Michigan Muse Winter 2025 > Before the Curtain Rises: The Many Elements of an SMTD Production

Before the Curtain Rises: The Many Elements of an SMTD Production

By Judy Galens

On a warm spring night, theatregoers file into the Power Center for the Performing Arts, finding their seats, chatting with friends, thumbing through the program. Musicians in the orchestra pit warm up, performers backstage put the finishing touches on their costumes and makeup. It’s opening night, and an excited buzz fills the theatre as the lights go down.

Opening night marks an exciting beginning, but it also represents the culmination of months of creative exploration, hard work, problem-solving, and collaboration, with hundreds of students, faculty, and staff coming together to produce a professional-caliber show on a university-level budget.

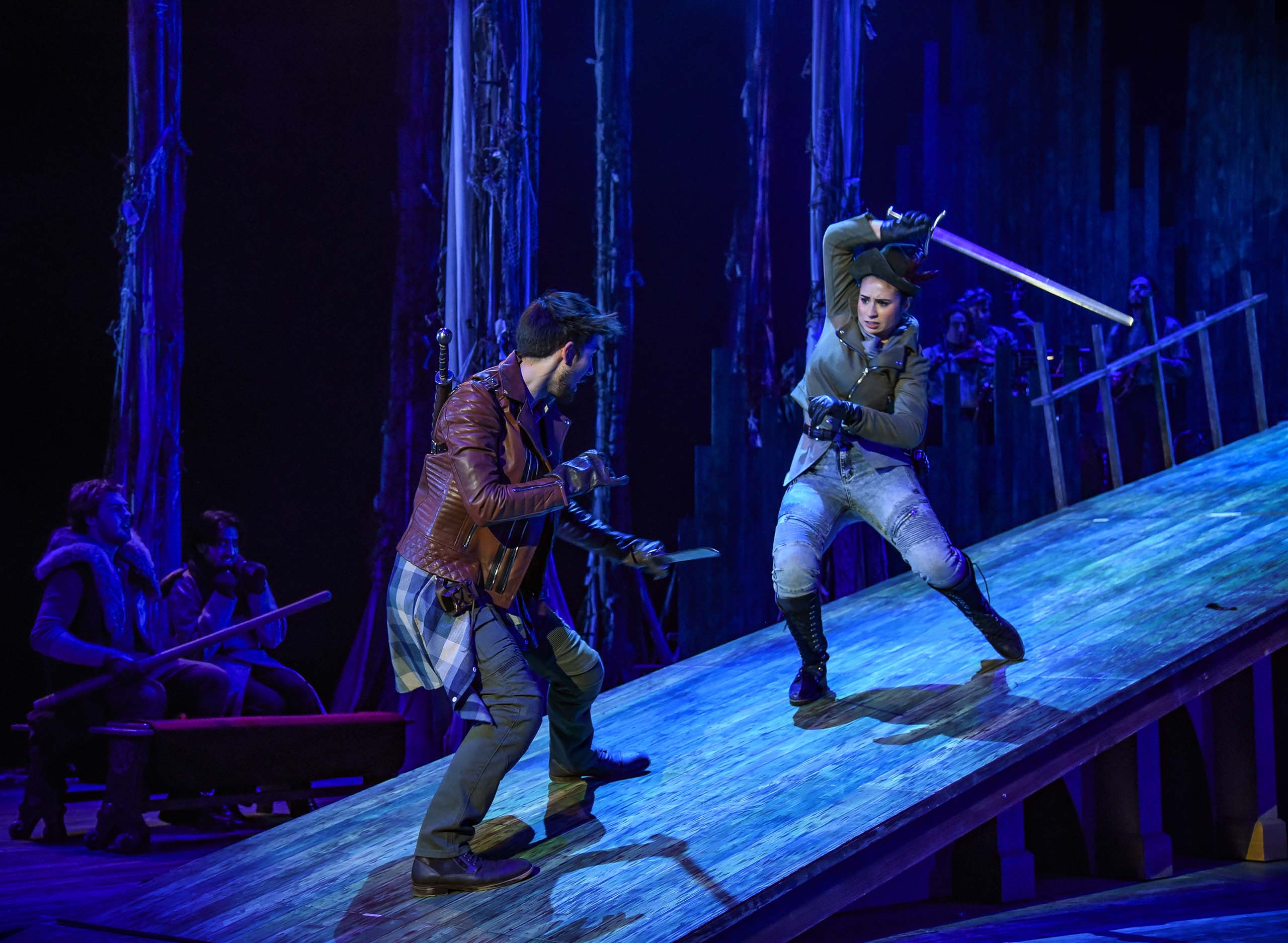

The opera Orpheus in the Underworld, November 2023. Photo: Peter Smith

A Balancing Act: Selecting Productions for Upcoming Seasons

The journey to opening night begins several months, sometimes more than a year, earlier, when each producing department works through a complex, brain-teasing, multi-dimensional puzzle: selecting the productions for the upcoming season. This process varies by department, though each must balance a similar set of considerations.

At the top of the list is the repertoire’s value in terms of educating students and preparing them to compete – as SMTD students do with great success after graduation – on Broadway, on national tours, in opera and dance companies all over the world, and in film and television. Cynthia Kortman Westphal, Arthur and Martha Hearron Endowed Professor of Musical Theatre and chair of the department, explained the curricular goals for her department: “We aim to offer a well-rounded selection of productions that thoughtfully balances genres, styles, and stories, from classics to contemporary works, from dance-heavy shows to those with rich vocal scores, spanning comedy, drama, and everything in between.” For opera, the process involves looking at 400 years’ worth of repertoire and offering students a broad selection of opportunities. “We feel an obligation to give opportunities for students to sample across that entire tradition,” said Kirk Severtson, professor of music and opera coach and conductor. “We seek to cover a diversity of repertoire across centuries, across languages and performance practice periods.” Christianne Myers, Claribel Baird Halstead Collegiate Professor of Theatre & Drama, summed up her view on the balancing act that is season selection: “Not only are we providing a variety of roles for students, but we are also amplifying a balanced range of voices, in terms of style, culture, new work versus old work, canonical work versus newer, maybe more innovative, work.”

