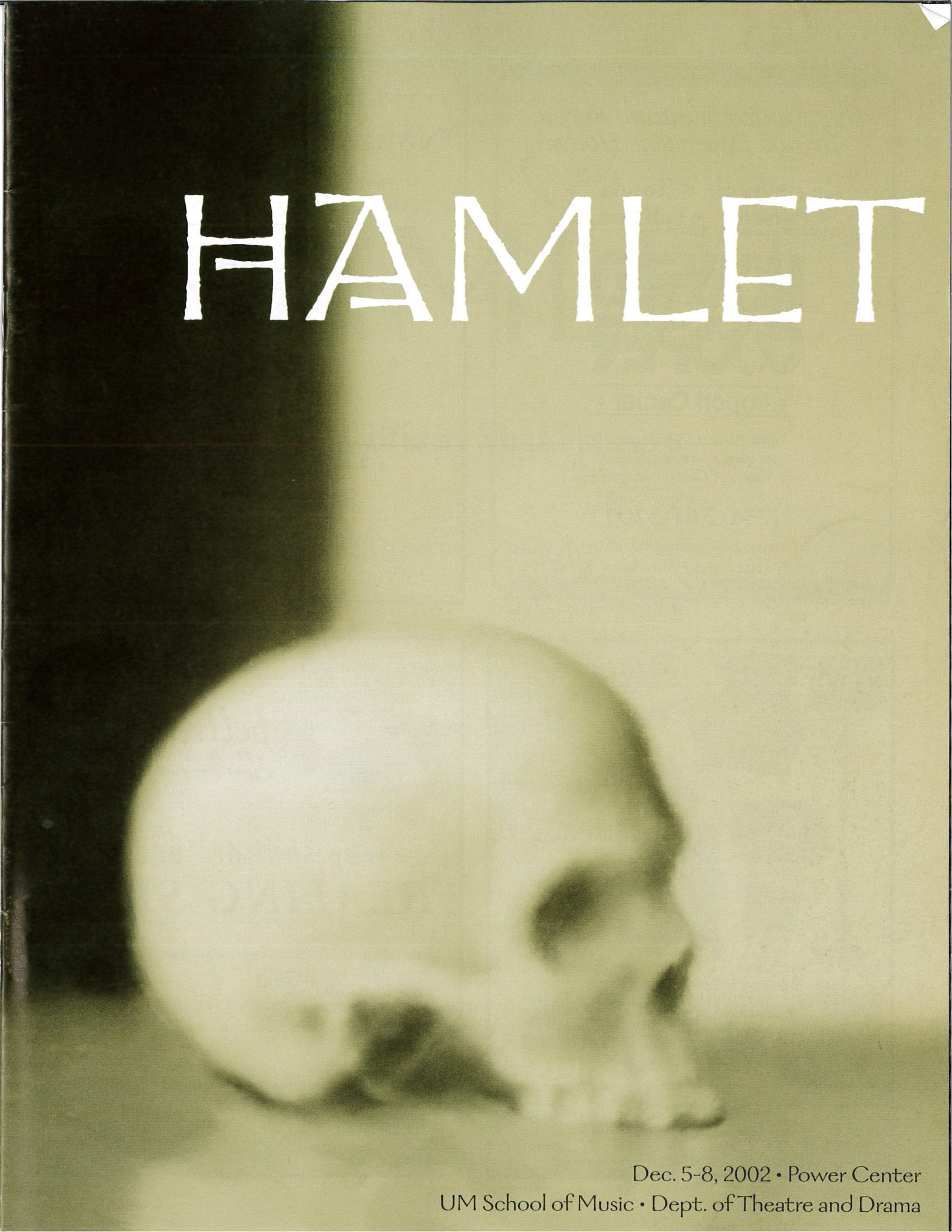

Hamlet

By William Shakespeare

Department of Theatre & Drama

December 5-8, 2002 • Power Center

Artistic Staff

Director: Philip Kerr

Consulting Director: Mark Lamos

Assistant Director: Sarah-Jane Gwillim

Scenic Designer: Vincent Mountain

Costume Designer: Christianne Myers

Lighting Designer: Rob Murphy

Sound Designer: Jim Lillie

Fight Choreographer: Erik Fredricksen

Stage Manager: Blair Preiser

Cast

Hamlet, Prince of Denmark: David Jones

Claudius, King of Denmark, Hamlet’s uncle: Anthony E. Cantrell

Gertrude, the Queen, Hamlet’s mother, now wife of Claudius: Elizabeth Hoyt

Polonius, Councillor of State: Dan Granke

Laertes, Polonius’s son: Brad Fraizer

Ophelia, Polonius’s daughter: Audra Ewing

Horatio, friend of Hamlet: Nnamudi Amobi

Rosencrantz, former schoolfellow of Hamlet: Jason Smith

Guildenstern, former schoolfellow of Hamlet: Joshua Lefkowitz

Osric, aide to Claudius: Jonathan Rosen

Reynaldo, aide to Polonius: Zachary B. Dorff

Marcellus, officer: Ethan B. Kogan

Bernardo, officer: Edmund Alyn Jones

Isabella, court lady: Joanna Fetter

A Priest: Adam Miller-Batteau

A Grave-Digger: Aubrey Levy

Player with cello: Lauren Molina

Young Player guide: Henry Mountain

Young Player drummer: Julian Mountain

Young Player with recorder: Sophie Tulip

Old Player: Philip Kerr

Head Player: Christina Reynolds

Player from Germany: Evan Bryant

Player from Russia: Holly Maples

Player from Italy: Julie Strassel

Player from France: Karenanna Creps

Player from Greece: Joanna Spanos

Player from Tibet: Michelle Alizabeth Roberts

Player from Malaysia: Maureen Sebastian

Swings: Brian Luskey, Sean Ward

Sponsors

The School of Music acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Resources

Director’s Notes

This production marks my fourth encounter with Shakespeare’s tragedy, my first having occurred some years ago as an actor in the title role. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have first met the play as a participant inside its great and complex mechanisms, for it is very much a play about the process of acting and the meaning and potential of theatre, both as an art form and as an act of intent. The role of Hamlet tends to wrap itself around any actor who plays it; it gives one a sense of liberation, probably because it utilizes so many aspects of the actor’s personality, as well as the currents of one’s personal life at the time he comes to play it. And though the role is a consummate challenge, most actors understand the part with an immediacy that is uncanny. This, too, probably has to do with the fact that so much of the play is about the art of acting. Almost every character in Hamlet is involved in the act of role-playing, and Hamlet himself spends most of his time, like any actor, attempting to understand motivation and meaning. And then there’s the great center of Hamlet: the play-within-the-play, a piece of theater whose mission is to reveal the truth (the goal of all art) and to change the course of events, which (unlike most works of art), it most emphatically does.

