The Gershwin Initiative

A Unique Partnership

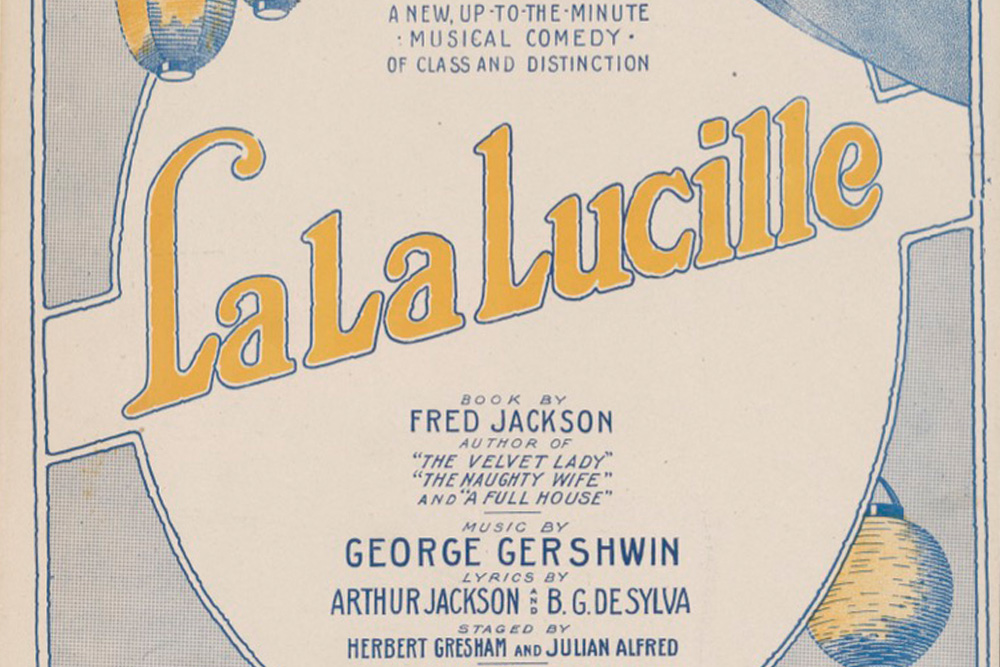

The University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance has entered into a long-term partnership with the Gershwin family to undertake a two-part initiative that will bring the music of George and Ira Gershwin to students, scholars, performers and audiences across campus and worldwide. The Gershwin Initiative includes 1) a new scholarly edition of George and Ira’s creative work, plus 2) educational opportunities for U-M students to perform and learn about the Gershwins’ art.

The George & Ira Gershwin Critical Edition

“Preserving the legacy and sharing the genius of both George and Ira Gershwin is a primary goal of creating a critical edition of their work. The University of Michigan, with research and performance disciplines that parallel the Gershwins’ music, will provide an ideal home for this project. We believe this partnership will help the art of George and Ira Gershwin take its place, for centuries to come, among the preeminent works of the 20th century and to spark the imagination of a new generation of musicians.”

– Marc George Gershwin, nephew of George and Ira Gershwin and majority member of the Marc George Gershwin LLC and trustee of the Arthur Gershwin Testamentary Trust

Media

Introducing: The Gershwin Initiative

Playlist: “Gershwin Centennial Celebration: Rhapsody in Blue at 100”

Gershwin’s An American in Paris: A New Two-Piano Arrangement

Rhapsody in Blue

Catfish Row Symphonic Suite

Rhapsody in Maize & Blue

Our Stories

Show Your Support

The Gershwin Operating Fund supports the initiative to bring the music of George and Ira Gershwin to students, scholars, performers and audiences across campus and worldwide.

Contact Us

Gershwin Initiative

attn. Andrew S. Kohler

Alfred and Jane Wolin Managing Editor

[email protected]

881 N. University Ave.

602 Burton Memorial Tower

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, MI 49104-1270