The producing departments also consider the works that will allow the strengths of their faculty and students to shine. For example, Myers pointed out that shows like The Heart of Robin Hood and Julius Caesar enabled the department to capitalize on its substantial skill in teaching stage combat: “We have the expertise to do that well and safely, and it’s a learning opportunity.” For the opera faculty, the challenge of selecting upcoming works has everything to do with the voices of their current students. “We have to match exactly the perfect piece for the students that we know we have,” Severtson said. He noted that the process is complicated because each opera production double-casts its major roles, so “if an opera role has an unusual demand, and we have a person who has that particular talent and is a great match, we need to make sure we have a second singer who can also do that.” Westphal summed up the intent to choose works “that will challenge our students artistically and academically and reflect and celebrate the rich diversity within the department.”

Choosing the next season’s productions also involves extensive collaboration within and sometimes across departments, with many voices weighing in on which works should be selected. “It’s very much an interconnected puzzle,” said Catherine Walker, professor and associate chair of musical theatre. For theatre & drama, the selection process changed in 2022 with the advent of the “Season Selection Advisory” course, which was devised in large part as a response to students’ requests for greater input on and transparency with the selection process. It begins with a faculty-provided list of plays to consider as well as a departmental survey; throughout the semester, students read and research all of the plays, ultimately pitching a “short list” of proposed works that the faculty will further winnow down.

Practical considerations must also be weighed, including whether a production will be available, and if it is, what the cost would be to license and produce it. This is where University Productions comes in. Also known as UProd, SMTD’s producing arm manages nine fully staged and ticketed productions each academic year for the Departments of Dance, Musical Theatre, Theatre & Drama, and Voice & Opera (UProd also manages campus performance venues for the entire university community). Among many other tasks, UProd handles the licensing process, the budgets, and the design process. As each department comes up with its production wish list, the UProd staff – led by its director, Jeffrey Kuras – begin inquiring about the production’s availability and licensing cost. The availability part can be tricky. SMTD competes with professional touring companies and Broadway productions to obtain licenses for theatrical repertoire; concerned about saturating the market, rights holders will not grant a license to produce any work recently, currently, or soon to be on Broadway or a national tour. When selecting shows for the 2024–25 musical theatre season, the department had to reconfigure its plans several times due to licensing issues.

