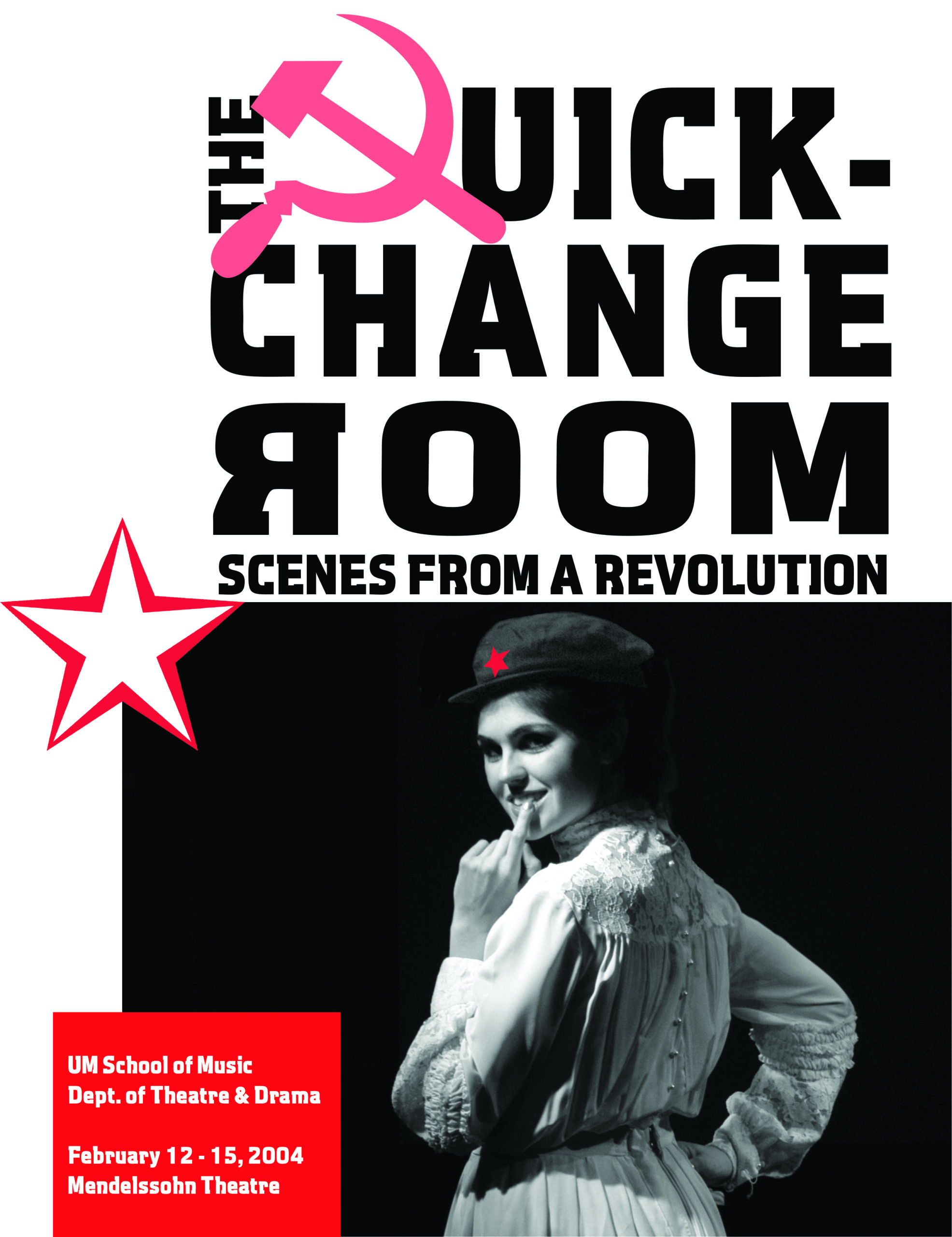

The Quick-Change Room

Scenes from a Revolution

By Nagle Jackson

Department of Theatre & Drama

February 12-15, 2004 • Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre

A powerful and hilarious comedy of the struggle between artistic integrity and commercial viability during the disintegration of the Soviet Union, The Quick-Change Room is the final stage presentation of U-M’s “Celebrating St. Petersburg” festival, a University-wide festival commemorating the 300th anniversary of a city that has been extraordinarily influential on Western culture.

The story is set in the state-run Kuzlov Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia. In the waning days of the Soviet communist regime, the theatre is having hard times – its audience is shrinking, the leading lady is past her prime, and they don’t even have soap. But a new production of The Three Sisters will surely turn things around. As the theatre and its denizens cope with the changes brought about by perestroika, even Chekhov’s masterpiece isn’t safe from the ravages of capitalism as it becomes an American style musical titled O My Sister! The quick-change room of the Kuzlov, the small backstage room where dressers provide the fast costume changes necessary during a play’s action, serves as a microcosm for the “quick changes” in the economic, moral and philosophical systems of Russia brought about by the downfall of communism.

Artistic Staff

Director: Philip Kerr

Assistant Director: Sarah-Jane Gwillim

Scenic & Lighting Designer: Gary Decker

Costume Designer: Sheila McClear

Sound Designer: Christopher Konovaliv

Choreographer: Garrett Miller

Stage Manager: Erin A. Whipkey

Cast

Nina, a student actress: JoAnna Spanos

Marya Stepanova, wardrobe mistress/supervisor: Erin Farrell

Lena, seamstress and dresser: Elizabeth Hoyt

Sergey Sergeyevich Tarpin, Director of the Kuzlov Theater: Adam H. Caplan

Vera, his assistant: Sari Goldberg

Nikolai, an actor: Brad Fraizer

Ludmilla Nevchenka, prima donna actress: Anika Habermas-Scher

Anna, leading actress: Meghan Powe

Boris, box office manager and procurer: Brian Luskey

Sasha, stage electrician: J. Theo Klose

Tatyana, an actress: Allison Brown

Svetlana, an actress: Kellie Matteson

Timofey, stage hand: Zachary Booth

Itap, stage hand: Justin Patrick Holmes

Sponsors

The School of Music acknowledges the generosity of McKinley Associates, Inc. whose support has helped make this production possible.

