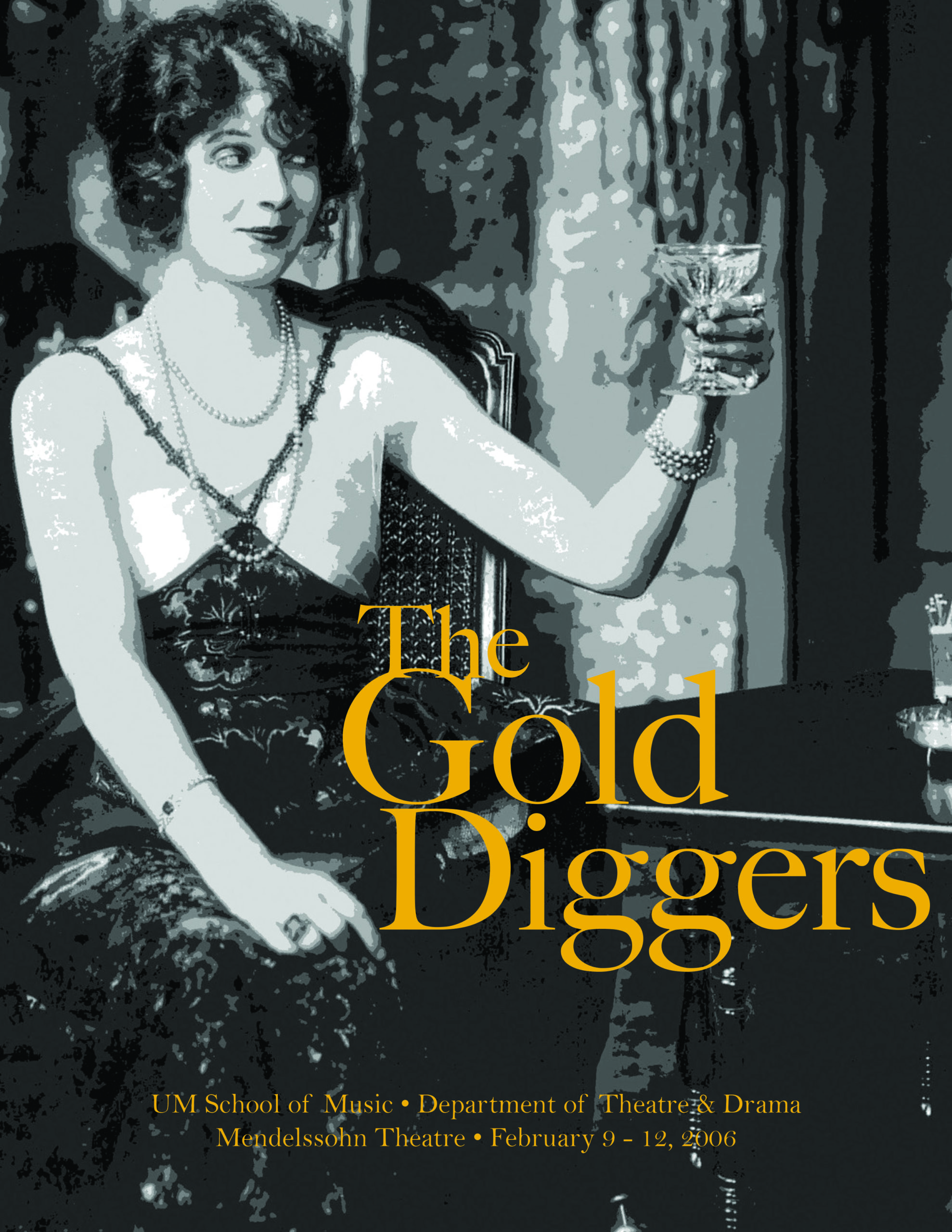

The Gold Diggers

By Avery Hopwood

Department of Theatre & Drama

February 9-12, 2006 • Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre

In the years before unions enabled chorus girls to earn a living wage, rich businessmen sought the company of these beautiful and lively performers. Many believed that the men preyed upon the women by offering them expensive gifts in return for certain favors. In The Gold Diggers, Avery Hopwood turns the tables in true comic fashion by making the women a lot more predatory and wily than the men. “Why shouldn’t we girls capitalize on what nature has given us? We’ve got to live – and what’s more, we’ve made up our minds to live darned well!” One wonders who is exploiting whom in this situation comedy where young and middle aged, single and married, innocent and world-wise, look for love, or at least a comfortable life.

The Neil Simon of his day, Avery Hopwood was one of the most financially successful – and funniest – playwrights of the 1920s. The Gold Diggers, written in 1919, was a big hit, spawned numerous movie adaptations, and forever coined the phrase ‘gold digger’ as part of the English vernacular. Avery Hopwood’s legacy includes UM’s Hopwood Awards, a program established to encourage creative writers. As part of the Award’s 75th Anniversary, the Department of Theatre and Drama is thrilled to present this rarely performed comic gem featuring live music by Phil Ogilvie’s Rhythm Kings, musical direction by James Dapogny.