Woven throughout these complicated and sometimes conflicting considerations is the question of audience appeal. Having an audience show up and engage with the performers and the work is an essential aspect of live performance. The presence and participation of audiences for each performance does more than boost morale; it plays a vital role in the students’ training.

Putting Together the Creative Team

Almost from the moment the productions are decided on, the process of bringing that work to the stage kicks into gear on multiple fronts. Rehearsal spaces are reserved – no easy task given that so many productions and ensembles across the school are jockeying for a finite number of rehearsal halls. Discussions begin between the director of each production and UProd about the scope of the show – how many scenic locations they envision, the size of the cast, whether there’s a need for video projections, and so on – to get a sense of what’s feasible and how the budget will be allocated. The rest of the creative team begins to come together, which could include (depending on the type of performance) a conductor, music director, choreographer, production stage manager, and scenic, costume, lighting, and sound designers. Each SMTD production includes a dramaturg, who leads an exploration of the social, cultural, and historical context of the work, helping the cast and creative team to understand the work better and find contemporary relevance. Also on the team is an intimacy choreographer and cultural consultant, who helps ensure safety protocols and a culture of respect and consent for all involved.

Most of the leadership positions on the creative team are filled by SMTD faculty and by guest artists brought in to fill specific needs and enrich the curriculum. Design and production students within the Department of Theatre & Drama are involved in every production at multiple levels of responsibility. For several design and production positions, students can work their way up from assistant roles to assuming the substantial leadership responsibility of being the production stage manager, costume designer, scenic designer, or lighting designer. Myers described the process of determining placements for students, taking into account their stated preferences and career goals: “It’s an amazing puzzle. We sit down with a complex spreadsheet. We have a list of students who are ready to design, who are interested in assisting, who want to work on music, or want to work with a guest, and, like a game of Tetris, we strive to fit all the pieces together.”

Launching the Design and Production Process

The vast production universe at SMTD consists of several studios managed by UProd: the Walgreen Scene Shop and Power Center Scene Shop, which include scenic and paint studios; the Walgreen Costume Shop; the Walgreen Wig, Hair, and Makeup Studio; the Walgreen Sound Studio; the Power Center Props Shop; and the Power Center Lighting Shop. Production work at SMTD is a collaborative effort involving dozens of staff members and as many as 80 students in a given academic year; the students work in the studios for course credit, to satisfy work-study requirements, or as part-time jobs. They explore a range of roles, including charge artist (who oversees the scenic painting), first hand (who assists with construction and alteration of costumes), or master electrician (who oversees the implementation of the lighting design). The staff members in the production studios are artisans and technicians with skills such as costume construction, fabric dyeing, wig styling and fabrication, 3D printing, woodworking, welding, painting, sculpting, and many others. Other UProd staff members focus on backstage operations, front-of-house management, safety training, facilities management and booking, and so on.

Design work begins long before auditions, with designers conducting research, gathering sources of inspiration, and making preliminary sketches of their vision for the designs. They share their early sketches with the UProd team, thus beginning what can be an iterative process to develop a plan that lands somewhere between the designer’s vision and the realities of budget, time, and staff resources. “Once we get to a pretty solid design,” said Paul Hunter, production manager for UProd from 2019 to 2024, “we then share those designs with our studios to say, Okay, here’s the dream.” Then it’s a question of how much can be re-used from existing stock, how much it will cost to produce new elements, how much time it will take to realize the designs. A few months before rehearsals begin, regular production meetings begin for the whole design and production team. At these meetings, each team shares their progress and discusses logistical or other concerns as the production begins to take shape. This extensive team comprises dozens of people, and the process resembles the complexity of a professional production, with the added mandate of training and educating the students involved.

A computer rendering of the scenic design for the musical Twelfth Night, designed by Professor Kevin Judge, and the production itself, October 2024. Photo: Peter Smith

Casting the Productions

Like the processes for selecting productions and assigning students to design and production roles, the casting process is a balancing act. Directors need to see which student would best embody each role, and, as educators, they also consider the opportunities each student has had already and the ways they can help students achieve their goals and engage with a variety of roles. “Number one, it’s offering experiences,” Walker explained. “We prioritize the students’ education and consider opportunities that would benefit them at this juncture. When casting, we reflect on all aspects of their skill set and development.”

