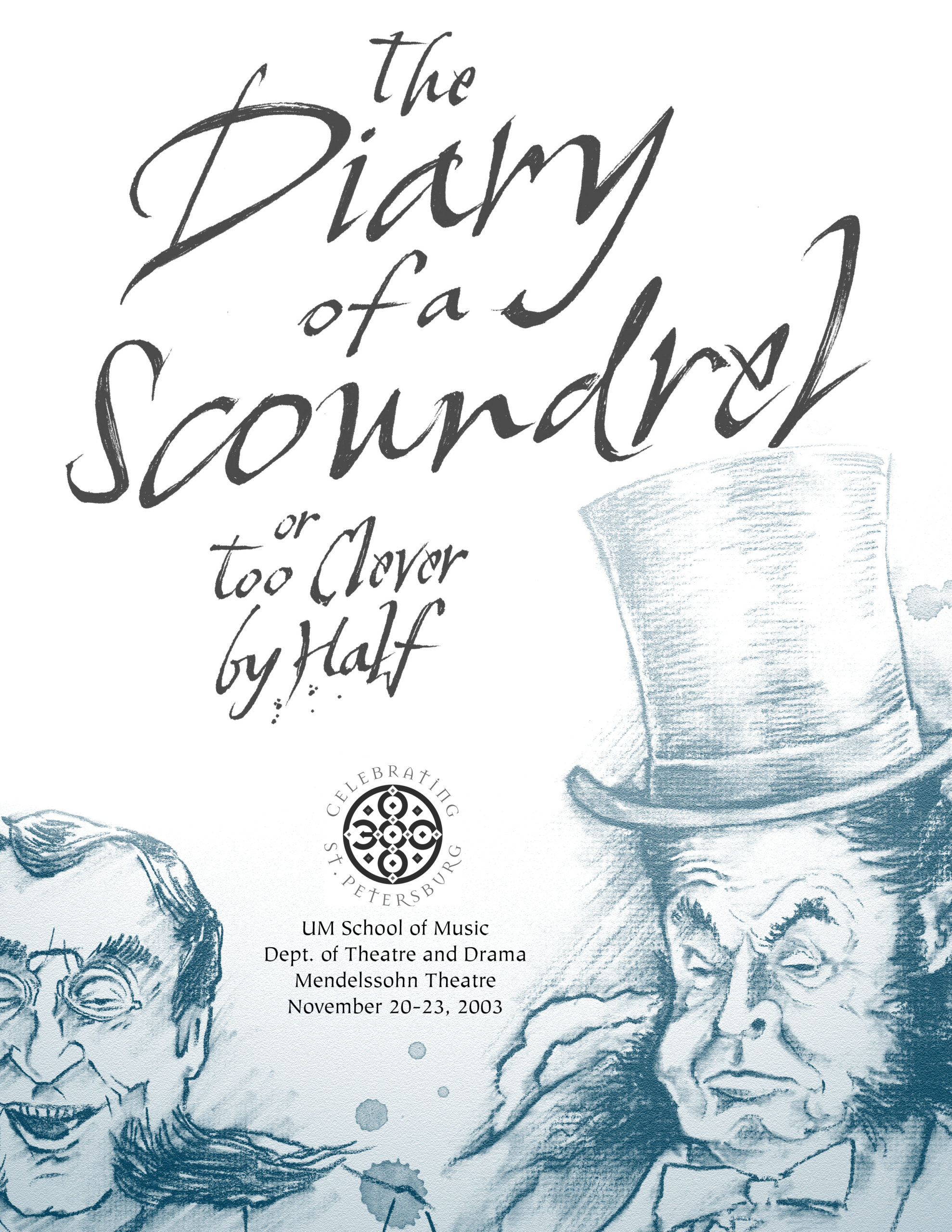

The Diary of a Scoundrel or Too Clever by Half

by Alexander Ostrovsky

Translated by Stephen Mulrine

Department of Theatre & Drama

November 20-23, 2003 • Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre

The Diary of a Scoundrel is presented as a part of UM’s “Celebrating St. Petersburg” festival. This University-wide festival commemorates the 300th anniversary of a city that has been extraordinarily influential on Western culture.