Artistic Staff

Director: Philip Kerr

Assistant Director: Sarah-Jane Gwillim

Music Director: James Dapogny

Scenic Designer: Gary Decker

Costume Designer: Zelma H. Weisfeld

Lighting Designer: Stephen Siercks

Choreographer: Erin Farrell

Wig Designer: Alex Michaels

Stage Manager: Kathryn McKee

Cast

Jerry Lamar, chorus girl and model: Alexandra Odell

Violet Dayne, chorus girl: Lauren Lopez

Mabel Munroe, chorus girl: Rachael Soglin

Trixie Andrews, chorus girl: Kirsten Mara Benjamin

Gypsy Montrose, chorus girl: Sara Greenfield

Dolly Baxter, chorus girl: Ali Kresch

Topsy St. John, chorus girl: Rebecca Schwartzstein

Eleanor Montgomery, chorus girl: Anna Heinl

Stephen Lee, businessman, Wally’s uncle: Adam H. Caplan

Wally Saunders, Stephen’s nephew: Nick Lang

James Blake, lawyer, friend of Stephen: Daniel Strauss

Barney Barnett, businessman: Eric James Schinzer

Cissie Gray, former stage star: Erin Farrell

Mrs. Lamar, Jerry’s mother: Karenanna Creps

Sadie, Jerry’s domestic help: Mikala Bierma

Freddie Turner: Matthew Smith

Fenton Jessup: Andy Neuenschwander

Tommy Newton: Jeff Blim

Marty Woods: Adam Miller-Batteau

Sponsors

The 125th Anniversary season is made possible in part by a generous gift from Will and Jeanne Caldwell.

The School of Music acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Resources

About The Gold Diggers

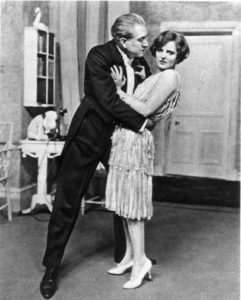

The first show to open the Lyceum Theatre after the Actors’ Equity strike of 1919 was David Belasco’s production of Avery Hopwood’s newest and brightest comedy, The Gold Diggers. Hopwood had gotten the idea for his latest work almost a year before while sitting in the Ritz in New York with a charming, and “apparently authentic blonde,” Kay Laurel. As the two sat waiting for a mutual friend, Miss Laurel called out to a girlfriend who had just entered the bar, “Hello, Gold Digger.” “Gold Digger?” asked Hopwood. “Yes,” responded Miss Laurel, a quite heavenly smile on her lips and a dancing little devil in her eyes, “That’s what we call ourselves! You men capitalize on your brains, or your business ability, or your legal minds – or whatever other darned thing you happen to have! So why shouldn’t we girls capitalize what nature has given us – our good looks and our ability to please and entertain men? You men don’t give something for nothing – why should we? It’s an art to amuse men – to thrill them, to fascinate them, to make them happy. Why shouldn’t we be paid for it? We’ve got to live – and what’s more, we’ve made up our minds to live darned well!”

Jotting the idea down, as he often did, on his clean, starched cuffs, Hopwood later filed the comments for future development in his “fat black note-book,” otherwise known as his “family Bible.” It wasn’t until David Belasco had summoned him to discuss possible ideas for a young actress under his management [Ina Claire] whom he intended to promote as a “star” that the idea actually began to take shape. After skimming several possibilities in his notebook, Hopwood came upon the gold diggers scribble. “I’ll take it!” barked Belasco, “Go ahead and write that play – I’ll take it!”

By all accounts, Hopwood worked on the scenario and dialogue of the play for five weeks; and in the end, with the benefit of “D.B.’s unfailing interest and sympathy, and … his rich suggestfulness,” he succeeded in giving the American theater a comedy that would eventually serve as the generator of numerous movie musical spectaculars: The Gold Diggers. Now a popularized slang term found even in the dictionary, it’s hard to think there was a time when Belasco’s advance men advised him to change the title because audiences expected a play about the forty-niners!

Luxuriously produced in a one-piece set that captured the “realistic” atmosphere of the typical chorus girl’s habitat in the “Eighties, between Broadway and Riverside,” The Gold Diggers presented audiences with beautiful women, the latest in Bendel fashions, and the most breathtaking sunlight yet seen on the American stage. Belasco’s new $80,000 lighting system created a “strange exotic atmosphere” that spread through the theatre “like a perilously fragrant vapor released from a magic urn.”