Resources

Notes from the Russian Front

In the spring of 1986, I was invited by the director of the Bolshoi Dramatic Theater of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), known as the Gorky, to direct a production there. In exchange, Georgi Tovstonogov, the theatre’s Artistic Director, would come to the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey, of which I was Artistic Director, to stage his celebrated production of Chekov’s Uncle Vanya. It was the first private cultural exchange between the Soviet Union and the United States; that is, it was not arranged officially between government agencies. It was one of the first cultural fissures in what would become the earthquake called “perestroika.” For Georgi and me, however, it was just a deal we made over lunch at Sardi’s! There have since been countless such “deals.” My superb colleague and friend, Mark Lamos, then heading up his splendid Hartford Stage Company, was invited a year later to stage Desire Under The Elms in Moscow; as it turned out, we both arrived in Russia around the same time: March-April of 1988. Mark’s production opened a few weeks before my staging of The Glass Menagerie. (Georgi asked me over a transatlantic phone call – rare from the USSR in those days – if I would be interested in staging “that Williams play about the zoo.”) This, then, is the background behind my writing The Quick-Change Room.

The usual disclaimer – “any resemblance to persons living or dead, etc.” – almost holds. Certainly “Sergey” reminds me of Georgi, but without the real director’s robust Georgian temperament. And there was a Boris, but he was scarcely the Machiavellian we meet in my play; he was my guardian angel, a true factotum who could “arrange” anything. And, no, no one suggested that we should turn Tennessee William’s gorgeous play into a musical.

It was a fascinating time to be in Russia; heady optimism was in the air. People nearly said what they wanted and the fact that the phone in my apartment (located in the theater) was bugged didn’t worry me in the least. But a cynical side of my nature kept asking: “Do they know what they’re getting into?” I could see what would happen to this theatre company, which employed some 300 souls, when government subsidies vanished to be replaced by box office reality. No one could remember ever having seen an empty seat in the theater’s 1500 seat auditorium. Eight shows a week, a repertory of some twenty to thirty plays and tickets priced at the equivalent of about two dollars – this was the happy state of affairs then. Now, of course, that has all changed (although my production of The Glass Menagerie is still in the repertory!). Tickets cost a lot more than two dollars. I have written a comedy because that is all I know how to do. But beneath the sometimes farcical energy there is deep concern. This play is a tribute and a gesture of great love to the wonderful Russian artists I was privileged to work with. I hope you will share my affection for them.

— Nagle Jackson

I met Nagle Jackson when I was in Moscow in 1988 directing the Pushkin Theater Company in a production of O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms (Lyubov pod Viasami). By a diplomatic hair’s breadth, I became the first American director to work with a Russian theater company in the “former Soviet Union;” Nagle’s The Glass Menagerie opened a few weeks later in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg; but we were rehearsing at virtually the same moment. I couldn’t get away from Moscow, so Nagle took the train from St. Petersburg, and we spent a happy, chatty day together, having our picture taken in front of the Kremlin, both of us gushing with relief at finally being able to communicate without an interpreter! We shared impressions of our curious time in Russia and traded tales from the trenches of Regional Theater Land back in the States, since both of us were artistic directors in those days. It was a thrilling time for us, and for the West. Russia was experiencing “perestroika,” and every day brought new sights to the weary eyes of Russians who had lived under the repressive regimes of the last fifty years.

Rehearsals for the O’Neill were fascinating and frustrating in equal measure. I had wondered why the artistic director was so set on having me direct the O’Neill tragedy. Deep into rehearsal, I circuitously discovered the reason, and it was a melancholy one. O’Neill himself had supervised the Russian premiere of the play on this very stage, directed by Pushkin founder Alexander Tairov. Pictures of the production were astonishing – highly abstract, Expressionistic, like a mad dream – as far from realism as you could imagine. Clearly, I thought, looking at the photos, these were groundbreaking artists, and, tragically, they were tortured and assassinated in one of Stalin’s camps. My production was a fist raised in defiance as a reminder of a not-too-distant Russian past in which artists were murdered because of race, beliefs, and artistry. Suddenly, O’Neill’s play became more important to me than ever, and I realized why the actors were so committed to bringing it to life.

I had to leave my own country and go to Russia to make theater that was a political act. For me personally, this was a big step. I think about it now in relation to our upcoming An Arthur Miller Celebration (April 2 – 11 at the Trueblood Theatre.) Arthur Miller was almost the only American playwright whose artistic vision could be even remotely perceived as political – theater about ethics, morals, political movements, the consequences of history – among much else, of course. Arthur has spent a great deal of his long life actively fighting the oppression of artists around the world, most particularly in the once-Communist countries, where dissident artists, authors, actors, etc., simply “disappeared” and were never seen again. Not until Solzhenytsin’s horrific Gulag Archipelago in the 1970s, did the world begin to comprehend the extent of murder and oppression that was finally disappearing as Nagle and I rehearsed our American plays with spiritually-starved but newly-empowered Russian actors and artists.

— Mark Lamos