Michigan Muse Winter 2023 > A Surge in Screendance

A Surge in Screendance: A Popular SMTD Course Gets a Giant Boost in the New Dance Building

By Marilou Carlin

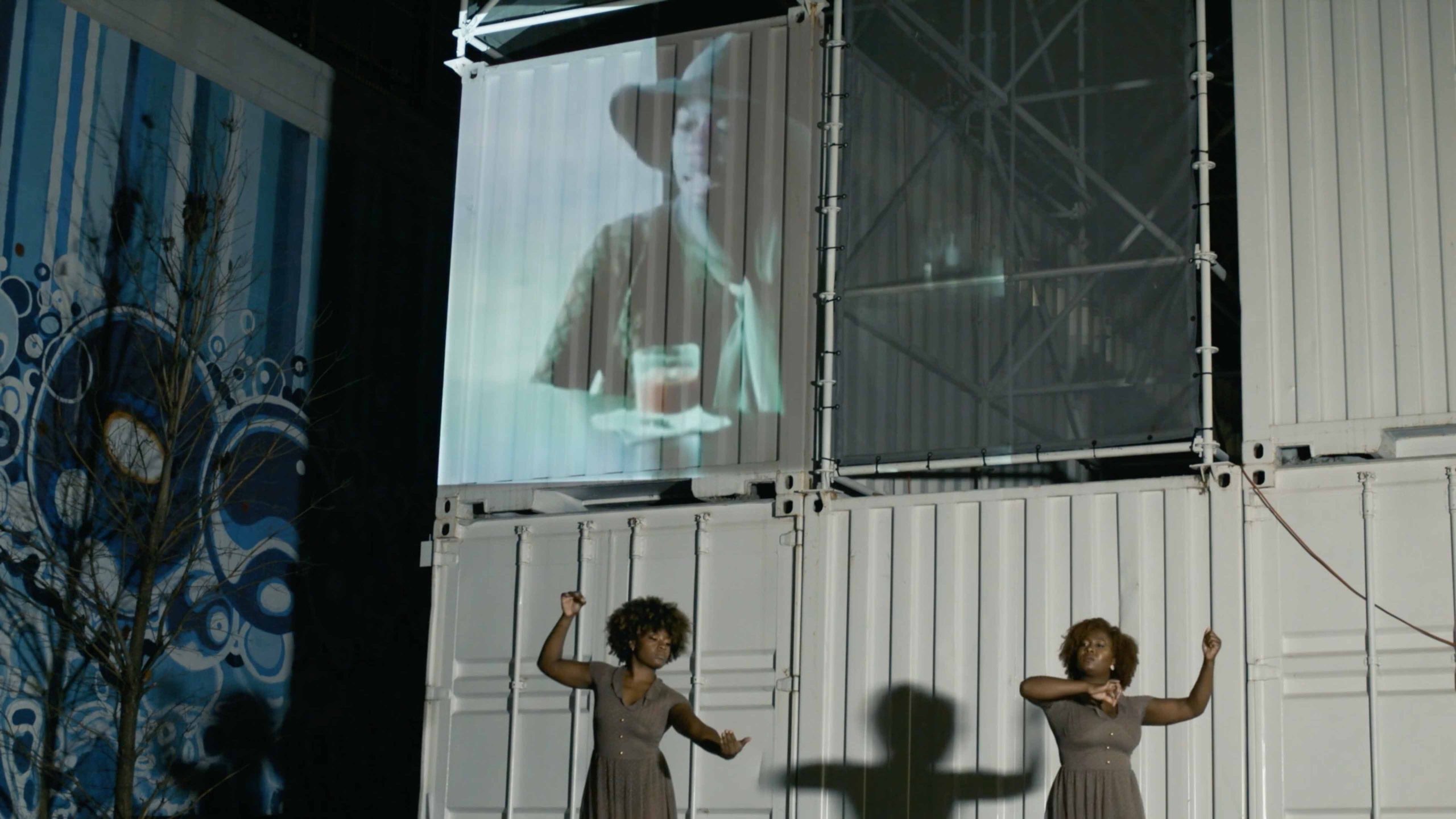

Reflect.Black.Times. by Marsae Lynette Mitchell

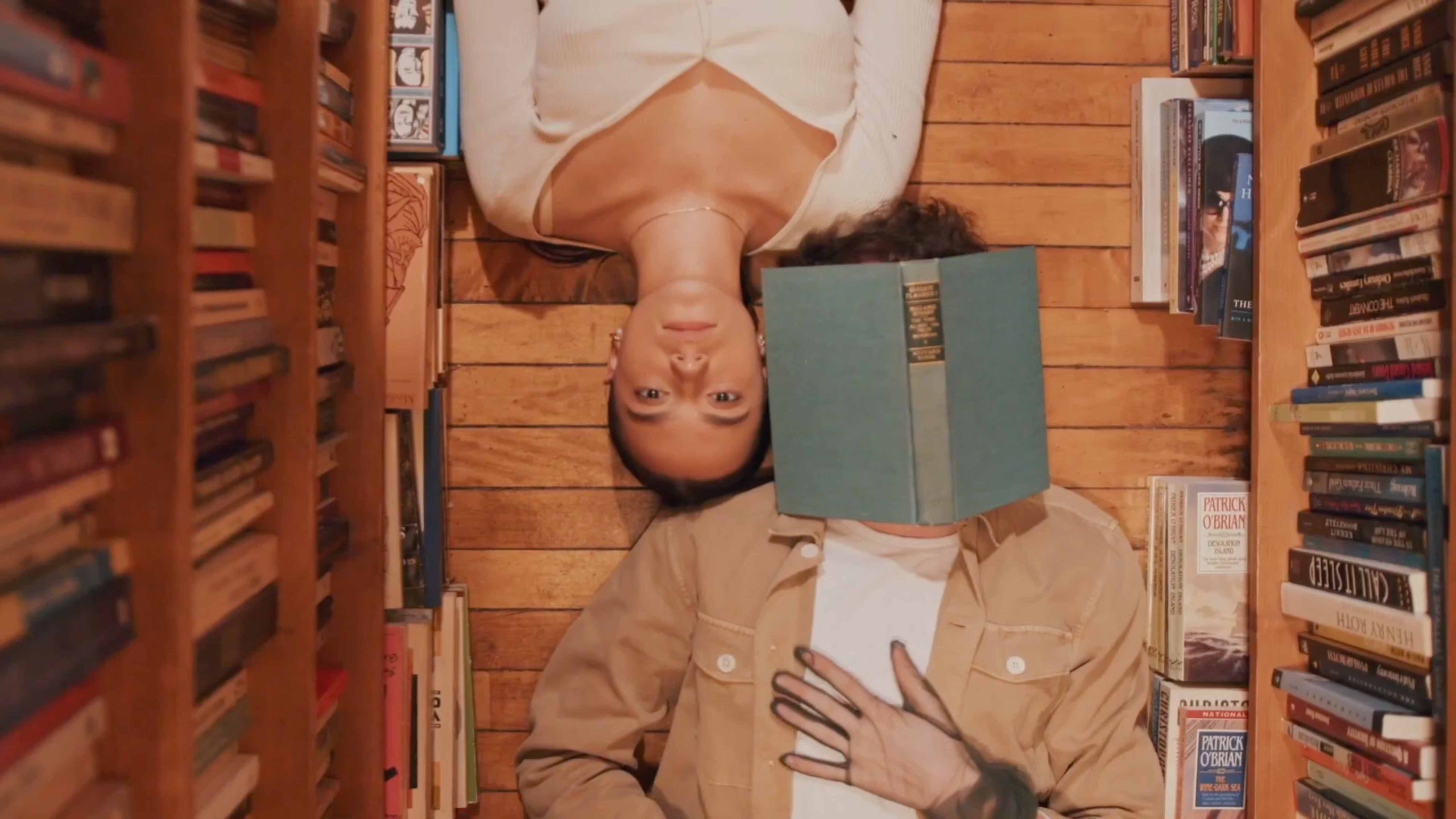

Blue Burrow by Leah O’Donnell

we/it end(s) here by Robert Farr-Jones

grave garden by ElleAnna Casterline

Although dance can be traced back to 9,000-year-old cave paintings, screendance is only as old as the technology that makes it possible – about a century. And it’s just in the last 20 to 30 years that this unique genre has become a niche field of dance.

Loosely defined as dance or choreography that is created with the express intention of being viewed on a screen or via a projector, screendance is known by many names: dance on camera, dance for camera, dance cinema, dance film, videodance, and more. It is distinct from the documenting of a dance work on film, in that screendance choreography is executed with an intentional relationship to the camera. As such, it is a hybrid art form that melds dance and film techniques.