Though he may be daunted by the prospect of facing up to a tradition older than his own time, the actor playing Hamlet is also encouraged by the role to take risks and make statements about his art form – in this way, playing Hamlet is probably the closest thing we have in Western Theater to the performance traditions of the great Kabuki actors of Japan, who refine and bring personal nuance to parts that have been played for centuries. It’s also similar to great roles in opera and ballet perennials.

The drama of Hamlet is about performance, playing, pretending, and by extension, interpretation – the discovery of meaning. It is about using illusion in order to strip illusion and expose truth.

Because Shakespeare updated an older play to his own time, Hamlet‘s first performance was itself an interpretation, a comment on another play. The hero’s very first line, “A little more than kin and less than kind,” is in fact a direct steal from the old play, as are characters and plot developments. Perhaps this is the main reason why Hamlet always seems to be a play of our time, whether we’re 19th-century Romantics, early Freudians, ’60s drop-outs, ’80s existentialists living with AIDS, or 21st-century students facing the unknown horrors of terrorism and war. Claudius can represent all of our lying, opportunistic leaders, and Gertrude, all of our complex feelings about the mother who brought us into this world.

The play is about watching. One of Shakespeare’s most constantly explored themes is the interaction of audience and actor. In play after play, comedy or history or tragedy, this most experimental of playwrights was forever concerned with truth and illusion, acting, pretending, perceiving. In Philip Kerr’s production the arrival of the Players signals a change in the atmosphere of the claustrophobic, lust-filled, secretive world of Elsinore. The actors here are instruments of change, embraced by Hamlet, who seems to trust the power of the actor to reveal the truth more than he trusts the words of his ghostly father. The highly educated, skeptical Hamlet wonders if, after all, the vengeful ghost was only an illusion. Afraid to act without more empirical facts at his disposal, he plans another illusion – a play – deciding that “The play’s the thing wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.”

The concepts of Acting – and Theater – as forces of change are a young man’s fantasy, unfortunately “a consummation devoutly to be wished.” But while Hamlet holds the stage, the truth of that concept seems thrillingly undeniable.

– Mark Lamos, Consulting Director