatening them, and murdering leaders.

Both the STFU and the SCU were very short lived due to conflicting ideals within the unions and the discrimination they faced from the political systems. Unfortunately the unions existed only long enough to change minds, and not legislation.

— Gina Rattan

About the Reconstruction of the Operas

Perhaps encouraged by Gershwin’s 1936 Porgy and Bess, James P. Johnson wrote two one-act operas in the late 1930s. The better known of the two is De Organizer, with a libretto by novelist, poet, and columnist Langston Hughes, designed from the outset to be sung. The work is about sharecroppers organizing themselves into union. With eight soloists, chorus, and orchestra, it is a large-scaled and tuneful score. In May, 1941, the opera had its only verified complete performance, in Carnegie Hall, and then it vanished. Except for a three-minute recording of the opera’s “Hungry Blues,” the opera was thought totally lost.

In 1997 I found a partial score of De Organizer in the UM’s Eva Jessye Collection. This unusual manuscript score contained only the sung notes of the opera. Using this score and material supplied by Barry Glover, Sr., Johnson’s grandson and head of the James P. Johnson Foundation for Music and the Arts, I restored the opera. In 2002, with musical forces from the UM School of Music, De Organizer was given two unstaged concert performances.

Examining James P. Johnson manuscripts and papers in the care of their curator, Barry Glover, I was initially focused on De Organizer. But as I looked through the material, I found music from The Dreamy Kid, Johnson’s first opera, written in 1937. Having to stay focused on the large task of finding the scattered, usually unlabeled, fragments of De Organizer, I had little time to examine The Dreamy Kid.

Once I had completed restoration of De Organizer, I asked Glover’s permission to work on Dreamy. The opera is a setting of the 1918 play of the same name by Eugene O’Neill. Setting the play virtually word for word, Johnson froze the action at four points for three arias and a duet by the play’s four characters.

A first draft of the entire opera, a score with the voice roles and a two-stave version of the instrumental music exists. Sketchy at points, it contains several notes to himself by Johnson about projected alterations – “transpose to E major” – and orchestration details, with less and less specificity as the piece goes on. Some measures are either left blank – “add eight bars for stage action” – or left with only a sketch of melody. A second draft, completed for only the first half of the entire work’s 1800 measures, carries out these compositional plans. In addition, Johnson completed an orchestration of the first 150 measures of the piece, an overture, a before-the-curtain aria, and the very beginning of the action. Apart from two arias from the opera performed in a concert devoted completely to Johnson’s concert works in 1942, the opera has remained unperformed.

Johnson had hoped to present these rather different one-act operas paired in a single evening. We will realize Johnson’s hope with a premier performance of The Dreamy Kid and the fully staged performance of De Organizer.

— Professor James Dapogny

Sponsors

The 125th Anniversary season is made possible in part by a generous gift from Will and Jeanne Caldwell.

Jackie O is sponsored in part by a generous grant from the Institute for the Humanities and the Modern Greek Program. Special thanks to Senior Vice Provost Lester Monts for his assistance.

The Dreamy Kid is presented by special arrangement with the James P. Johnson Foundation for Music and the Arts, and the Estate of James P. Johnson.

De Organizer is presented by special arrangement with the James P. Johnson Foundation for Music and the Arts, the Estate of James P. Johnson, and Harold Ober Associates, agent for the Estate of Langston Hughes.

The School of Music, Theatre & Dance acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.