The Diary of a Scoundrel is a tale of one man’s mission to finagle his way into upper-class society, no matter what it takes. Set in 1874, this social comedy follows Glumov, a poor, young bachelor, in his quest to marry a wealthy woman and acquire a simple, yet lucrative job. To reach these goals, Glumov will lie, flatter, and cater to the vanities of the wealthy. Unable to contain his disgust with his victims, Glumov decides to relieve his unvoiced satirical comments by recording his schemes in a diary. Accidentally, the diary is discovered by some of Glumov’s wealthy acquaintances, which could mean the end of his scheme.

The Diary of a Scoundrel makes a social comment on how far an individual will go to gain wealth and power, but does so in an enjoyable, comic manner. Says Director Malcom Tulip, “The interplay between comedy and drama in this piece is exquisite.” Glumov, the play’s scoundrel, has made his living writing epigrams and making caricatures of his victims. According to Tulip, “We’ve highlighted those qualities in each character through costumes and acting by depicting people and situations as ‘larger than life.'”

Artistic Staff

Director: Malcolm Tulip

Scenic Designer: Gary Decker

Costume Designer: Elisabeth Tholen

Lighting Designer: Michelle Epel Sherry

Wig Designer: Sarah A. Opstad

Assistant Director: D. Ross

Dramaturg: John Hill

Stage Manager: Erin A. Whipkey

Cast

Glumov, a young man: J. Theo Klose

Glafira, his mother: Leigh Feldpausch

Kurchaev, a hussar: Brad Fraizer

Golutvin, a young man without a job: Zach Dorff

Andrei, Mamaev’s servant: Nathan Ciccolo

Mamaev, a wealthy gentleman: Brian Luskey

Manefa, a fortune-teller: Kathryn Thomas

Krutitsky, an old and important person: Nathan Petts

Kleopatra, Mamaev’s wife: Erin Farrell

Masha, Turusina’s niece: Lauren Roberts

Turusina, a wealthy widow: JoAnna Spanos

Grigory, Turusina’s servant: Kevin Kuczek

Gorodulin, a young and important person: Adam H. Caplan

First Hanger-On: Stephanie Sullivan

Second Hanger-On: Beckah Gluckstein

Footman, Krutitsky’s servant: Daniel Strauss

Sponsors

The School of Music acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Resources

Dramaturg’s Notes

Aleksander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky was Russia’s most prolific dramatist. Three of his plays are included in the national school curriculum, and in Moscow alone, productions of his dramas are part of the repertory of dozens of theaters. While Soviet generations enjoyed their Ostrovsky served up as social critic and sympathetic to the revolutionary struggle, even with all the recent changes in ideas and values in today’s Russia, there is no sign that the dramatist’s popularity is waning. Part of his success must be due to his brilliant, authentic dialogue: the ability to portray nuances of different economic and social groups as well as a flair for all that is most colorful and striking in spoken Russian. One of the myths about Ostrovsky, however, is that his dramatic gift does not transcend the narrow appeal to his fellow Russians. While something is lost in translation, there is much that remains in his plays to challenge people on both sides of the footlights even today, even far from Moscow. Another myth is that all of Ostrovskyís almost fifty plays are about the Moscow merchant class. The playwright did, indeed, conjure that parochial milieu that formed at the junction of nouveau-riche aspirations and salt-of-the-earth sensibility in a number of works, especially in his early period. Liberal critic Dobroliubov lionized the early Ostrovsky in seminal essays like “The Dark Kingdom,” a metaphor for the closed, tyrannical merchant world. Turgenev called Ostrovsky the “Shakespeare of the merchant class.” In the West, this conventional wisdom was challenged even less frequently than in Russia. His most famous play here, The Storm, has to do with merchants, albeit in a provincial city and not Moscow. In fact, though, the slice of life to be found in Ostrovsky’s plays is wider and deeper than just the merchant layer. He wrote historical dramas, created a verse play based on folk tales of the Snow Maiden, portrayed the life of provincial actors, explored other aspects of provincial life, and penned many dramas centered in Moscow that have little or nothing to do with the merchant class, such as the satirical look at the aristocracy: The Diary of a Scoundrel.