This relative newcomer to the performing arts is now experiencing an explosive surge of popularity, at SMTD and around the world. The enthusiasm can be attributed to a confluence of factors: the limitless creative opportunities of the genre; ever more accessible technology, especially smartphones; a plethora of platforms for sharing video; and the pandemic-induced pivot to video and film by dancers and choreographers who were determined to continue making and sharing their art despite quarantines and lockdowns.

“The interest in screendance has always been high, but the pandemic created interest in a lot of people who maybe had never thought about it before,” said Assistant Professor Charli Brissey, who teaches the dance department’s screendance course. “Even faculty or classes that previously had nothing to do with screendance – everyone had to become proficient at it. And it started making people’s minds work in ways that they hadn’t before – they were suddenly looking at the effects of lighting, audio, camera angles, editing, and more.”

Even if their interest was to document a dance on film rather than create a screendance – artistic goals with big differences that Brissey strives to define in their class – many students turned to their cameras and discovered new creative possibilities. As a result, the screendance course, which can only accept 15–17 students per semester, now has a wait list that grows with each term.

“Because it’s a largely practice-based class and involves showing work and giving feedback to one another, we have to keep the enrollment fairly contained so everyone gets enough time with equipment and for feedback during project showings,” said Brissey.

To help accommodate the ever-growing interest in dance and film, the dance department recently added a second film course for the first time. “Dance Storytelling” is designed to provide students with a comprehensive understanding of field and film production fundamentals by employing the art of dance as a medium of conceptual storytelling. It teaches the principles of pre-production, production, and post-production that will support student efforts in either screendance or documentary filmmaking. Krisilyn “Toni” Frazier, a lecturer in the department, is the instructor.

Charli Brissey, assistant professor of dance, teaches the screendance course at SMTD.

New Spaces and New Technology Accommodate a Growing Interest

Fortunately, the heightened interest in screendance also coincided with last fall’s opening of SMTD’s new Dance Building, which includes the Dance Performance Studio Theatre, a multimedia performance space; and Studio 2, designed for the teaching, rehearsal, and production of screendance. Previously, the only studio on campus with the full apparatus for screendance – a sprung dance floor, lighting, camera operators, and greenscreen – was at the Duderstadt Center, and it was in constant and competitive demand. The new spaces are a panacea to dance students and faculty.

The Dance Performance Studio Theatre, with seating for 166, and Studio 2 will soon be equipped with all that’s needed for screendance.

“There’s a sense of relief,” said Brissey. “We can finally relax and not fight over spaces – it’s a breath of fresh air.”

The flexibility of the new screendance studio also provides the capability of transforming it, in as little as 20 minutes between classes, from a traditional dance studio to a screendance production studio or, by incorporating the 360-degree black curtain, to a black box theatre that can adapt to any type of performance.

Already in constant use, both studios will be completed this summer when they are fully outfitted with state-of-the-art technology and equipment, thanks to a generous gift from the Schwartzberg family. “Screendance is a critical form of dance,” the family stated, “and we felt it was important that the SMTD students (and future students) have the cutting-edge technology to allow them to express their creativity and talent. As with any athlete and creator, SMTD dancers need to have the proper equipment to maximize their creativity and their ability to impact the world with their work.”

“These studios are a real game-changer for what the department can do, or even imagine we can do,” said Brissey. “Pedagogically, it makes possible so much that we couldn’t do before and gives the students more of an understanding of what’s possible. Everyone is over-the-moon grateful and excited. I don’t know of any other college dance program that has as much in terms of technology infrastructure.”

Brissey points out that students will also reap bonus benefits from mastering the studio’s video technology: the ability to represent themselves professionally through media, whether creating a dance/choreographic reel, a video of themselves speaking, or a screendance. By demonstrating skills at editing, exporting files, and designing websites, job-seekers will have a leg up on their competition.

“Even if they don’t want to be filmmakers or screendance artists, having those technological chops will help them, regardless of what the job is or what their goals are,” said Brissey.

ElleAnna Casterline performs with projected video in her senior solo concert, grave garden. Photo credit: Kirk Donaldson.