The timing and method of casting an upcoming production varies by department. Auditions for theatre & drama productions take place in the spring for fall shows, and, as Tiffany Trent, associate professor and chair of the department, explained, “students submit digital self-tapes in October for the shows in the second semester. We want to prepare students to walk in the room and to have practice with virtual submissions.” For opera productions, principal roles are also cast several months in advance, with auditions in the spring for the fall production. For the fall opera, the department holds auditions for current students and also reaches out to incoming students, inviting them to submit video auditions. Once the fall opera’s principal roles have been cast, Severtson shared, “the expectation is that students have the summer to prepare the roles.” He explained that, while abundant coaching will be available from faculty throughout the rehearsal process, students “need to have the music in their ears” when they arrive at the first rehearsal. “They need to have worked with the language, to do that important text work and learn the notes and rhythms. There is a fairly high professional standard in the opera world, and they need to be fully ready for that when they get an opera contract in the real world.”

For musical theatre’s fall production, the casting takes place at the start of the fall semester. While that timing makes for an accelerated turnaround for the cast and the costume team, the department feels it’s important to give students the experience of doing summer stock theatre or other endeavors before auditioning for the fall musical. “From a pedagogical perspective, we believe that a great deal of growth occurs during the summer months,” Walker pointed out. “Summer activities such as performing, interning in a casting office, travel, or working outside of the industry will allow students to continue their growth and development, which will in turn potentially impact their casting in the fall.”

Building a World

Once the cast is set, the pace intensifies, with the bulk of the work taking place in just a few weeks. “We hit the ground running,” Walker said of the rehearsal process, and then “the students are in rehearsal for 25 hours a week.” The production studios are a hive of activity, as sets, props, and costumes are built. Onstage performers master the material and deepen their characterizations, lighting and sound designs are finalized, and musicians immerse themselves in the score.

A sketch of Brutus’s costume for the fall 2024 production of Julius Caesar, with costume designs by theatre student Ellie Van Engen, and Katie Snowday on stage as Brutus. Photo: Peter Smith

While each of those groups works independently to a certain degree, their work becomes increasingly interwoven throughout the rehearsal process. The stage manager acts as the hub among the many spokes, ensuring an open flow of communication. After each rehearsal, the stage manager sends a rehearsal report to all involved, keeping them apprised of tweaks that need to be made to the designs and props.

For operas and musicals, one of the most significant rehearsals is the sitzprobe, or “seated rehearsal,” which is the first time the singers and the orchestra musicians come together. “It’s the most thrilling music rehearsal,” Severtson said. “It’s a chance for singers and the orchestra to listen intently to each other and interact for the first time and put it all together. After that, the costumes and the staging and everything else gets layered in. But the sitzprobe is that one time when everyone is entirely focused on the music.”

Less than a week before opening night, the creative work taking place in disparate locations all over campus comes together in the theatre for the first time. While professional theatre companies often build scenery directly onstage, the near-constant use of campus performance venues means that, at SMTD, even the most complicated set designs must be built in the shop and loaded into the theatre over the course of a day or two. Once the sets are put together onstage, tech rehearsals begin. Myers described the flurry of activity on those final days: “Lighting and sound start to work on top of the set. The team figures out the props placement and set dressing, and stage management works on tracking all the moving parts. The crew is introduced. Costumes and hair and makeup come in last, and we work on any quick costume changes that are happening during the flow of the piece. Next we have a couple of dress rehearsals, and then we open a show.”

An Ending and a Beginning

Those sitting in the audience on opening night of an SMTD production may not be thinking about the titanic effort that brought it to fruition, or the many choices the performers have made, or the intention behind every detail of the costumes, scenery, props, sound, and lighting. They may be unaware that each aspect of these complex, intricate productions is critical to the education and training of students who are striving to become successful professionals in their fields.