Aleksander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky was Russia’s most prolific dramatist. Three of his plays are included in the national school curriculum, and in Moscow alone, productions of his dramas are part of the repertory of dozens of theaters. While Soviet generations enjoyed their Ostrovsky served up as social critic and sympathetic to the revolutionary struggle, even with all the recent changes in ideas and values in today’s Russia, there is no sign that the dramatist’s popularity is waning. Part of his success must be due to his brilliant, authentic dialogue: the ability to portray nuances of different economic and social groups as well as a flair for all that is most colorful and striking in spoken Russian. One of the myths about Ostrovsky, however, is that his dramatic gift does not transcend the narrow appeal to his fellow Russians. While something is lost in translation, there is much that remains in his plays to challenge people on both sides of the footlights even today, even far from Moscow. Another myth is that all of Ostrovskyís almost fifty plays are about the Moscow merchant class. The playwright did, indeed, conjure that parochial milieu that formed at the junction of nouveau-riche aspirations and salt-of-the-earth sensibility in a number of works, especially in his early period. Liberal critic Dobroliubov lionized the early Ostrovsky in seminal essays like “The Dark Kingdom,” a metaphor for the closed, tyrannical merchant world. Turgenev called Ostrovsky the “Shakespeare of the merchant class.” In the West, this conventional wisdom was challenged even less frequently than in Russia. His most famous play here, The Storm, has to do with merchants, albeit in a provincial city and not Moscow. In fact, though, the slice of life to be found in Ostrovsky’s plays is wider and deeper than just the merchant layer. He wrote historical dramas, created a verse play based on folk tales of the Snow Maiden, portrayed the life of provincial actors, explored other aspects of provincial life, and penned many dramas centered in Moscow that have little or nothing to do with the merchant class, such as the satirical look at the aristocracy: The Diary of a Scoundrel.

The Diary of a Scoundrel marks a clear break in Ostrovsky’s output from the genre pictures of his early career. Experiencing something of a crisis in the mid 1860s, ideas for plays about contemporary life and current social problems dried up. He tried to keep the creative fires burning by composing historical plays about the distant 17th century and writing opera libretti, as well as translating Italian comedies. At one point he even considered quitting the theater altogether. When Ostrovsky the social critic was ready to return, he found that the world of his early plays was gone for good. There had been a sea change in Russian life. The Emancipation Manifesto of 1861 was the pivot point of 19th century Russian history. Everything that came before it – from the Decembrist’s hopes to transform Russia based on progressive, Western European ideas that young, aristocrat officers had soaked up in Parisian cafes in 1815 with the defeat of Napoleon, to the reaction and stagnation that followed under Nicholas I – everything was a prelude to freeing the serfs. And all that followed must equally be seen in the light of the abolition of serfdom. Masters no less than slaves had their lives turned upside down. It was a painful time for many aristocrats. While some looked back with nostalgia and hatched plans for counter-reform, others felt the way the wind was blowing and jumped onto the progressive bandwagon. Amid this uncertainty and transition, an ambitious young man could still get ahead, if he planned things carefully and ingratiated himself with the right people…

The title of the play, a Russian proverb, has been variously translated: Too Clever By Half, Even a Wise Man Stumbles, Even Wise Men Err, Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man, No Man is Wise at All Times, The Diary of a Scoundrel, Glumov’s Diary, and The Scoundrel. Perhaps the closest match in spirit if not in letter can be found in an old American folk saying – “Every man has a fool up his sleeve.”

— John Hill