ElleAnna Casterline, who just graduated in winter ’22 with a BFA in dance and BA in communication and media studies, said the new studios are contributing to exponential growth in the dance department.

“The old dance building did not have the technology, lighting, software, equipment, or space we have now,” said Casterline. “In the new building, I can project my screen work onto a stage-length cyc (cyclorama, or wall background stretched tight in an arc), connect my computer to studio TVs for sharing and editing purposes, rent camera equipment, and more. The new studio features have enabled me to fully investigate my opportunities as a pre-professional artist and opened me up to new endeavors and creations, such as my senior thesis video.”

Robert Farr-Jones, a sophomore dance major who is also pursuing a minor in performing arts management & entrepreneurship, is inspired by the new facilities and equipment.

“The large-scale projector has opened my eyes to possibilities of how screendance and traditional dance can interact,” he said. “I’ve now been brainstorming ways that I can incorporate screendance into my senior thesis, and perhaps a larger project as well. I also find, as a dancer who is extremely engaged in the choreographic process, screendance is one of many avenues that will develop my proficiency as a choreographer.”

The Origins of Screendance at SMTD

Professor Emeritus Peter Sparling, who established SMTD’s screendance course in 2000 with Terri Sarris, a lecturer at what was then LSA’s Department of Screen Arts & Culture, says the fully equipped new Studio 2 will have a tremendous impact on students.

“It will allow them to immediately immerse themselves in filming technologies such as greenscreen, multiple camera shoots, and the theatrical lighting specific to videotaping moving bodies,” he said. “These technologies in turn will allow for advanced use of editing effects. Given a home space in the Dance Building, students could advance significantly in one semester and then further hone their skills to create works for their senior concerts or MFA thesis work.”

When Sparling and Sarris first proposed a screendance course, they were anticipating the genre’s future growth and potential. “Terri and I both sensed an exciting trajectory for video as a new frame and lens for making movement art,” said Sparling, who later created a scholarship for the study of screendance.

Their initial proposal, funded by an Interdisciplinary Curricular Development Grant, was approved for just one year. But the course was an immediate success, attracting students from dance, visual arts, film/video, architecture, and a variety of LSA disciplines, so it was quickly renewed and became a permanent part of the dance curriculum. Sparling and Sarris, who co-taught the course, also curated and produced an annual screendance festival to expose U-M communities to the emerging hybrid form.

“The course became a broad survey of 20th-century art, incorporating aspects of the visual arts, dance, film, music, poetry, screenwriting, as well as various sociopolitical and identity studies,” said Sparling.

In the senior solo performance pictured here, Stephanie Gennusa, BFA ’22 (dance) and BA ’22 (psychology), used video to capture the live performance from a different angle, projecting the video onto the back wall of the venue. Credit: Sly Pup Productions.

That multidisciplinary aspect continues today, with the course enrolling many students from the Stamps School of Art & Design and LSA departments such as women’s and gender studies, which Brissey cites as a great enhancement to the course experience.

“The dance students are working with others who may not be dancers, but are thinking critically about technology and gender and race and surveillance; they bring this whole other perspective which is really helpful and amazing,” they said.

Viewing Both Dance and Film in a New Way

“Screendance is a new visual language for our time, and the impact is showing,” said Casterline. “With cultural and social commentary at the root of artistic expression, this engaging interdisciplinary practice is garnering the attention of new audiences and potentially reconstructing choreographic approaches.”

Farr-Jones is most excited about the possibilities that screendance presents. “This format gives me the opportunity to create even the most fantastical images that I see in my head, which couldn’t necessarily be recreated in a physical dance setting,” he said. “It’s an ever-intriguing game of exploring new methods of creation.”

“My mediums include site-specific dance, theatre, poetry, and festival,” said Marsae Lynette Mitchell, who will receive her MFA in dance this spring. “Screendance allows me to capture live performances and then edit them into new creative works, while also making the original performances more accessible.”

Accessibility is a key benefit of screendance, according to Leah O’Donnell, also graduating with her MFA this spring. She also points to the genre’s ability to extend the appreciation of dance in general. “Screendance introduces film audiences to forms of dance they might not otherwise seek, and it invites dance audiences to see the medium of film with new eyes,” she said. “Ultimately though, screendance is a category of its own. There’s a lot of room for interpretation and experimentation, and I’m excited to see what’s to come as many incredible artists continue to engage with the form.”