What audiences are aware of is that, from the moment the first notes are played or the first lines are spoken, they are completely drawn into this creative endeavor. Every element, from the obvious to the subtle, combines to immerse them in the created realm, evoking a range of emotions and perhaps even new ways of seeing the world. Audiences at SMTD productions also experience something unattainable at the Met or a Broadway theatre: the thrill of witnessing students becoming full-fledged performing artists right before their eyes.

The Collaborative Path to the Dance Department’s Flagship Show

Students in the Department of Dance have abundant opportunities to perform for audiences throughout the academic year, but the department’s flagship performance is the annual show in the Power Center for the Performing Arts, held each year in February. The Power Center show features many of the same elements as a fully produced play, musical, or opera: creative collaborations among students, faculty, guest artists, and staff, as well as costumes, scenery, lights, sound, and projections.

Planning for the Power Center show begins about a year beforehand, with the first step being selecting the choreographers who will create the four original works for the show. Faculty in the department make a list of intriguing guest artist candidates working around the world, and they poll the students as well. Ultimately, two guest artists and two faculty members are chosen, representing a range of styles and genres.

Students audition in the fall for the show being presented in the following semester. This year, the show’s artistic directors – Professors Shannon Gillen and Jillian Hopper – instituted a few changes in the audition philosophy and process. First, every eligible student now auditions for all of the choreographers (the exception is first-year students, who build experience in the First-Year Dance Company before auditioning for the Power Center show as sophomores). The choreographers work together to make the casting decisions, offering constructive feedback for each student.

The second change is that every student who auditions is cast in some capacity – either in a full role, a swing role, or an understudy role. (Swings are assigned roles that they will “swing into” for certain performances; an understudy is assigned a role or multiple roles to take over, in case of illness or injury.) Increasingly, students are also filling the role of rehearsal director – the person who runs rehearsals and, when the choreographer isn’t present, ensures that the work adheres to the original concept. Gillen described the rehearsal director as a “beautiful throughline” between “the choreographer’s vision, the work itself, and the student population that’s trying to achieve the work.” Whatever their position in the production, the goal is to give students invaluable experience that prepares them for life after graduation.

Unlike for most theatrical or operatic productions at SMTD, the dance works for the Power Center show are created after the casting process is done. “It’s not like you have a dance that already exists, and the dancers are restaging it,” Hopper explained. “It’s a brand-new concept for a dance, and the choreographers start the creation process with the students in the room.” The students, then, are not just interpreters of the choreographer’s vision; they are collaborators. Also collaborating with the choreographer are the costume, scenic, lighting, and sound designers. Because the dance show is basically four separate productions in one, the design and production process, managed and supported by UProd, must also incorporate the complex logistics of quick transitions from one work to the next.

In the end, the collaborative efforts of dozens of students, faculty, staff, and guest artists coalesce into an impressive, large-scale production that thrills audiences while providing multiple benefits for dance students: challenging their physical practice, showcasing their hard work and talent, and preparing them for life ahead as professional dance artists.

Staged Productions

Our staged productions are an essential part of what makes SMTD extraordinary. Students gain invaluable hands-on experience, honing their craft as performers, designers, and creators, and graduating well-prepared to step into their professional lives.

Where You Can Make an Impact:

The First Endowment for University Productions

As the producing arm of SMTD, University Productions creates nine ticketed shows each academic year for the Departments of Dance, Musical Theatre, Theatre & Drama, and Voice & Opera, including scenery, props, costumes, lighting, sound, and video. Establishing a first-of-its-kind endowment to support University Productions’ evolving needs will enable us to maintain our excellence while investing in the future.

Technology

While SMTD continually invests in upgraded technology to support productions, the rapid pace of technological advancement makes it extremely challenging to keep up with developments in the field. We must increase our investment in backstage and onstage technology – from projections to sound to lighting – so students can gain needed experience and drive the creative conversation in their post-college careers.

Guest Artists

While SMTD faculty possess deep and broad expertise, guest artists – from directors to choreographers to conductors to scenic and other designers – offer important support for SMTD productions, filling specific needs and providing new perspectives. The ability to incorporate guest artists means producing departments have even more options when putting together creative teams, and students are exposed to a greater variety of industry professionals. Guest artists offer important educational perspectives as well as helping to provide entry into the professional world after students graduate.