Everything about the production had been designed to make it an entertainment of immense theatrical appeal. The capacity audiences seemed to grow even larger as the play moved into 1920. When Prohibition struck on January 18, the crowds at the Lyceum began to revel in the champagne atmosphere that surrounded the performance. Before long, it was billed as the most “sparkling” comedy in town; and by May, Variety was reporting on the play’s remarkable ability to draw “repeaters.” Insiders speculated that the show would run well into the next season due, in part, to the large number of musical comedy performers in the cast who had developed a loyal following. This following and Claire’s smart comedic style did, indeed, keep the play on the boards for 720 performances (two years) — at a time when 100 performances was deemed a financial success. A successful tour followed. Had he lived to hear the lyrics, Hopwood couldn’t have helped but “Tip-Toe Through the Tulips” (from the Warner Brothers Gold Diggers of Broadway, 1929), and nod in cynical agreement to the lead lyric from Gold Diggers of 1933: “We’re In the Money.” After all, the idea he got from his “apparently authentic blonde” friend Kay Laurel earned him at least $236,000 in royalties in its initial run. The Gold Diggers made its last professional appearance on the Broadway Television Theatre, December 29, 1952.

— Excerpted and adapted from Avery Hopwood His Life and Plays by Jack F. Sharrar. Used by permission.

About Avery Hopwood

Avery Hopwood was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1884; he was graduated from the University of Michigan, Phi Beta Kappa, in 1905. Thereafter he went to New York. Although known as the “playboy playwright,” he had a productive career; he was the author or coauthor of thirty-three plays. He wrote one novel also. In her memoir, What Is Remembered, Alice B. Toklas describes Hopwood and Carl Van Vechten as having jointly “created modern New York. They changed everything to their way of seeing and doing. It became as gay, irresponsible and brilliant as they were.”

Hopwood recalled his own original impetus, and why he began work on his first play, Clothes:

“An intense admiration for the theater, a fondness for writing, and the ambition to make money, contrived to pave the way for my career as a dramatist; but the influence that focused my efforts was an article written by Louis V. De Foe, that appeared in the Michigan Alumnus, when I was a student at the University of Michigan. “The Call of the Playwright” was its title, and in it Mr. De Foe told of the fabulous sums that dramatists had made; the more I thought about it, the more determined I became to try my luck in this field.”

He did, and his gamble paid off. By 1920, Hopwood could claim four shows running simultaneously on Broadway, and two years later the New York Times described him as “almost unquestionably the richest of all playwrights.” He celebrated often, lavishly, and then his luck ran out. In his last years he spent little time in America; to this card-carrying member of “the lost generation,” both artistic and personal freedom seemed constrained at home. He died at Juan-les-Pins, swimming, in 1928. There were suspicions: he had been drunk, he had been murdered, he went swimming too soon after lunch. The coroner’s verdict, however, was coronary occlusion.

Hopwood’s legacy, if not his writing, endures. “What is remembered” at present are the awards in his name. Under the terms of his will, and after the death of his mother, one-fifth of Hopwood’s estate was to be left to the Regents of the University of Michigan. The will stipulates that prizes be awarded to students “who perform the best creative work in the fields of dramatic writing, fiction, poetry, and the essay.”

“Time hath, my lord, a wallet at his back, wherein he puts alms for oblivion.” So wrote a greater playwright than the one who is our subject here. As Shakespeare reminds us in Troilus and Cressida, oblivion of one sort or another is the necessary fool of time, and none of us escapes that necessary end. Still, some oblivions are more absolute than others, and some provisions against it may in fact endure. The reputation of Avery Hopwood now rests almost entirely on the “alms” he provided to his alma mater, and to the program thereby established in order to encourage young writers. In each of the categories adduced above the list of winners is long, and the “wallet at his back” has proved to be capacious. Since 1931 we have awarded more than two million dollars in the name of the forgotten author of Getting Gertie’s Garter, Nobody’s Widow, Fair and Warmer, and Ladies’ Night (In a Turkish Bath).

The fiscal imperatives of cost-effective entertainment have changed at least as much as has the public’s taste for sexual explicitness; characters who “come out of the closet” have always played a part in bedroom farce. Too, the mores of the theatre-going public have been irrevocably altered by technological advance. So one of the ways to read this playwright is in terms of the change of venue where such talents as his are deployed; “the Neil Simon of his day,” as his biographer describes him, was “skating on thin ice.” What aroused the censors and raised eyebrows or temperatures at the time would seem like stale coquettishness a few years later on. Playgoers in the teens and twenties went to the show in Manhattan or to the touring companies for laughs and thrills; now a flick of the TV or VCR switch produces such performances at home. The degree of license in licentiousness has enlarged, no doubt, and verbal titillation and erotic titivation have certainly increased. But they are part and parcel of a constant enterprise; take a pretty young person and dress him or her scantily and an audience will ogle and, for the privilege, pay. Hopwood understood this then; he would understand it now; he would now as then succeed.

The Wheel of Fortune turns. The pendulum swings, then swings back. It’s possible to argue, even, that theatre is in its nature ephemeral: since performance must be evanescent, such fleetingness is part of the drama itself. Yet a man with four productions at once on The Great White Way need not go so completely “dark” within the century, and there’s nothing shameful about the appellation “minor.” If only as a cautionary tale about talent ill-attended to and the transient nature of success, the life of Avery Hopwood should be better understood and the work more widely known.

— Nicholas Delbanco, Chair, Hopwood Awards